Numerous initiatives mobilizing the society appeared during the Second Artsakh War. There was even a special website, Ognum.am, where you could learn how to help the army. One of the proposed options was to take part in the digital war by joining the relevant groups on social networks.

Most of these groups mobilized people to spread pro-Armenian content and to criticize or “report” non-pro-Armenian content.

The groups quickly gathered tens of thousands of members. Both participants and administrators consider these groups an important tool in countering digital warfare. However, journalists and experts criticize this activity, considering it meaningless, and in some cases, harmful.

Digital activism of tens of thousands of users

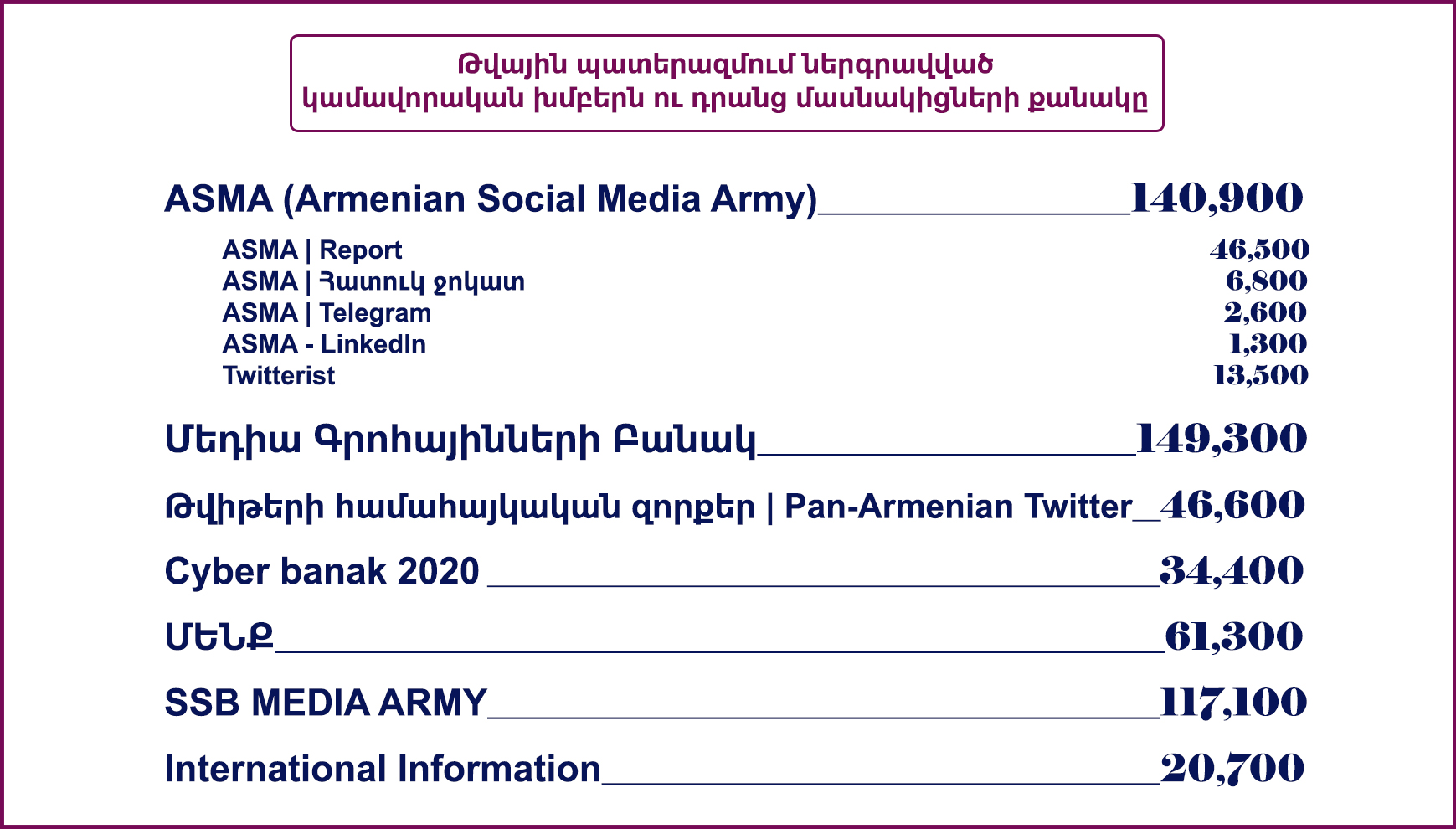

There were more than a dozen groups and pages mobilizing users. Many of them used military terminology in their names: “Armenian Social Media Army” (ASMA), “Media Offensive Army,” “Cyber banak 2020,” etc. In these names, the participants were perceived as digital forces to defend the country in the information war.

The number of participants in the groups ranged from 30,000-40,000 up to 150,000.

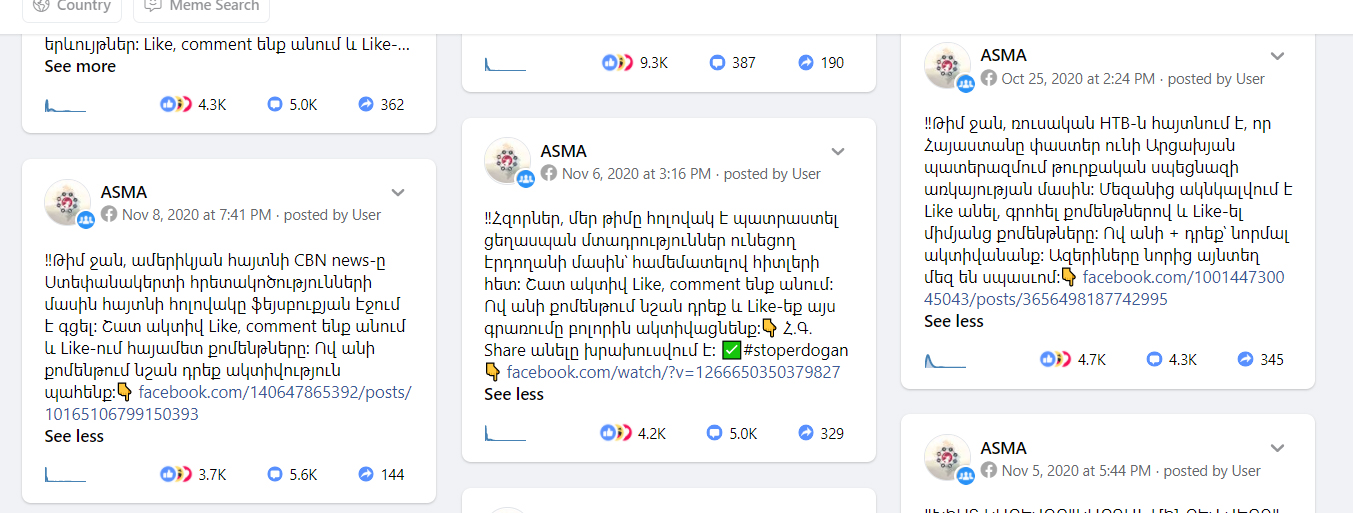

Using the Crowdtangle tool, Media.am downloaded and studied the content of the ASMA Facebook group. ASMA was founded on October 1 and quickly became one of the largest groups in the series: It has more than 140,000 members. During the war, the group’s nearly 400 posts garnered an average of 2,000 likes and comments. The likes and comments of several posts exceeded 10,000.

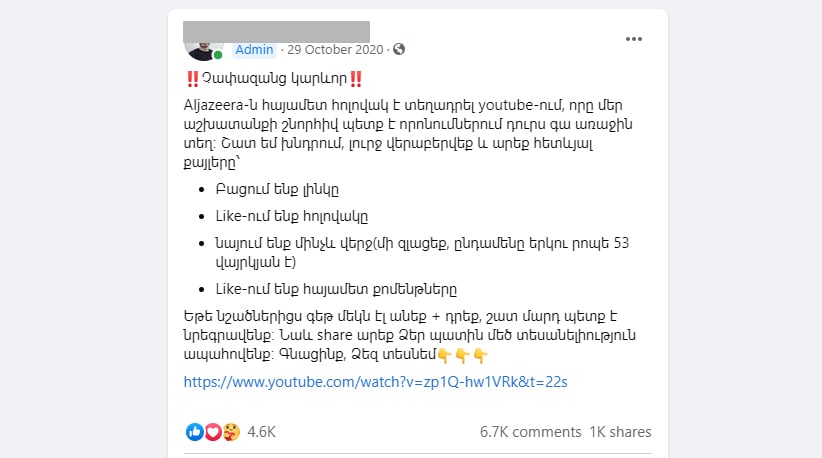

The publications started with attention-grabbing and alerting phrases: “!!Very important!!” “!!Extremely important‼” etc. Most often, the posts urged the audience to take action. The group coordinators addressed the audience as a “team” and directed the action to comment, spread, etc. Posts often contained a description of the steps required, “️Dear team […] We’re going to like, comment and share. Let whoever does it comment with a +, let’s activate everyone. Let’s go.?”

The content of the group was diverse: petitions, positive news from the battlefield or the diplomatic front, most frequently, calls to share or comment on this or that content.

The groups sometimes targeted international journalists, trying to make their coverage more pro-Armenian. For example, the “Media Attackers” group was originally called “Attack Popular News.” Here users were urged to leave certain comments about the war in the international press.

The groups also helped send numerous complaints about fake accounts to social networks, as during the war the Azerbaijani side created fake pages of officials, Armenian media, and even the All-Armenian Fund. ASMA even had a separate group to “report” such fake pages: ASMA | Report.

The activity of these groups was coordinated. That is, the users were not completely independent, but were guided in their actions by the admins. However, these groups are difficult to describe as coordinated inauthentic behavior. They can be described as online activism, as most of the users were real, they were not paid for their activities. Moreover, no widespread use of automated accounts was found.

Maybe this is the reason why both admins who talked to us confirmed that the groups did not have any serious problems (for example, blocking) with Facebook. Nevertheless, Twitter often blocked individual accounts created during the war.

By the way, along with the groups, Armenian celebrities also used their social networking platforms to coordinate people’s online activism. For example, TV host Garik Papoyan often urged people to comment, share or “report” certain content, as well as give advice on how to do it without the risk of getting blocked.

The groups were coordinated by IT specialists

ASMA group coordinator Arsen Harutyunyan learned about the start of the war while in isolation because of Covid-19. Harutyunyan heads the Startup Armenia Foundation. In the first days of the war, the Startup Armenia team held an online meeting and decided that it could be more useful in the information war. “We have a team of designers and videographers and we were quite ready to create content and work on all that.”

As in the case of ASMA so too in other groups, most of the admins are IT professionals with the knowledge and skills to work with information online. Thus, Tigran Mkrtchyan, the founder of another group, the Media Offensive Army, is a digital marketing specialist. “I created the group, understanding the problem […]. It was a voluntary, naturally created group.”

Mkrtchyan notes that working on Twitter was especially important: “Twitter is very important in terms of disseminating information, influencing information. There are many journalists, diplomats and so on there. Twitter is also less popular in Armenia, there were fewer people there and people had to be quickly transferred from Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok and other platforms to Twitter.”

The main platform for groups to gather and coordinate people was Facebook, but the activity was aimed at creating and disseminating content on Twitter. In other words, people in the Facebook group received “assignments” from admins and performed them on Twitter.

The groups tried not to interfere with the government’s information work

The coordinators of the two groups who spoke to us did not agree to describe the activity of the group participants as directed. “You are simply informing, not forcing something to be done. In other words, a person is free to decide what part of it he will or will not do in general,” said Arsen Harutyunyan.

Both Harutyunyan and Mkrtchyan said the government did not intervene or direct their work. “We were watching what the government was doing, what they were publishing, in what direction they were heading. We tried our best not to interfere, or to at least strengthen that strategic direction more, but there was no concrete direction, etc.,” said Tigran Mkrtchyan.

Why did people volunteer to join the “digital forces?”

The participants were ready to perform the “tasks” of the admins. For the tens of thousands of members of these groups, it was a way to satisfy a psychological need to be useful.

Yerevan State Medical University student Marie Simonyan, who was an active member of the group, said, “During the war, I volunteered for a few days, sewing sleeping bags in the village, warm coats, and I felt very strong from the little work I did when I got home. Because of Covid, I could not participate in that work any longer and I was at home. I followed the activities of almost all FB groups, mostly following the instructions. After every pro-Armenian post, I thought, at least this is how I will make my contribution. I tweeted with great enthusiasm, especially in English. I thought, how can the civilized world be silent if, for example, it sees the maternity hospital being bombed? In short, I thought I was making my voice heard in the world.”

Copywriter Maria Ulikhanova also participated in group activities․ “I was active, yes, I even registered on Twitter, I followed, I shared. The reason is that I really believed that it could help, that something would change.”

Group coordinators also emphasized the desire to help people. “The goal of such groups was to unite everyone’s potential. Everyone was fighting their own struggle somewhere, and when you become a participant in that struggle with 140,000 people, its effectiveness is completely different,” said Arsen Harutyunyan.

Did the groups help or hurt?

Not everyone agrees that the work of the groups was effective. BBC journalists Jonah Fisher and Grigor Atanesyan criticized the coordinated activity of Armenian users.

This started on day 1 of this conflict both on Twitter and Fb. These are not just bots. Many are real Armenians, convinced they are doing their patriotic duty by harassing journalists. I know some personally. The damage they do to the Armenian cause is significant. https://t.co/IRh7LuKpDg

— Grigor Atanesian (@atanessi) October 10, 2020

Media expert Arthur Papyan also thinks that the groups were not particularly useful. According to Papyan, the participants’ psychological demand to be useful during the war is understandable, but he considers this activism to be slacktivism, that is, people try to satisfy the desire to help by liking or commenting with little effort.

“Another issue is that in some cases the administrators were busy with quite hard work. They almost always had the best intentions and tried to do something useful. But it did not always work out also because people, yes, were engaged in slacktivism, they did not want to make more effort themselves. Because of that, the coordination became obvious and it for sure caused damage” said Papyan.

In the very first days of the war, researchers at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute published a report on the suspicious activity of Armenian and Azerbaijani accounts on Twitter, highlighting coordinated behavior, copy-paste of the same content, targeting journalists, etc. The topic was also covered by the international media.

According to Arthur Papyan, the creation of these groups was a reaction to the Azerbaijani activity on social networks. “We have seen [Azerbaijani activity] in the past, during the July developments and various escalations, on topics related to Armenia. Let me say that the activities of the Azerbaijani side have not been particularly useful or effective either. It was noticed and in some cases it led to the blocking of Azerbaijani groups by Facebook.”

Karine Ghazaryan