In Diana Markosian’s photographs, there is memory, and there are people who carry the past. The photographs also are about the present and speak in the language of their subjects — from Beslan to Burma.

Diana’s photographs have been published in The New York Times, TIME, and Foreign Policy and received professional awards. Diana Markosian was born in Moscow, then moved to the US and studied at Columbia University.

Looking at your list of publications and online exhibits, I see an important professional event every year. What was remarkable about last year?

It was an important year for me. I noticed myself mature both personally and professionally. As a photographer, I am slowly re-defining my voice and starting to understand the type of work I am interested in pursuing. Much of it is driven by the unknown. That’s what 2014 was for me. Most of what happened wasn’t planned and took me by surprise.

School No. 1, Beslan

On Sept. 1, 2004, terrorists in North Ossetia took 1,200 people hostage in Beslan’s School No. 1. Of these, 334 were killed; more than half were children.

“Mister Ali, can I please have some water?”

“What kind of Mister am I to you?” answered the masked man.

“I am a terrorist. I am here to kill you.”

Zarina Albegoeva, 11

I get the impression that your photos are not just art but have some connection to anthropology, human rights, and journalism. Do you think about these fields when you cover an event or go to a country?

I realized I am not interested in just creating beautiful images. By using archival images, drawings, and text, I am allowing my subjects to tell their own stories. This has become a larger part of my work and something I want to continue to develop.

Classroom 15, once used to teach Russian, became an execution chamber. The terrorists shot and killed more than 20 men the first day.

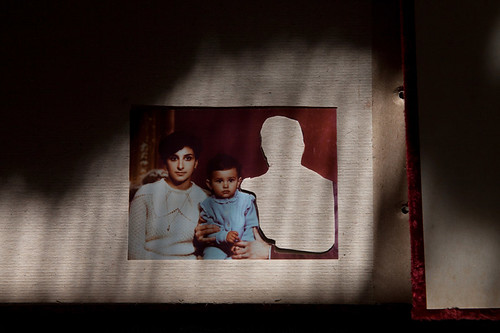

For most of my life, my father was nothing more than a cut out in our family album. I have few childhood memories of him. In one, we are dancing together in our tiny apartment in Moscow. In another, he is leaving. One day, it was our turn to leave. The year was 1996. It took me fifteen years to be standing where I am. Outside the courtyard of his home. [Full text can be found here.]

In The New York Times Sunday Review I read your article “My Father, the Stranger”. I saw your grandfather’s suitcase with the unanswered letters. You write how after a separation of 15 years, you came to Armenia to meet your father. As a photographer, did you have unanswered letters in mind? Did you write to Armenia?

This piece has allowed me to better understand my father and my origins. That said, I can’t say being Armenian is my only identity. I feel like I am a composite of many things. My ethnicity is Armenian, but I was born in Russia and raised in America.

I don’t identify with one specific country or people but many. I think this has helped me immensely in my work and enabled me to relate to people everywhere from Burma to Chechnya.

My parents met in university in Armenia. They look so happy, so in love.

My parents met in university in Armenia. They look so happy, so in love.

In 2011, you were denied an entry visa to Azerbaijan. What were you going to do there, if they permitted you to enter?

I was on assignment for Bloomberg magazine, working on a piece about organ trafficking.

Beslan, Afghanistan, Chechnya, Chernobyl: these are places you’ve “entered” and covered. There is an overall opinion in Armenia that the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is not properly covered by the international media. What do you think?

I am not sure. I haven’t researched enough about Karabakh to know what sort of projects have been published.

He opened a suitcase filled with newspaper clippings, undelivered letters and a shirt for my brother’s wedding.

He opened a suitcase filled with newspaper clippings, undelivered letters and a shirt for my brother’s wedding.

This year is the centenary of the Armenian Genocide. I saw a section called “1915” on your website, but I was unable to open the page. What’s in the works?

I am working on a new project about this topic, which includes interviews with survivors of the genocide who I’ve met in Armenia. I also visited the origins of where these survivors escaped in Turkey to photograph the cities, the streets they left behind. The project will be a compilation of images both from Turkey and Armenia as a way of bridging the past and present.

Thank you.

Armen Sargsyan

Photos courtesy of Diana Markosian.