With the first creative-symbolic competition was held on “June 14,” the Eurasia Partnership Foundation aimed to popularize the knowledge about the Soviet period of Armenia’s history, to have a conversation, to create a platform where the stories of the repressed will be collected for publicity.

June 14 has been marked as Remembrance Day for the Repressed since 2006, and in 2008 a memorial to the repressed was opened in Yerevan, at the top of Cascade Highway, of which few people know of.

The works submitted to the wide-ranging and informative “June 14” contest were very different, variegated, and multi-genre: essays, fiction, scientific and documentary material, books, archival documents, photo history, scientific articles, documentaries, feature-documentary films.

The online summary after the contest was more like a starting point for a conversation, a topic, a conversation, which was both interesting and disturbing.

According to 2019 data, there are a thousand people in Armenia who are 80-90 years old and have the status of having been repressed or are the first-generation descendent of one who has been oppressed. Again, they are ignored, their stories are unwritten.

The list of those repressed in 1930-1938 was first published in the Republic of Armenia newspaper in 1993 under the title “Let’s Remember Name by Name.” 14,904 people were arrested during those years, 4,531 of them were sentenced to death. In 1939, there were 11,064 Armenians in the Gulag.

And during the whole wave of repressions (1920-1953) the number of Armenians who were repressed is 42 thousand.

If you live abroad, you’d write “Gulag archipelago,” or if you are a repressed Armenian writer Mahari, you’d write “Flowering barbed wire” in the 60s, which would be published only in 1988.

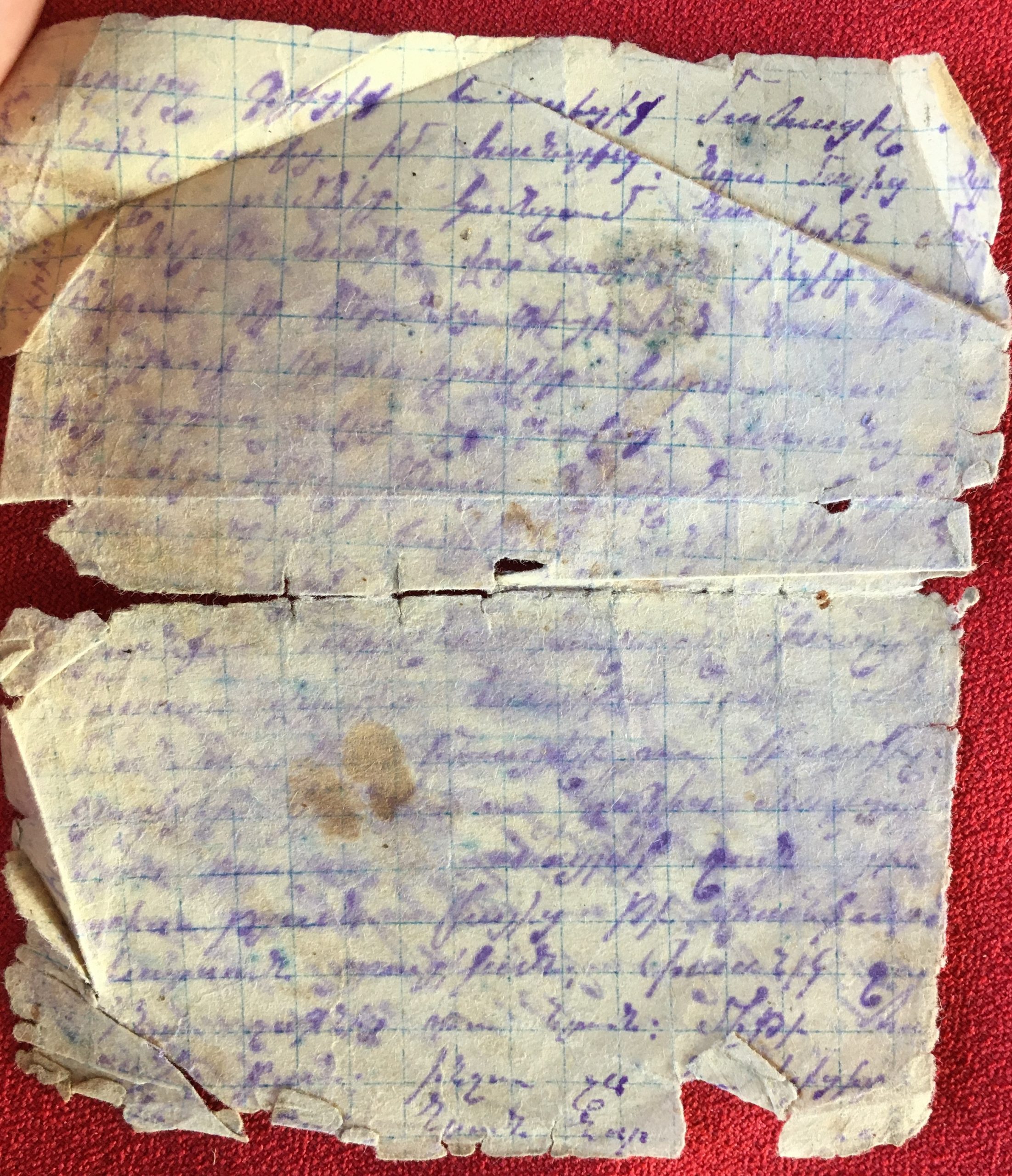

And who would write about them – 42 thousand people who, according to Hrant Matosyan, go down in history as statistics, the memory of them is limited to the suffering, calligraphic, fragmented letters sent home.

To write about the oppressed today would be to interpret the voice of silence.

Born into a family of immigrants – to be silent – to know nothing about the Genocide, to be the son and grandson of the oppressed and not to talk about it – in the twentieth century of our history this Mancurism became possible in Soviet reality.

To tell, to tell again

The competition coordinator Nane Paskevichyan informed at the beginning of the online discussion that they had received 28 applications – many applications for books and films, and it was difficult to evaluate because all the materials were equal and at the same time very different. They were equal because the main motivation of the materials is the preservation of memory, the authors are modern historians, preserving and disseminating that memory.

The materials were evaluated by a professional commission: Eviya Hovhannisyan, Tigran Amiryan, Anahit Keshishyan, Susanna Shahnazaryan, Sara Khojoyan, and as a result of a long discussion, the main prize was awarded to Armen Ohanyan for the essay “In Memory of Remembrance,” special prizes were awarded to Rubina Pirumyan “Stalin Gulag from Tabriz: An Interrupted History,” Hasmik Alazan’s “Through Paths Of Suffering,” Gohar Stepanyan’s “I Complain With Deep Indignation.”

According to the executive director of “Eurasia,” and novelist Gevorg Ter-Gabrielyan, “there is no discourse, there is no chain, activities on this topic in Armenia have become very difficult, priority is not given to it and it is not welcomed, and that part of our history disappears in the Soviet infrastructure.”

According to jury member, literary critic Anahit Keshishyan, there was a huge amount of good material in the competition. The topic is complicated and repulsive. “For example, reading Solzhenitsyn was torture, and two major traumas could not be accommodated, so they did not receive a fair description and assessment.”

Award-winning historian Rubina Pirumyan recalled her experience in writing the study “All the Oppressed in Siberia” in English to draw attention to the most neglected issue, based on the story of her repressed father, in 2019 her book “Stalin’s Gulag from Tabriz, 11 years in Norilsk” was published in Armenian.

Hasmik Alazan was grateful that the relatives of the victims of the cruel times were given such an opportunity to tell their stories and tell them again.

Gohar Stepanyan, who received the award, studied the petitions of the relatives of the victims, was surprised by the fact that they were mainly letters of protest, in which the position of the citizen was a priority, and demanded justice.

Ethnographer Hranush Kharatyan, who is also focusing on this topic, said that there is a lot of information in the competition materials, which in turn brings up many aspects and parallel topics.

It turned out that Vahe Gharibyan, a teacher at the Mkhitar Sebastatsi Educational Complex, had participated in the school’s “Repressed” project years ago, during which 12 out of 100 people aged 20-40 knew what the repressed were. According to Vahe Gharibyan, the difference between the genre and means of the competition materials, the artistic and scientific works were not comparable.

Ethnographer Gayane Shagoyan noted that we were late for the students in terms of remembering. He emphasized the importance of remembering, not only as a measure of respect but also as a tool for identity formation.

During the discussion, winner Armen Ohanyan said that “it was decided to close the issue with a monument, so it is not accidental that the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs deals with it, the issue of benefits-compensation is solved in case they need intellectual care.”

A cursory look at the 1994 Law on the Repressed and the draft law on the Social Protection of the Rights of Persons with the Status of the Repressed, adopted a year ago in September 2019, reveals that Armen Ohanyan is optimistic.

Benefit and compensation are not unimportant in this case either, as people with that status are 80-90 years old, it just does not exist, no matter how surprising.

We have literally nothing for the social protection of the repressed, the previously established benefits (12,000 AMD monthly allowance, preferential loans) do not work, and the new project, which aims to “partially compensate the moral debt of the state,” is not yet a law.

The competition was an opportunity to inventory how casually and indifferently we are in re-evaluating our past.

Gayane Mkrtchyan

The views expressed in the column are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the views of Media.am.

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.