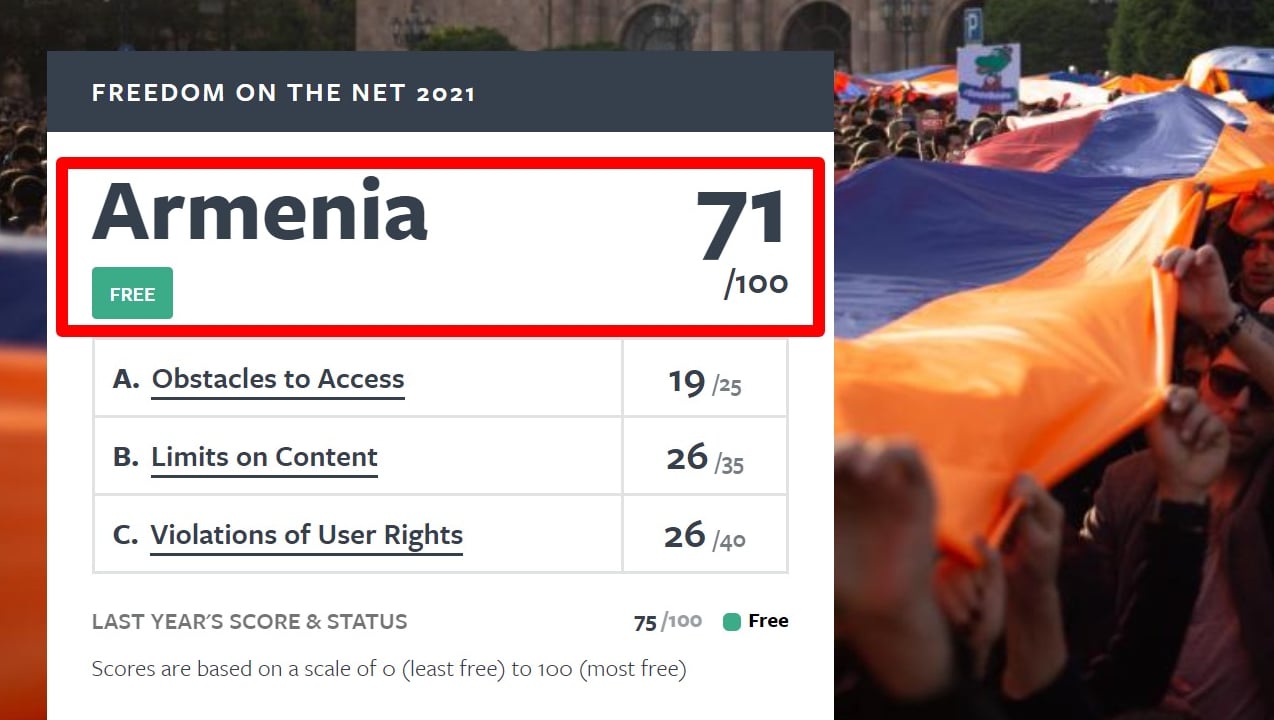

The human rights organization Freedom House has published the “Internet Freedom 2021” report, where it has studied the internet landscape of 70 countries around the world. Armenia was considered free with 71 points (out of a maximum of 100). This is lower than the figure from last year (75).

Internet access, access barriers, content restrictions, and violations of users’ rights were monitored.

Armenia and Georgia are among the free countries of the South Caucasus, and Azerbaijan is among the non-free countries. Russia, Belarus, Turkey and Ukraine were also considered not free.

In the case of Armenia, the Karabakh War and martial law were taken into account, which had a significant impact, creating leverage for restrictions. The authorities demanded the removal of the content and imposed fines.

The measurement of Internet freedom also included the quality of reforms and the ability of political forces to intervene in the media field and in the judiciary. Despite the promised reforms, there is a great danger that this intervention will be maintained.

Barrier to entry

Internet access is easy in Armenia. In Yerevan, the Internet is available almost everywhere – in public places, schools, universities, transport, etc. This tendency is spreading in other regions as well.

According to a 2020 study by the World Bank, 96% of households in Armenia have access to the Internet. In addition, 4G+ technology is widely used for mobile networks (the issue of introducing a 5G network is delayed). Moreover, the speed of mobile internet has decreased during the observed period, and the speed of broadband internet has increased.

The fact that during the epidemic, many educational institutions and organizations worked online, and the Internet was a necessary tool was taken into account. During this period, Internet providers (there are four in Armenia) have noticed a 15-25% increase in Internet usage, traffic.

Internet connection prices in Armenia are relatively affordable, though there has been a slight increase in prices. And in the days of the epidemic, Internet providers provided free and uncontrolled access for educational institutions to hold classes and video conferences.

As of January 2021, all 1003 localities in Armenia were covered by a 4G+ mobile network.

Access was restricted when TikTok was not available for several weeks during the 44-day war, although the authorities did not confirm that it was voluntary. Instead, the RA ombudsman spoke, calling on children to refrain from content containing violence during the war.

The quality of the Internet was reduced in February 2021, when there were political upheavals, but neither the authorities nor the Internet providers officially confirmed it.

The Freedom House report states that there are no significant restrictions on access to the telecommunications market. There is no need for a license anymore, the service provider simply informs the PSRC (it is another matter that this body was previously known for its corrupt activities).

According to the latest data, there are 183 providers in Armenia. But three operators control almost the entire fixed broadband market. In the first quarter of 2021, Ucom had 150,647 subscribers, Beeline – 55,127, Rostelecom – 58,493. This information was provided by the suppliers.

Content restrictions

Overall, content protected by international human rights standards is not blocked in Armenia. However, during the war, the freedom of the Internet was significantly reduced.

A negative factor was the unavailability of the TikTok social network and a number of websites operating in the az and tr domains. Those sites were also unavailable after the ceasefire.

Some local websites were attacked by DDoS (mostly from Azerbaijan) and were also temporarily unavailable during the conflict.

These were the negative factors, and the positive one is that the provision of data collected from the citizens of the Republic of Armenia during the coronavirus epidemic was canceled by the government. In other words, the telecommunication companies were no longer obliged to share information about their subscribers and their location with the authorities.

During martial law, the authorities were given the opportunity to demand the removal of articles and posts from individuals in the media and to impose fines if that did not happen.

As of November 9, authorities had reported 401 blocked posts, of which 196 were media content and 205 were social media content.

Thirteen news websites, whose names were not released to the public by the police, were fined 700,000 AMD ($1,430). In one publication, the author of which refused to remove it, the author was fined an additional 1.5 million AMD ($3,000).

Content restrictions were in place before the war. They were connected with the state of emergency caused by the pandemic.

By March 23, 2020, authorities had contacted 22 media outlets asking them to edit or remove “non-official information.” The point of those demands was later removed.

“The online information field in Armenia is polarized, subject to political pressure, and full of misinformation. In some online media, journalists are not allowed to deviate from the editorial policy of their employers, which often depends on political parties or forces,” the report said (one example being Haykakan Zhamanak).

Two crises, the war and the pandemic, contributed to the growth of misinformation and misleading information. The audience became more vulnerable.

One of the main sources of misinformation in Armenia is the media and individuals who belong to political-ideological groups or are related to the Russian media field. Far-right forces also spread misinformation from their social media accounts (mainly Facebook and YouTube) and their friendly websites.

The Armenian-Azerbaijani war left its mark on social networks, where accounts were blocked. There were cases when network administrators viewed posts as hate speech or false information without sufficient grounds.

Both the ruling and former authorities have been accused of using fake accounts on social networks. For example, My Step and the PAP.

In February 2021, Twitter removed 35 accounts linked to the Armenian government. These accounts were created to promote content targeted at Azerbaijan. In some cases, the false accounts were presented as political organizations and media organizations residing in Azerbaijan. Most of these accounts have been operating since 2016, the war made them more visible.

There is a point in the Freedom House report that is more favorable for internet freedom. It is the absence of economic restrictions.

Economic levers are not used in Armenia to restrict the right to free expression. There are some regulatory mechanisms in the field of surface broadcasters. And the advertising market is small but more liberal than it was before 2018. Online commerce has also developed.

According to experts, in 2018 the online advertising market was $3.5 million, and most of the streams went to bookmakers.

The Internet is the main source of information for Armenians (36.5%), and the issue of reliability is important. During the Armenia-Azerbaijan war, the Armenian government kept the frontline information secret, promoting misinformation and reducing public confidence in official sources.

Violations of users’ rights

The violations of rights are connected with the judicial system, the reform of which did not take place. The court is considered the least reliable institution.

The Constitution of the Republic of Armenia guarantees the freedom of speech of individuals and the media, the criminal legislation also gives certain protection to journalists. However, no law clearly defines who a journalist is (say, an online employee or a blogger). And the defense sounds problematic.

Recently, several restrictive laws and legislative acts have been adopted in Armenia.

Due to martial law, content that “criticizes” or “denies” the actions of officials related to national security was banned. A clause was added to the law criminalizing publications that “question the effectiveness of those actions or devalue them in any way.” In fact, this restriction lasted until March 2021.

Moreover, parliament passed tougher sanctions for defamation, although defamation was decriminalized in 2010, and in 2011 the Constitutional Court ruled that courts should avoid imposing heavy fines on the media for defamation.

In July 2021, the parliament passed a law punishing severe insults or swearing at civil servants, politicians and other public figures with a fine of up to 500,000 AMD. In case of recidivism, the fines can reach 3 million AMD and up to three months of imprisonment.

According to this provision, no criminal cases have been initiated, but the change contains a danger that it will have a negative impact on freedom of speech and is not realistic. Especially taking into account the fact that insults and curses are heard from the highest tribunes.

The laws on pornography and copyright are in line with international law.

In Armenia, the downloading of illegal or copyrighted material is not prosecuted until the prosecutor’s office has proven that the content was stored with the intention of distributing it.

In the Freedom House report, Armenia also ranks lower because of the increasing number of people being punished for their online speeches. Or they are arrested without sufficient evidence. Calls for violence or hostile remarks often do not end with a valid accusation.

Physical violence against journalists and individuals in connection with their publications has decreased since the Velvet Revolution but has not disappeared. In 2020, the Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression registered 4 cases of physical attacks on journalists in Armenia and 2 cases in the Artsakh city of Martuni due to Azerbaijani shelling.

Hate speech against LGBT+ people continues to be frequent. It is mainly spread by far-right organizations and political movements.

In December 2020, the Human Rights Defenders of Artsakh and Armenia published a joint report on hate speech from the Azerbaijani and Turkish media. The report said that Facebook, Twitter and TikTok were calling for the destruction of heritage sites through violence, murder, torture and inhumane treatment.

Nune Hakhverdyan

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.