In Soviet Armenia, the Armenian Genocide was a taboo topic.

It was passed on through family stories and survivors’ memories and reflected in literature, but it wasn’t discussed in public forums or in the press.

The USSR renounced territorial claims on Turkey and considered any national issue a threat.

The situation changed in 1965, when on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, there were mass demonstrations in Yerevan. The will to respect the memory of the victims became one of the circumstances of national awakening. Thousands of demonstrators gathered in Lenin (now Republic) Square and marched to the Pantheon, where they placed flowers at Komitas’ tomb, then returned to the square. Posters with the inscriptions “Return Our Lands” and “Recognize the Genocide” appeared.

This spontaneous rally was made possible due to a few prerequisites: the Khrushchev years lowered the pressure to some extent, and furthermore, in 1964, Armenia’s leadership (led by First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia Yakov Zarobyan) wrote a letter to Moscow proposing “to organize events dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the mass killings of Armenians,” including to publish books and articles, produce radio programs and films, and build a memorial complex. A few years later almost all of these initiatives were realized.

An official meeting dedicated to the Armenian Genocide took place at the Opera and Ballet National Theatre on April 24, 1965. The indignant demonstrators moved toward Opera Square, where they engaged in clashes with police.

Stones were thrown that broke the windows of the theatre and harmed some people (including Yerekoyan Yerevan newspaper editor Vruyr Sargsyan). To disperse demonstrators, police used water cannon vehicles, which poured cold water on demonstrators. The meeting happening inside was disrupted.

The gist of the demonstrations was the urge to respect the right to remember and mourn. The public demanded a sacred place that could symbolize the collective memory (the Pantheon didn’t have that role). Bold were calls for the return of lands, which Armenia’s authorities kept semi-restrained and semi-active, by putting some pressure on Moscow.

The public revolt became the impetus that helped get the permission needed to build a genocide memorial complex.

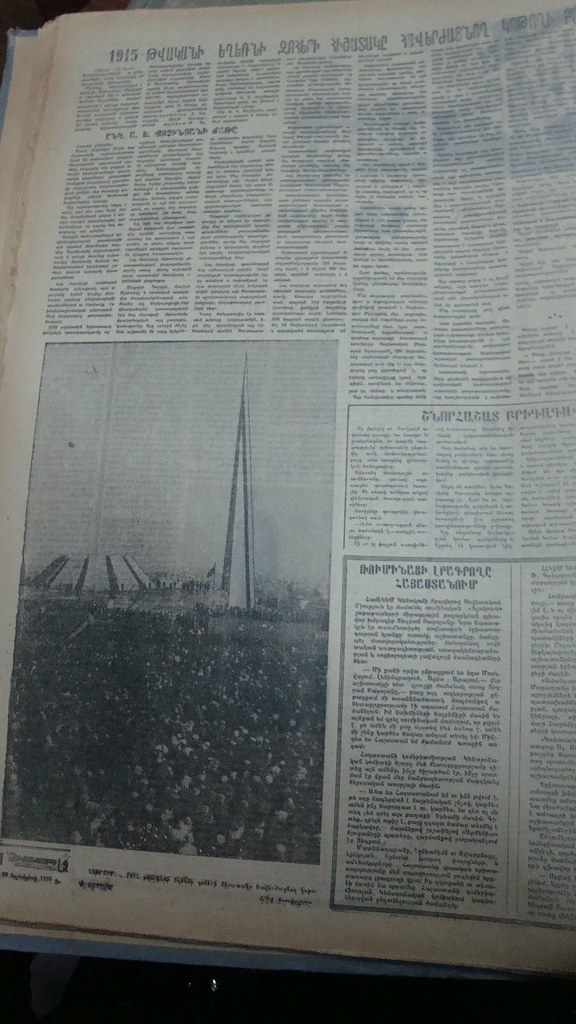

The inauguration of the memorial complex dedicated to the memory of the Armenian Genocide victims took place on November 29, 1967. The memorial complex built on Tsitsernakaberd Hill was a reality, which received significance all over the Soviet Union and was widely reported by the press.

Sovetakan Hayastan (“Soviet Armenia”) newspaper

Sovetakan Hayastan (“Soviet Armenia”) newspaper

Avant-garde newspaper

Avant-garde newspaper

Avant-garde newspaper

Avant-garde newspaper

The Soviet authorities chose as the day of inauguration November 29 — the 47th anniversary of the establishment of Soviet rule in Armenia. The two architectural components of the memorial complex — the Memorial Hall (with the Eternal Flame) and Column of Rebirth — were joined under the rubric “Rebirth”.

Generally, having significant calendar days overlap is a smart move, which allows adding different contexts to an officially declared day — in many cases, even “upgrading” the meaning of the day (years later, the same approach was applied to VIctory Day with May 9 being considered Victory Day not only for World War II, but also for the Karabakh War).

Two historic realities became linked: the images of a tortured, lost, and massacred Armenia in the past, and safe, better, and happy Armenia in the present. Survived and reborn.

Soviet Armenian newspapers in their grandiloquent and pathetic texts wrote about having an “eternal living monument for unburied martyrs” and “prospering in the united family of fraternal peoples”.

Avant-garde newspaper

Avant-garde newspaper

“The heart of each person visiting this monument is filled with hatred toward evil, toward war, toward genocide, and with deep gratitude toward the regime and party that saved our people from horror,” wrote Sovetakan Hayastan (“Soviet Armenia”).

And adding for international emphasis: “This obelisk protests not only the past, but also present imperialist policy, against every manifestation of genocide.”

Mentioned was the “wild judgment against America’s black people, which recalls the Middle Ages” and the “flowing blood of the Vietnamese people”.

The topic of the Armenian Genocide, appearing in the Soviet Armenian press, became a unifier of such multi-layered and diverse narratives.

Nune Hakhverdyan

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.