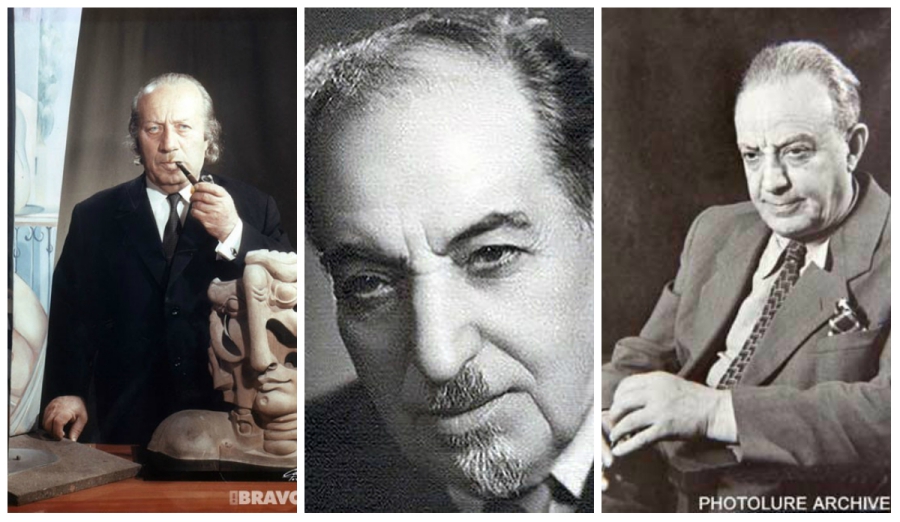

In the 1940s, the only, and moreover, extremely difficult way to get audio from Armenia to any corner of the world was radio. The Communist Party also used that route and through the voices of artists and scientists living in Soviet Armenia appealed to Armenian communities in the diaspora. In Avetik Isahakyan’s, Yervand Kochar’s, and Vahram Papazyan’s personal archives, there are texts that are titled “Radio message to diaspora Armenians.”

The Public Radio Armenian Wiki notes that the first message directed to the Diaspora was broadcast in 1947. Yet calls to diasporan Armenians were sent from Armenia through radio messages during WWII (1940–1945), sometimes employee of Public Radio’s art and literature section and radio “old-timer” Clara Terzyan informed us in conversation.

The Soviet policy toward the Diaspora had clear goals.

First, diasporan Armenians’ financial support was expected during the war. It’s well known that it was through diasporan Armenians’ efforts that the Sassuntsi-Davit Tank Regiment with its 21 tanks was established in 1944.

The Paris-based newspaper Zhoghovurd in its August 15, 1945 issue printed Avetik Isahakyan’s radio message to diasporan Armenians:

“We know that your patriotic views are directed toward Armenia. The Armenian people devotedly participated in the sacred Patriotic War, against facism and reaction. Standing beside its older brother, the heroic Russian people, it fought like the brave, defending the great homeland and its culture. The great Soviet Union won.”

The other purpose of the calls from Armenia to the Diaspora was to create among Armenians living abroad the sentiment to return to the homeland. The radio broadcasts were one of the effective tools of presenting Soviet Armenia attractively. The immigration from the Diaspora known as the “Great Repatriation” happened in 1946–1948.

Organizing the radio broadcast was technically extremely complicated and laborious. “The equipment would’ve been 100 kg,” says Clara Terzyan. “We would move the recorder and huge speakers with a big car. We would take them up to the apartments of writers and artists as, for example, in the case of Avetik Isahakyan. In 1955, it was already difficult for him to get out of the house.”

It was hard carrying the heavy equipment up to the apartments, and over time they found a solution: the equipment would remain in the yard, while the microphone would be taken upstairs, connected by a long rubber pipe.

But this wasn’t the only difficulty: until the late 50s, the radius of Armenia’s radio broadcast was small, and the stations, weak. Broadcasting to the Middle East, Europe, and the West wasn’t possible.

“They would come from Moscow to Yerevan. One of the suites at the Intourist Hotel [present-day Grand Hotel Yerevan] was turned into a recording studio. The writers and scientists would go there and be recorded. And then the recording would be flown to Moscow, and they broadcast from there,” says Terzyan.

From 1957, programs from Yerevan began to be directed also to diasporan Armenians living in Europe. On this occasion, the first remarks to diasporan Armenians were made by actor Vahram Papazyan.

“Far and always close Armenian listeners, adults and children, beginning today are radio broadcasts from Yerevan for Armenian hearts scattered in distant lands, palpitating under a different sky. I am happy that I have been given the opportunity to make welcoming remarks to you from our homeland — our prosperous, moving ahead at a fast pace, reborn Armenia…” (Clara Terzyan, from the book Buyl Medzats, 2001, pp. 107–108).

In the radio broadcasts, there were also calls not to forget the mother tongue. Here is an excerpt from sculptor, painter Yervand Kochar’s 1968 radio broadcast:

“Keep and preserve the Armenian language, keep bright the [pagan] temple keeping Armenian culture warm, that is in all our hearts and that we bring from very distant centuries, time immemorial” (Yervand Kochar, Yes ev Duk [Me and You], 2007, p. 194).

It’s interesting that heard through the radio broadcasts were indirect hints about not losing the ambitions toward the historical homeland. “The injustice of the first Imperialist war toward the Armenian people must be eliminated. Saved from the barbarians with the help of the noble Russian people, the wayfaring, persecuted Armenians must get their inherent right: the liberated homeland. And our centuries-long aspiration will be fulfilled — to be able to work on the cherished lands of our fathers and enjoy the sweetness of the homeland.

“Armenians abroad, wholeheartedly, with one heart and one soul, should contribute to this great and noble cause” (Avetik Isahakyan, Zhoghovurd newspaper, August 15, 1945, Paris).

This is from Yervand Kochar’s radio message. “We never and not for one minute forget that we have brothers, scattered all over the world … We not for one minute forget that if an Armenian’s head is here, the strings of his heart are spread all over the world and vibrate, they live everywhere with the same vibration where there is an Armenian, with the same sense of joy and frustration” (Yervand Kochar, Yes ev Duk [Me and You]).

Since 2001, Armenian radio has stopped broadcasting radio messages to the Diaspora.

Lilit Avagyan

The views expressed in the column are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the views of Media.am.

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.