Armen Shekoyan spoke about his time in such a way that that time he saw himself, found it and was satisfied. Just so, he was satisfied, because Armen Shekoyan took the most valuable step, reinterpreted the language in which we talk about time, liberalized it and once again made it come alive. And together with the language, all of us. Especially to the people of Yerevan and especially to the people of Yerevan who read newspapers.

It was proof of living liberalization that always begins with great writers.

For Shekoyan, language was a tool with which one can do many things: build, destroy, mock, provoke, inspire, excite, confuse. You can write a dedication, an article, a story, a script for a children’s program, a bureaucratic imitation or endless reflections. It does not matter what you write, the important thing is to write in such a way that honesty catches the eye and becomes a muscle.

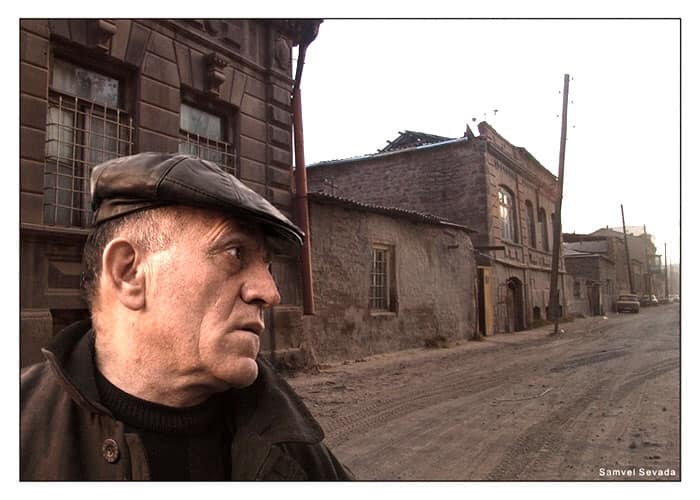

And Armen Shekoyan wrote in real language, boiling down the city jargon, etiquette and subtle self-irony to the maximum simplification.

“Now everyone says we should preserve our language, not realizing that it is a very bad slogan. Instead of saying, let’s develop our language, we say, let’s preserve it. After all, only dead things are embalmed and preserved,” he said in an interview, which he edited fifty times without exaggeration. He read, printed, edited, and read again.

“What? Did you think simple writing is easy?” he wondered.

Armen Shekoyan’s texts are always about the time when they were written: be prose (from stories to the endless novel flow of “Haykakan Zhamanak,” poetry, starting with “Yerevan” Hotel and “Anti Poetry” collections, ending with rhyming impromptu published in newspapers), journalistic columns or essays (one of the latest series is his authored column in media.am).

He eagerly combined the role of a documentarian with the role of an observer and intervener.

He was inventing the documentary (for example, attributing actions to real people, which they have never done, but according to Shekoyan, it would be better for them to do).

Perhaps, this is the ability that is most clearly seen in the greats, say, Parajanov. Both of them invented the present in such a way that there was no doubt that the present should be just like that.

Armen Shekoyan was most terrified that he could become a pedestal and lose his instinctive sense of being real. “I have always considered myself more valued than I should be,” he said. Of course, he was fishing for compliments a little, but only a little.

Of course, he wanted to do more.

For example, to become a song. He just dreamed that his poem would become a song and come to life, be heard from cafes and cars. And as a focal point, lose the author. In other words, enter among the people anonymously.

He was convinced that literary prizes should be given by ordinary readers. Even if it is wrong. He said that professionals misjudge more than lovers. If there were no lovers, there would be no good writers.

He often said that you should vote for the person you love. Vote for the writer, singer, politician you love. And without fear that you may be considered not very far-sighted, elegant or smart.

He always urged journalists to go to a press conference of a politician and write news in the newspaper, where what was said at the press conference be put in rhyme and take the form of a poem. He said, at least it will not be so boring.

He aimed not to allow poetry to suddenly become a serious mission and journalism a low genre. He used to say that no matter what you write, the important thing is to write well. And when I asked a thousand times what was good, he said a thousand times to not be false.

Reading Armen Shekoyan, and especially communicating with him, is one of the great pleasures that many will remember.

His deliberately ambitious and self-deprecating tone and at the same time his strict discipline (writing a certain amount of text daily so that the language tool does not suddenly rust or fade) is a very expensive legacy.

His humor glides through all the texts and sharpens the features of our time so that you always discover a new layer. A new wrinkle or a new scar. One round and a new wonderful formulation.

When he had the opportunity to publish his texts, he preferred the media of the day over literary magazines. He said that he wanted different things next to what he had written: sports, art, politics, weather forecast.

Armen Shekoyan was a network person, or rather, he wanted to be a horizontal network, to stretch, to branch out, to continue and, finally, to live like that.

Nune Hakhverdyan