At the beginning of the Karabakh movement in 1988, Armenian official newspapers followed the same information policy established during the Soviet era. They were unable and unwilling to report on the movement’s progress or present perspectives that differed from the state party’s stance.

During that period, some newspapers were more independent and bold, known as self-published press or “samizdat.” These newspapers typically lacked a defined external design and were composed of typewritten pages duplicated and bound together. The primary purpose of these newspapers was to spread the ideas of different political forces or parties, essentially serving as a platform for publicity. In addition to this, these newspapers also included unique event descriptions and information that other newspapers did not cover. Self-published newspapers had a structure similar to that of regular newspapers. They usually had separate titles and sub-titles, with the most significant being the open editorials. Open editorials were called “Editorials” or “commentary articles,” depending on the newspaper. They represented the newspaper’s interpretation and analysis of the most important event happening at that moment. Sometimes, they also contained appeals to the public.

On September 29, 1988, the Armenian parties of the Diaspora, including ARF (Armenian Revolutionary Federation), ADl (Armenian Democratic Liberal Party), and SDHP (Social Democrat Hunchakian Party), released a joint statement. In the statement, they urged the authorities of Soviet Armenia to be more forceful and better address the people’s legitimate demands.In another statement, the parties strongly condemned the National Movement, rallies, and strikes. According to the statement’s authors, such actions harm relations with Soviet authorities and other republics. They stated, “These actions will serve the ulterior motives of the enemies of our people.”[1]։

In Armenian political circles, the statements made by diaspora parties, particularly Dashnaktsutyun, were received with severe criticism. In 1988, the National Self-Determination Association’s self-published newspaper, “Hayrenik,” dedicated an entire op-ed in its September issue to this statement. The author was Hakobjan Tadevosyan, a former Soviet dissident and a Union of Armenian Patriots member. In his commentary, Tadevosyan strongly criticized all political parties, especially the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, for their opposition to the National Movement and support for the Soviet authorities.

The open editorial of “Hayrenik” newspaper made extensive references to history, which was intertwined with the ongoing events. The op-ed discussed the main symbol of Armenian statehood, the tricolor (flag). It drew parallels with the events of the First Republic period, the Soviet disciplinary practices, and the national movement against Bolshevik violence in February 1921. Hakobjan Tadevosyan wrote about the Armenian people’s struggles for independence in his “The Scream of the Tricolor” column. He quoted the outcast Dro (Drastamat Kanayan), “Out of every three Armenians, if truly Armenian, three have been imprisoned so that one day they will see the light of the sun and flourish in their homeland.” Tadevosyan then went on to describe the events of the Karabakh Movement of May 28, 1988, “And that was the result of the unprecedented national struggle, where all our imperfect national desires united under the name “Karabakh movement” awakening the best elements of the nation.”[3]։

The open editorial of “Hayrenik” newspaper made extensive references to history, which was intertwined with the ongoing events. The op-ed discussed the main symbol of Armenian statehood, the tricolor (flag). It drew parallels with the events of the First Republic period, the Soviet disciplinary practices, and the national movement against Bolshevik violence in February 1921. Hakobjan Tadevosyan wrote about the Armenian people’s struggles for independence in his “The Scream of the Tricolor” column. He quoted the outcast Dro (Drastamat Kanayan), “Out of every three Armenians, if truly Armenian, three have been imprisoned so that one day they will see the light of the sun and flourish in their homeland.” Tadevosyan then went on to describe the events of the Karabakh Movement of May 28, 1988, “And that was the result of the unprecedented national struggle, where all our imperfect national desires united under the name “Karabakh movement” awakening the best elements of the nation.”[3]։

In the late 1980s, the first self-published newspaper in Soviet Armenia was the “Ankakhutyun” newspaper of the Union of National Self-determination (USD), established in October 1987. Initially, the newspaper mainly presented the views of the organization and its leader, Paruyr Hayrikyan, such as various public appeals, the USD’s provisions, and the path to Armenia’s independence. Over time, the newspaper gradually increased the number of pages and titles. In addition to the above-mentioned issues, the newspaper addressed Armenian-Azerbaijani and Armenian-Russian relations, as well as published local and foreign “forbidden” news.

In 1988, the “Ankakhutyun” newspaper published its 15th issue on April 11. This issue was the first to include an Op-ed; the article centered around the details of Paruyr Hayrikyan’s arrest. The article was signed with the initials “R.H.,” who is believed to be Rafael Hambardzumyan, a USD member.

It was common for the “Ankakhutyun” newspaper to feature a leading article in each issue, but they did not consistently include a separate section entitled “Editorial.” Although issues 29 and 30 had this section, it was absent in many later issues. Upon observation, it appears that the “Editorial” heading contained articles mainly related to the arrest of Paruyr Hayrikyan and USD’s main political direction towards independence. These articles discussed general politics, as opposed to columns without a headline, which focused on specific events.

In 1991, irreconcilable differences emerged between the USD and the newly formed RA government. Disagreements were not only published in interviews and reviews but also took the form of open editorials. On June 28, 1991, “Ankakhutyun” warned that the authorities were on the verge of disintegration due to the increasing powers of the Supreme Council. “The project to create a new presidency or to endow the existing one with additional powers was nothing but an attempt to reestablish the Soviet tyrannical system in Armenia; it was rejected, despite Mr. Ter-Petrosyan and his supporters sparing no effort to accept it,” the newspaper wrote.

The “Mashtots” newspaper, published by the “Goyapakar” youth union, featured editorials with a national direction. It fought for the preservation of the Armenian language and promoted educating children in Armenian schools, which was a popular movement at that time. The newspaper also addressed environmental and political issues. Under the heading “Editorial,” the newspaper published significant national news. In 1989, the May issue of “Mashtots” was dedicated to May 28, the founding of the First Republic. Since 1989, May 28 has been celebrated as the Republic Day.

The newspaper wrote, “Soviet Armenia exists today due to the establishment of the new Armenian statehood and its survival for two and a half years. The presentation of the history of the Armenian Republic to the people will reinforce the nation-state thinking of the Armenian population; this is why May 28 has become the most significant national holiday of the Armenian people.

Between 1988 and 1990, Armenian newspapers followed the same working style of expressing the state’s point of view and evaluating events from the state’s perspective. However, in 1990, there was a noticeable shift in the content of the newspapers. They began addressing national issues more frequently. This change became more evident after the second round of the Supreme Council elections and the new government’s formation in July 1990. The narratives of the official press changed completely, and it marked the beginning of the formation of the new press of independent Armenia.

The official newspapers of traditional Armenian parties, which began publishing in the homeland in 1991, played a significant role in establishing the press in newly independent Armenia.

In February 1991, the official newspaper of the Ramkavar Liberation Party, called “Azg,” started publishing in Yerevan and quickly became a leading press outlet in Armenia. The newspaper featured a new structure, content division, and an open editorial section, which provided readers with important reactions and opinions on internal political developments. This was a significant change for Armenian readers at the time.

In the summer of 1991, the “Azg” newspaper’s editorial section centered around the dispute between Prime Minister Vazgen Manukyan and Chairman of the Central Committee Levon Ter-Petrosyan. On July 18 of the same year, Vazgen Manukyan announced the establishment of a new political party named the National Democratic Union in a televised speech. The “Azg” newspaper editorial deemed his decision dangerous, stating that it could divide the forces and lead to Moscow’s intervention. “The Kremlin is likely to be the main beneficiary of the current situation. Its local supporters, following the recent pressures in Artsakh, will likely try to destabilize our already highly corrupt government further to eventually coerce us into signing a contract and other agreements against our will.”

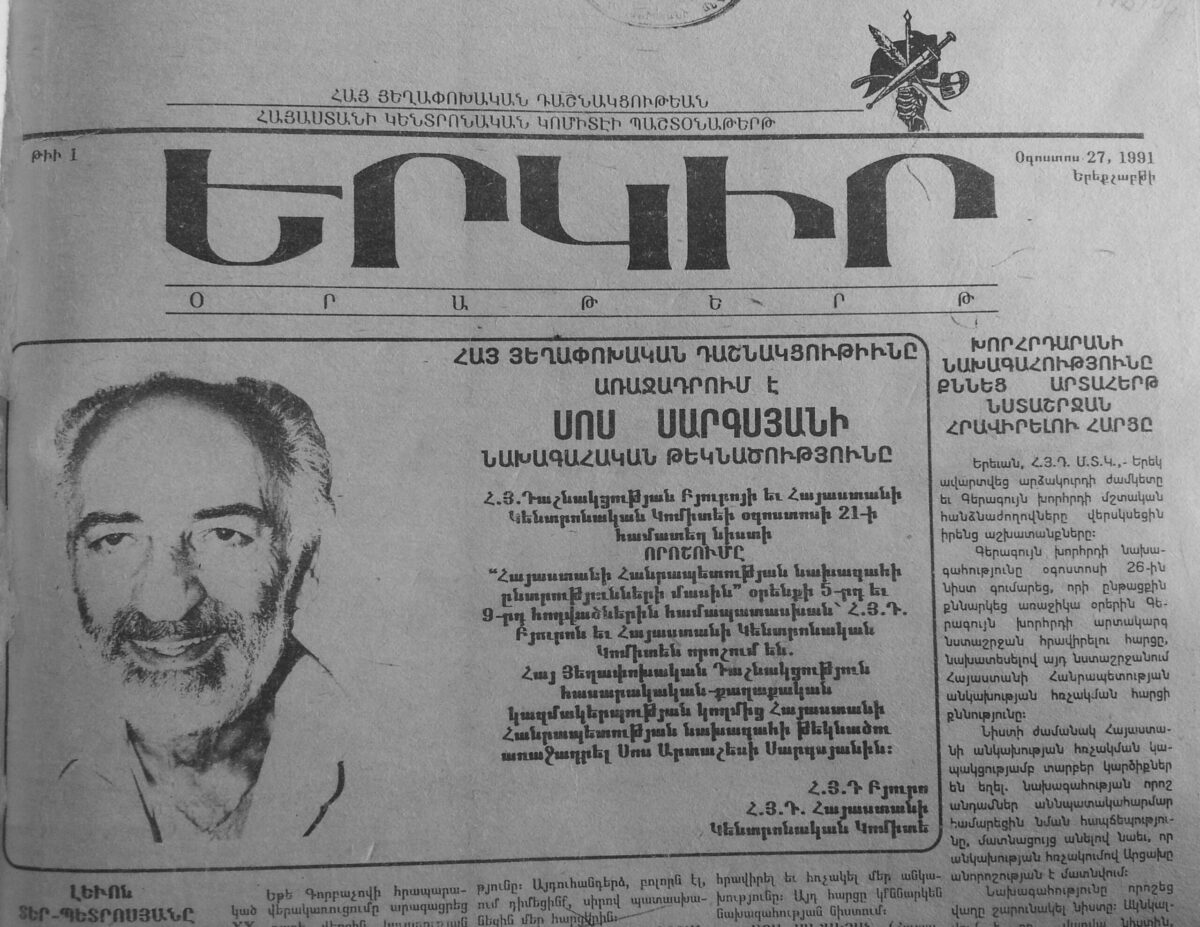

On August 27, 1991, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Party published the official newspaper “Yerkir” in Yerevan. At that time, two important political events were happening in Armenia – an independence referendum was scheduled for September 21, and the presidential elections were set for October 16. These events created a lot of political excitement among the people of Armenia. The first issue of “Yerkir” featured a picture of Sos Sargsyan, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation’s (ARF) presidential candidate, and the ARF bureau’s decision to nominate him. The editorial of the same issue was titled “Yes to Independence” and outlined the newspaper’s main goals and mission. ” “Yerkir” aims to serve the Armenian people and will be a new expression of the ARF’s national service. Honoring those who have shed blood and sweat for the independence of their motherland, The ARF has returned to its homeland and is determined to work hard for Armenia’s independence.”

The editorials of the official party papers operating in Armenia had one remarkable feature: they could present not only the editor’s or editorial board’s point of view but also the party’s perspective. In this sense, the editorials became the official position of the given party. Already in the 3rd issue, “Yerkir” addressed several accusations against the national ideology and the ARF. “The organization with these abilities has become an object of envy in Armenia’s political reality, attracting attention, especially from those at the beginning of their journey. To mask their organizational weaknesses, these groups in turmoil resort to making extreme statements, such as claiming to be the ” most national” or rejecting any national ideology,” was written in the paper.

“Azatamart,” like all the other ARF papers, always took an uncompromising stance against the government. It also strongly emphasized nationalist ideas, demands, and the need to solve the Nagorno-Karabakh issue. One of the key demands that the ARF made was for the government to focus on creating a national army, which the party believed was the main guarantee for the country’s security.

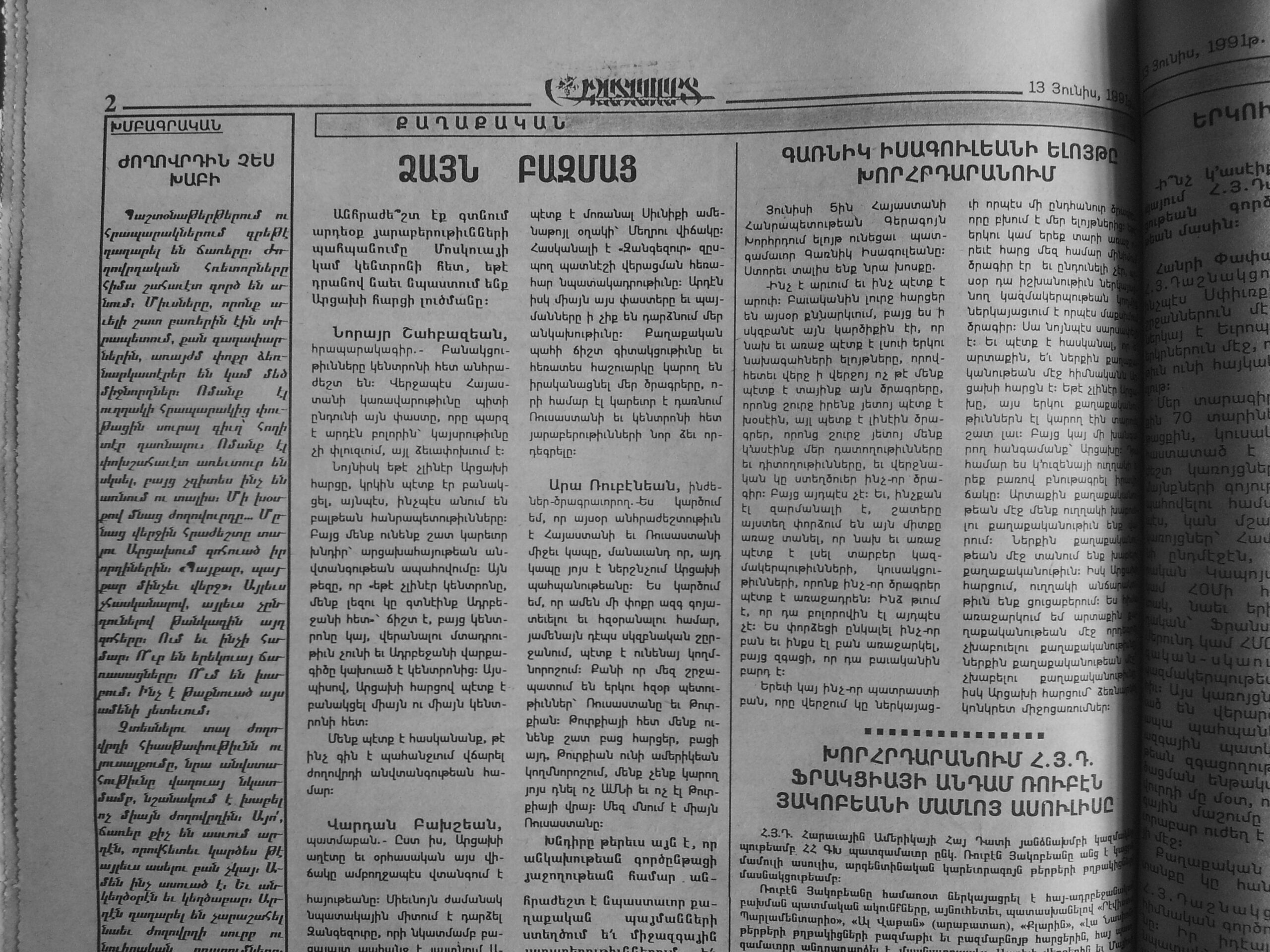

The authorities were criticized because of people’s disappointment and a shift in the stance of the movement’s leaders. On June 13, 1991, the open editorial of “Azatamart” noted that the number of speeches in the squares had decreased because the former “orators” were now engaged in “lucrative business activities.” According to the newspaper, some had rushed to the village to privatize the land, while others were engaged in entrepreneurship. However, despite these activities, the people remained in the village to say the final goodbye to their sons who had died in Artsakh. The article continues by questioning the purpose of the sacrifices and wondering who is deceiving the people and what is hidden behind the curtains. The article also questioned the whereabouts of those vocal about the cause.

The Russian-language newspaper “Golos Armenii” was known for its diverse and free content. Although it was the successor of the former “Communist” newspaper, “Golos” had a national-state stance and did not advocate communist ideas. Unlike other newspapers, “Golos” had no dedicated “Editorial” section. Still, the opinions of various authors published on the first and second pages of the newspaper fully corresponded to the open editorial genre in terms of content. It is also worth noting that the themes of the editorials were more varied, and the “Golos Armenii” featured a more affluent and artistic language compared to other newspapers. While other newspapers mainly covered a few internal political stories, “Golos Armenii” also covered general, international, and other topics.

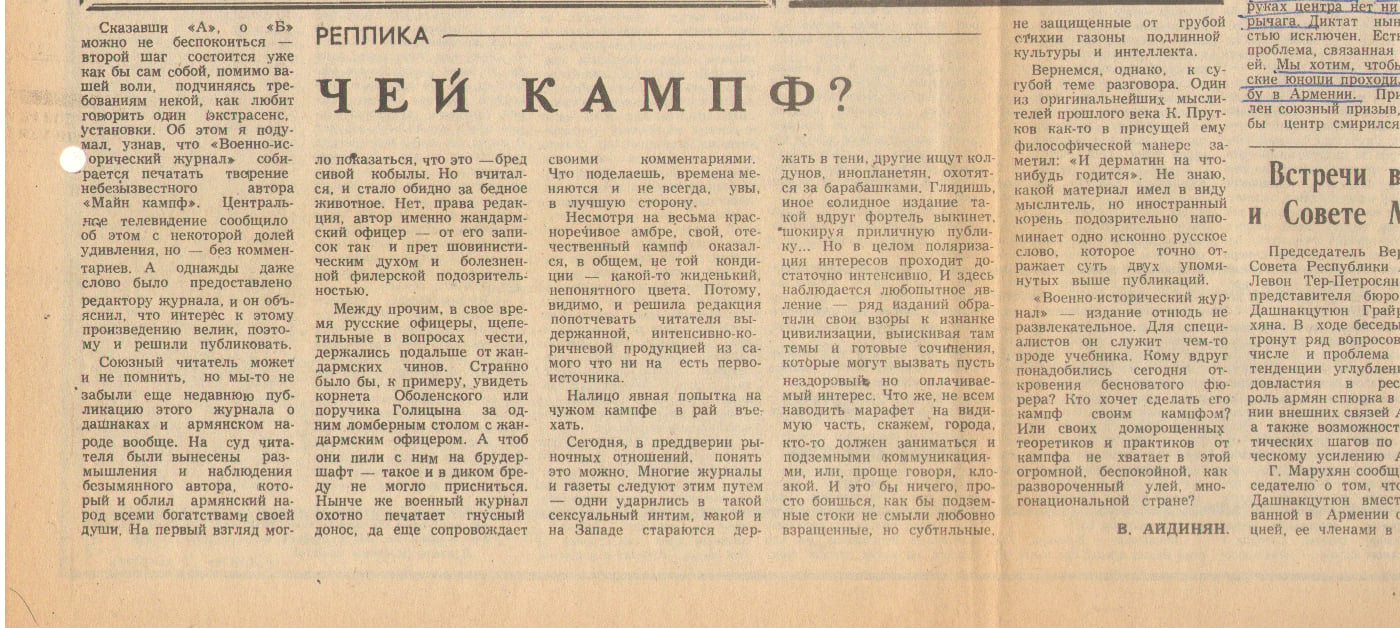

A vivid example is the article “Who’s Kampf” by Golos Armenii’s special correspondent Valery Aydinyan in December 1990. In the article, Aydinyan expresses surprise and disappointment at the decision of a famous military-historical magazine in the Soviet Union to translate Hitler’s infamous work. The author considers the intention to be irrelevant. It’s worth noting that in the early 1990s, along with positive changes, the yellow press emerged, which published sensational news, rumors, gossip, and even utterly fictitious material. In the column, Valery Aydinyan addressed the issue of cheap news and content, which was almost absent in Soviet newspapers. “In today’s market-driven world, many newspapers and magazines resort to sensationalism. Some have gone so far as to delve into topics that are considered taboo even in the West, while others are searching for stories about witches and aliens. Even respectable publications are playing a clever game, deliberately confusing their readers. A noteworthy trend is that some publications focus on the fringes of society, uncovering stories and articles that may pique the interest of some readers – even if it is an unhealthy interest – in exchange for payment.” wrote Valery Aydinyan.

Valery Aydinyan, a special correspondent for the “Golos Armenii” newspaper, regularly contributed a column titled “Valery Aydinyan’s screen” to the front page. In one of his columns titled “All we missed was a dictator,” Aydinyan commented on the important public and political events of the time. The column, published in January 1993, focused on the issue of establishing a dictatorship in Armenia, a frequently discussed topic at the time. It’s worth noting that all authorities in Armenia were accused of having intentions to establish a dictatorship, without exception.Valery Aydinyan argued that the will and desire of the people are necessary to establish a dictatorship. “A statement alone is not enough to make someone a dictator. The people create the dictator by unquestioningly trusting and obeying him. In our current political landscape, no leader commands such blind trust and complete obedience from the people. Even the once popular idols of thousands have lost their popularity,” wrote the author.

The newspaper “Hayk” from the early 1990s in Armenia is worthy of attention. Despite being the official newspaper of the ANM, it often criticized the government. The newspaper did not have a separate editorial title, but it included various author’s columns published on different pages.

In the September 25, 1991 issue, Valery Mirzoyan commented on the “significance” of sit-ins by university applicants and their families and how it had become more important than the exam or knowledge for admission.”We owe the greatest invention of the 20th century to sit-ins, the formation of the future studenthood. In case the reader was unaware, the medical institute accepted 200 students for the 1992-1993 academic year due to the wise decision of the Council of Ministers. If you have any other desires, why not organize a sit-in? It could be an effective way to achieve your goals. For instance, if you aspire to be elected president, a sit-in coupled with a two-day hunger strike could be the answer,” wrote Mirzoyan.

The open editorial of the 100th issue of “Hayk” newspaper, published on December 18, 1991, was a summary of the political events and struggles of the past two years. The article highlighted Armenia’s achievements, struggles as an independent state, and prominent landmarks. It emphasized the need for unity among Armenians and for them to take responsibility for their losses and successes. The article urged people to abandon the habit of blaming each other and to use their resources to win in the nation-building game. Lastly, it called for using those resources in the game against foreign players.

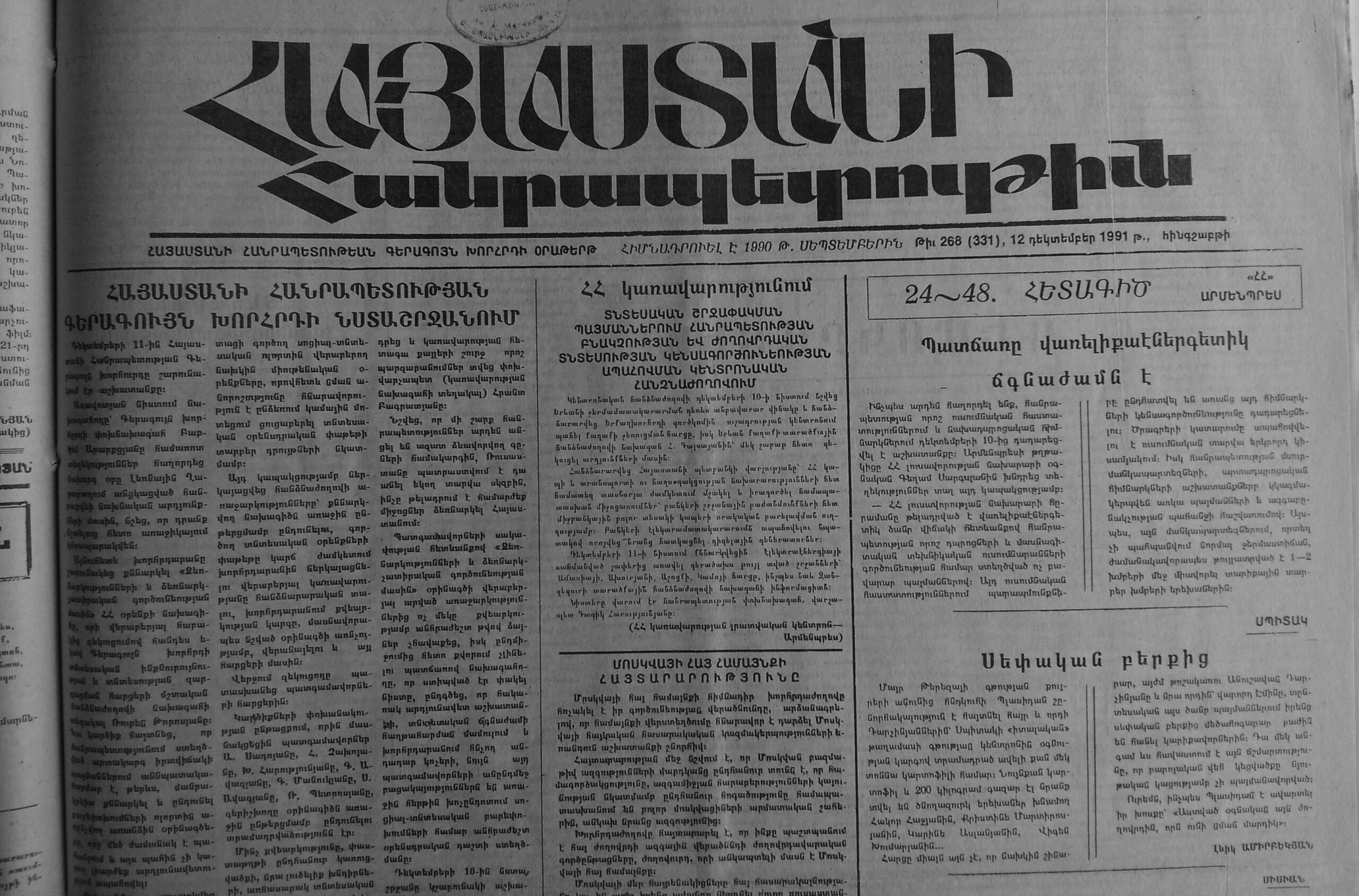

The newspaper “Hayastani Hanrapetutyin” featured many headlines closer to the open editorial genre. In 1991, the main topics of discussion were the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States. There are several significant columns that addressed Armenia’s political orientation during this period. The issue of Armenia’s political orientation was a hot topic from 1988 to 1990 and was actively discussed in both the press and in rallies.

On December 24, 1991, Kuprich Sardaryan published an open editorial under “Hayacq” heading titled “On re-orientation, demand and domination.” In this piece, the author addressed Armenian-Russian relations and stated that Russia is withdrawing from the region while some people in Armenia are still trying to hold onto it. Sardaryan emphasized that it is time for Armenia to recognize its independence, mature as a nation, and overcome the behavior of stateless times. The author called for the country to replace its uncontrollable and selfish psychology with a self-centered national-state consciousness.

The challenges facing the Armenian press were frequently addressed in the columns of the “Hayastani Hanrapetutyun” newspaper. The economic crisis and transition to market relations presented both opportunities and serious challenges. On December 12, 1991, Armenpress correspondent Gagik Martoyan reported in “Hayastani Hanrapetutyun” that the state had ceased supplying paper, leading to ongoing difficulties for editorial offices in obtaining printing materials. Limited financial resources meant that not all newspapers could procure the necessary printing paper. Furthermore, the new press distribution and subscription system had not yet been established, resulting in decreased newspaper consumption. “In the backyard warehouse of the Haysoyuzpechat republican union, “Armenia” and “Golos Armeni”, “Hayastani Hanrapetutyun” and “Munetik”, “Hayk” and “Ankakhutyun”, “Yerkir” and “Azg” often rest side by side… All are there, both the proud veterans of the Soviet press and the children of the “golden age” of the Armenian press. There rests the fourth power of the Republic of Armenia,” wrote the author.

* * *

presence of open editorials and commentaries. These pieces of journalism were not only fascinating but also encouraged free speech, diverse opinions, and public discourse. During the 2000s, political debates and social and public issues were the primary subjects tackled in the editorials and columns of newspapers.

Today, not all Armenian news outlets feature a dedicated section for open editorials and commentaries, which was once a popular genre. However, it may be premature to assume that the genre is in decline. Editorials will likely continue to hold their position in diverse news content and regain their former significance in due time.

Mikayel Yalanuzyan

Part 1

The article was written and published within the framework of the “Competing Narratives” project implemented by the Media Initiatives Center and n-ost.

[1] Ashot Sargsyan, History of the Karabakh movement (1988-1989), Yerevan 2018, page 261. See also: 12.10.1988, page 2.

[2] Hayrenik, Yerevan, September 1988, pp. 3-6.

[3] Hayrenik, No. 7, January-February 1989, page 7.

The views expressed in the column are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the views of Media.am.

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.