Photographer Areg Balayan has presented in his MOB. Photo Exhibition what he has lived through and seen from April 2, 2016 until June 1, in the northern border of Artsakh, in the “Yeghnikner (Deer)” military unit. The photos have been published for the first time in the exhibition.

You think of everything

I did not take a camera on April 26, because it was not clear where we were going, it was not clear if I would come back or not, it was not clear if I would take photos, or not. I was thinking about many things…

When on April 14 we arrived to shift for the first time, my camera was with me. That entire time when my camera was not with me, I was dying of not taking photos, I even began making drawings, which also found a space in the exhibit. The drawings I painted with red are already memories of any event that occurred and became important for me.

From April 15 I already began taking photos until the end of June.

There I was in reality a soldier, my primary function was to be a soldier, and I was photographing mostly during the relaxed times. There is no activity in the photos, because during the operations I had an automatic in my hand.

Weighing gains and losses

The Azerbaijani drones take more photos of us, than we do. In this sense it is a little frivolous to say that we can’t take photos. You open Google, and you can see everything until the largeness of a person’s size. However, if there is hostility, if there is military equipment or covert techniques, it is obvious that it should not be photographed.

What is more interesting for me are people, human realities, their experiences, their “standby” state. There was no connection for us, in the first ten days there was no information about us, and we also did not have any news from home.

There were situations that I did not photograph, I wanted to photograph them, but I had to think before taking photos. There are things that if you photograph, it is possible that you will harm a person. In similar cases it is better to not photograph. Globally those photos may do something to help, but will harm many people.

You must remain human in every case, not only as a photographer, in any situation, even if you are building a bridge. I always think, is what I am going to do going to be of help to anyone?

At the border everything was very specific, they were specific people, specific situations. You become responsible for specific people, and if you do one wrong thing, people may be affected, regardless of whether it is fair or not.

Postcard photography

In recent years there are many postcards of the army’s visualization, and it weakens the people’s perception of the seriousness of the army, because people think that everything is normal. One of my goals was to show that not everything is as it appears on the postcard. For example, that there is mud, that fills up in your shoes, and for hours you must stand like that.

I wanted to show how the soldiers sleep (we are 25 people with 6 sleeping spots), how they eat, how they face loneliness, it is you, and the world. It is necessary to show this, so that people are not cut off from reality.

To be honest I do not know, if I had not gone as a soldier, would I have been able to take photos of all of this?

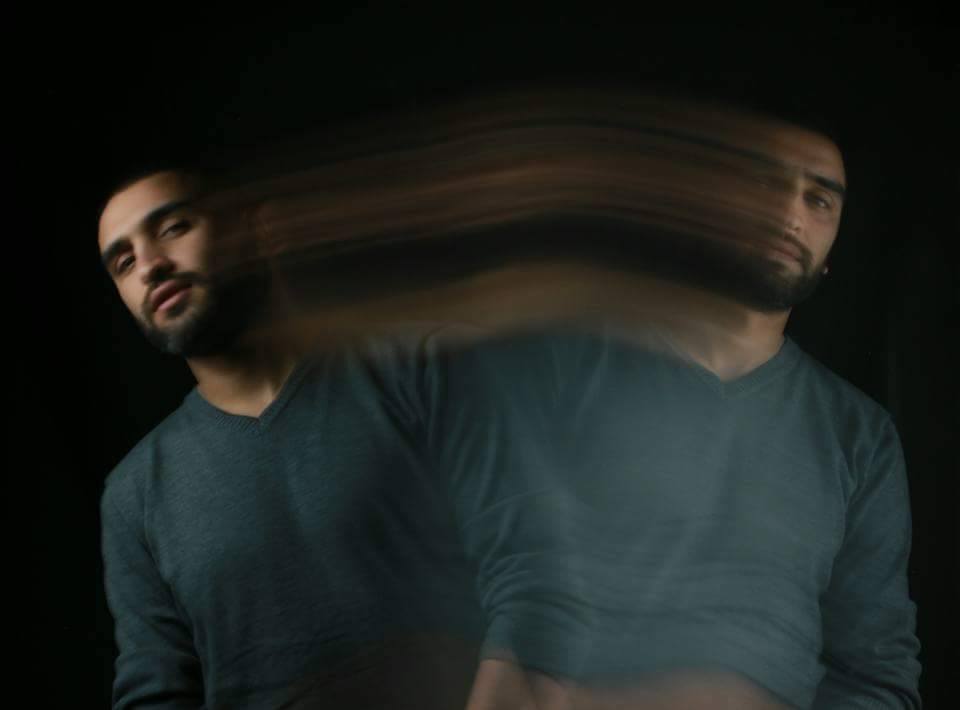

It turned out that I am a photographer and I cannot refrain from taking photos. And the demand to say it was so great, that I wanted to convey it to others. For me it was necessary to say it and relax. It is very difficult, in reality post-war recovery is necessary. After all of that the senses are very acute.

The human factor

In those days the first photos taken from Karabakh were mine, how the shell exploded, how one of the twin brothers died and the other was wounded, and another boy was wounded. Until the morning was gone, I took photos. It was terrible. On our street tanks passed by for more than an hour, they were all coming and going on our street. The camera was in my hand, but I did not take photos, because I did not know what was going to happen, if my photos would help, or harm.

When I heard about the situation with the children, I went to take photos. It became clear that the uncle of one of the children was my acquaintance, I did not take photos. When they took the children out of the operating room and said that everything was normal, then I took photos. Perhaps this is one of the drawbacks in terms of professionalism, but I considered the human factor as priority. To not harm.

To remain human

The first rule is to be a man. It is important that they trust you. If they trust you, you are already able to also take photos. In order to stay safe you must take into account all of the characteristics of war: the sounds, the shots. Those can be so shocking that you are not able to do anything.

The weather conditions must also be taken into account: the cold, the mud. You must be prepared for everything (to be cold, to eat anything, to sleep anywhere).

A person smiles when they take a photo of him. In the state of war it is also like that. The photographer does not have time to dig deep into people’s lives. And people, other than smiling, cannot give anything else to the photographer. Mutual trust is hard-earned.

Before taking a photo you must ask permission, and after taking a photo you must ask whether you can use the photo or not. I have asked the boys, they were even excited, because there they are in need of warmth, love, and attention, that for days on end they will not receive.

Areg Balayan’s photographs will be exhibited in the Mirzoyan Library until February 15, 2017.

Sara Khojoyan