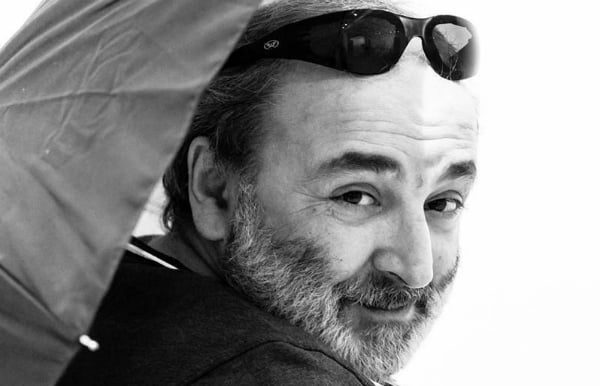

Photographer German Avagyan prior to photographing tries to plunge into the situation and destiny of man as much as the situation and his emotions permit. He talks with his subject for a long time, befriending him, asking questions, and most importantly, listens. What he hears and experiences becomes a framed instant, always with a story behind it.

A photographer’s professionalism, after all, is to allude to a story and not just spread glorious, stunning, or scandalous images.

Avagyan has not only worked as a photojournalist (including for CNN), but also created his own documentary photo projects. He is convinced that every photo should change a viewer, or at least motivate him to think and emotionally enrich him.

One of the problems of the Armenian media industry, according to Avagyan, is the devaluation of the journalist’s and especially photojournalist’s profession. One of the reasons he wants to establish a photography school in Yerevan is to change this. “Let me tell you a secret: no photographer can teach anything; teaching in general is impossible — we can only work together. I want us together to choose, build, and feel the pleasure of contact with [celluloid] film,” he says.

The advent of the internet first and foremost had an effect on the visual arena. Our life was filled with an enormous amount of images, becoming muddled. How did this onset of images affect the media industry?

Journalistic and documentary photos are different. I find that a photograph is not a postcard but a story, and I have been working for years according to this principle. The internet had an effect on not only photos, but also text. What, don’t news articles [also] confuse? Words are just as much and often of low quality as images.

What makes me more angry is that in Armenia, everything is done to discredit the journalist’s (and especially photojournalist’s) profession.

Created is the image of an aggressive, semi-literate journalist, who invades people’s lives and photographs whatever he wants and acts however he wants. Either the authorities are extremely smart, that they are able to devalue a journalist’s profession to that degree, or the public is unprepared to resist.

In Azerbaijan, for example, journalists are thrown in jail, while here [in Armenia] they are discredited — putting them on the same platform as unprofessional, aggressive, arrogant people. There is freedom of speech, but speech has no value, since they can tell you, well, aren’t you that? And it turns out that I too am the photojournalist, the so-called semi-literate, but the famous one al

Serious effort is needed to raise the reputation of journalists and not imitate the journalistic community that recently earned a monument.

What to do when the news is shocking, about a death — is it necessary to show the deceased, blood, the accident, disaster? Journalism ethics and the debt to illustrate the reality often contradict each other.

The issue is not journalistic but simple human ethics. I’ve always said that the faces of the deceased shouldn’t be photographed or shown. After all, the photojournalist’s professionalism prepares him to take such photos where the disaster is evident but the deceased’s face isn’t seen.

|

“A photograph has more of an impact than video: the advantage of photo over video is the quality of being remembered” |

I remember, after the 1988 earthquake, seeing a photo among many photos that depicted several coffins in a residential yard. All the deceased people’s faces were covered, but one was open, uncovered.

I asked the photographer: how did they forget to cover [it]? He said, I opened it; I wanted to take a more compelling photo. I’m convinced that he had no right to do that; a face is a person’s possession. Even after death no one has the right to exploit that possession.

It’s a violation of human rights; even if a photo that has a huge effect is produced.

Even in the cheapest Hollywood films we see the first thing they do is cover the deceased person’s face. The police officer approaches, takes off his jacket and quickly covers the corpse’s face. That’s the order.

Death and disaster are more compelling in photographs than when they’re described in words. And the media wants to produce compelling stories.

What’s the point of photographing a man lying in a coffin? If they write that he died, won’t that be enough, won’t they believe it?

There are photographers who easily photograph [the deceased] — I can’t. When during [a training run at] the 2010 Olympic Games, an athlete died, I went to Bakuriani [Georgia] for the funeral and took photos. But what interested me more was not the deceased, but the ritual, the preparation for the ceremony. In some shots the coffin is also seen, but I’ve never exhibited those photos. From the photo it’s clear that it’s a funeral — why is it necessary to show the face of the deceased?

You understand, a person is a being that experiences a limited number of emotions. And if the media wants to produce a compelling piece, it has to calculate that limit; otherwise, it will have the opposite effect. Instead of being shocked, the audience will become more indifferent.

There is a threshold of emotions, which when passed, people cease to understand and feel pain and danger. Everything becomes all the same to them. If you show a video a hundred times and share it, people will stop understanding for a very simple reason: their understanding will deteriorate.

That’s what happened on Sept. 11, 2001, when the twin towers in New York were blown up. I was living in the US at the time, and I remember how the images of the explosion affected people. First, there was horror and sympathy, then the emotions deteriorated and the response diminished.

|

“What makes me more angry is that in Armenia, everything is done to discredit the journalist’s (and especially photojournalist’s) profession. Created is the image of an aggressive, semi-literate journalist, who invades people’s lives and photographs whatever he wants” |

If a photojournalist is disciplined, he won’t photograph the mentally ill, say, naked or in a degrading situation. If person with a mental illness moves in a way whereby her breast becomes visible, I would cover not only the lens, but also my eyes.

I know an auteur who worked on a special project at a hospice, photographing people before and after death. They were very interesting portraits.

But the auteur probably received permission from these people while they were still alive. Furthermore, the photographs were the result of several years’ work and making contact. While here [in Armenia] photographers come, take rapid-fire shots with their devices and immediately disseminate the images.

All your photo projects try to establish links between different years and subjects. Can it be said that a photograph changes the approach toward an issue?

That’s what I always want. For many years I photographed children who became disabled because of explosive ammunition and land mines left over after the Artsakh [Karabakh] War (many of them are now my friends). Yes, a lot changed after that project.

Any documentary project that appears in the media (in a broad sense also everywhere, since everything is media) should have an impact on life; otherwise, why is it being done?

Once, in 1997, I made a serious mistake. I was working at Aravot newspaper, when we received word that someone committed suicide by jumping off the Kievyan Bridge. I quickly arrived on the scene, even before the police and doctors, took photos and left. The photos were printed, but even now, years later, I regret what I did.

I always think, if I had arrived a few minutes earlier, spoke with the person, would I have prevented the suicide? Probably not, but one has to try, since life is one of the most beautiful gifts given to us, and people can be reminded of this through photographs. I propose placing posters near Kievyan Bridge that will remind people of the value of life.

A photograph has more of an impact than video: the advantage of photo over video is the quality of being remembered. It’s not worth it for images to serve useless things.

Interview conducted by Nune Hakhverdyan.

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.