There is a cemented stereotype that Western journalism is the highest level and there is nothing beyond it. The Second Artsakh War revealed, at least for me, the poverty and misery of “Western Journalism” in a number of important issues, its ethical bankruptcy.

Representatives of one of the famous British periodicals came to Armenia during the first days. The Armenian fixer working with the group (whose name and the name of the periodical I will not publish at the latter’s request) spoke to me about a case that is incomprehensible and unacceptable to an Armenian during a meeting with me after working with the group.

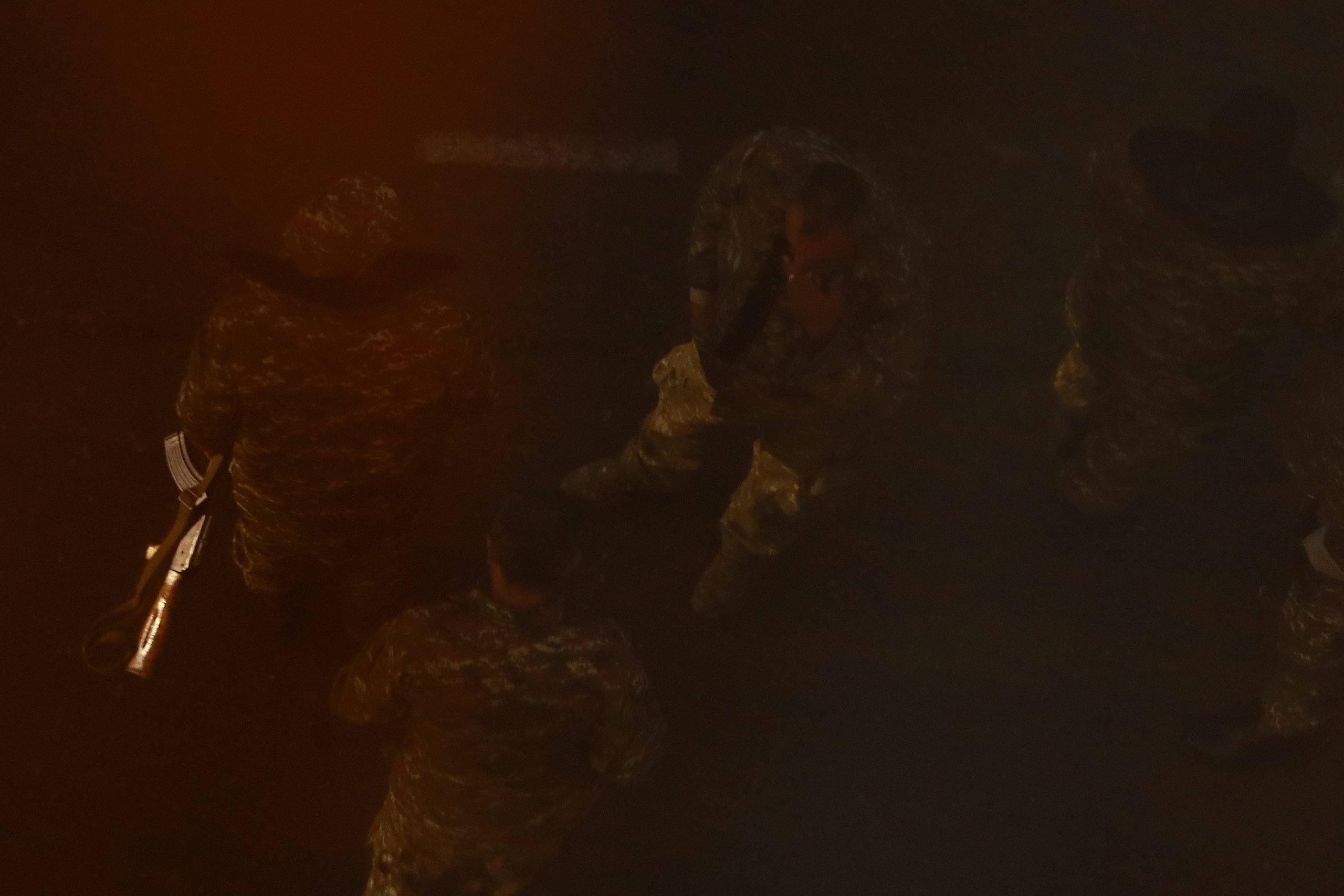

Armenian volunteers near Goris

The House of Culture in Shushi was destroyed as a result of a rocket attack, and many of those inside had died. The bodies of the victims were taken out, my interlocutor bumped into an acquaintance there, whose relative was also among the dead. They hugged, tried to comfort each other. The English journalist hurried to intervene and understand whether the man with tears in his eyes was ready to give an interview or comment.

“I had to take him aside, I tried to explain [to the British journalist] that there are times where not everything should be done so quickly. How can you explain something like that to a person? Let the other person calm down, dear, do you understand? He [the victim’s friend] came and hugged me because he had finally seen a familiar face, he wanted to let out what he was feeling inside,” my interlocutor confessed.

There were journalists of several foreign media outlets, including Russian periodicals, in the car going to Artsakh. Just as it is typical of Russia, which has historically chosen only its “special way,” so Russian journalism is an incomprehensible hybrid of professional journalism and the state propaganda machine. Those who are more or less separate from the state propaganda machine have an inner confidence that they are unique. In fact, these are different polar approaches to Armenian reality. Writing about objective reality is courage for Russian journalism, but an everyday occurrence in Armenia. Ilya Azar (he wrote for Новая Газета about the war in Artsakh) has a controversial reputation in Russia, but his long texts are in high demand. In Armenia and Artsakh he was looking for special heroes, unique heroes, and one day he found them. The main point of his extensive texts was often people whose thoughts were about misconceptions. Like any journalist, I know a rule: if I want to find or talk to a specialist, I must find a competent representative in this or that field. He said that the situation in the Arabian Peninsula should be commented on by either a diplomat who worked there at the time, or an Arab scholar, or a political scientist who specializes in political events in the Arab world. Ilya Azar often does not have such a logic. It does not make sense to rewrite his extensive texts, but he did not seem to admit the shortcomings of his own work, even in debates with his Russian colleagues. He did not accept why the RA Ministry of Foreign Affairs deprived him of his credentials. And the main jewel he had reserved for what he had done in the matter of armor and helmet. It seems that it is about personal security, but the explanation was more than telling․ “Well, I thought everything would be as light as it was in 2016 [we are talking about the four-day war], that’s why I thought there was no point in dragging more cargo with me.”

A car damaged by a rocket attack in Stepanakert

In general, Armenian journalists-photojournalists understand that whatever you write and what you publish from the front line, will make you responsible for everything that will happen in the future. That perception is present in almost all of us. I repeat, almost everyone and if there are accidental shortcomings, it is justified by objective and subjective circumstances. For the representatives of journalism in the Western world, the sense of responsibility is minimal. It is instructed not to film targeted buildings or an entire area․ It can reveal whether the missile has hit its target or not. For Western journalists, such an instruction seems to mean the exact opposite․ “To film that very building, to film it exactly as they are asking us not to film it and in general, because it is a war, to work however you want…” The logic is the same, if you are asked not to film, then there is some interesting and extraordinary topic.

In the car transporting us to Artsakh, the employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs asked us,

“Gevorg dear, of course I have warned them, but if you notice that military vehicles on the road are taking pictures, tell them not to take pictures․․․”

The Azerbaijani army shells the road from Lachin to Berdzor

Armenian journalists on foreign business trips also go, but it seems that the demands placed on Armenian journalists abroad and on foreign journalists are categorically different. Working in hotspots also requires special work. It is not just a football match and summit, where you come with a clearly defined route, work with a clear agenda. Moreover, all the hotspots differ from each other in that they are in conflict. The way the military talks to a journalist in Donbas is different from how they will communicate with a foreign journalist in Artsakh.

“I’m surprised, you know, Gevorg, I have received almost no rejection during my work here. Everyone agrees to talk and share with you. They even help while you work,” the BBC employee confessed, adding that he had not seen such a lack of rejections anywhere else.

Armenian volunteers leave for Artsakh

Like any ordinary Armenian journalist, I have participated in a number of seminars, attended meetings with well-known representatives of Western journalism, and now it is time to think about an issue. It may be worthwhile to start a training seminar in Armenia for the new generation of journalists in the Western world on “Journalistic Ethics in Conflict Zones.”

Gevorg Ghazaryan

Photojournalist, Xinhua

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.