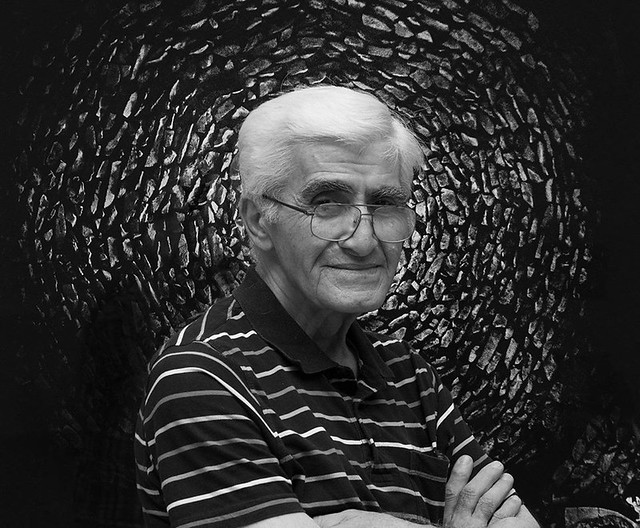

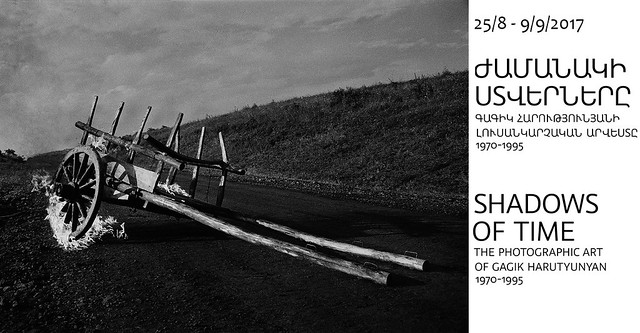

The exhibit Shadows of Time includes photographs taken between 1970 and 1995 by photographer Gagik Harutyunyan, which with thoroughly cultivated reprints and a conceptual arrangement become musings on the surprising turns of the path crossed and the time passed.

The exhibit organized with the joint efforts of Cultural Dialogue and Lusadaran Armenian Photography Foundation is considered a retrospective, but purely in the formal sense, since the word “retrospective” first of all means a view from here, from the position of today. That is, we look back because we want to understand the present. The interruption of this process is full of dangers and may become the beginning of public complexes. In any case, the Soviet layer of art and documentation is one such complex that is yet undefined.

Harutyunyan, who was active during the Soviet years, no doubt was connected to his time, ideology, and the idea of state commissions. But he found a redeeming formula that allowed him to do creative work, to create marginal imagery that transcended time and was close to the format of art.

“During the years that I worked at the paper, I would go to the regions of Armenia. The first few hours I would shoot for the newsroom, and then breathing freely, I would move on to free creative work,” he says.

Photographers are usually attachments — to journalists, media outlets, design, advertising. Almost all Soviet Armenian photographers worked for news outlets, and many remained there, as recorders of time. Few have been able to enter reality not only to record, but also to create a risky environment.

Perhaps that’s why self-contained photography exhibits are few in Armenia.

“I think it’s tied to a specific person’s personality. I myself at different years worked at Komsomolets and Lragir newspapers. To be honest, I didn’t like the work of a photojournalist, realizing that it doesn’t give me anything. You go to fulfill an order that you don’t care about, for example, leaders of manufacturing or agriculture…,” he says.

Documenting means to bear witness, but the issue is that surviving the test of history is he who finds openings and meaningful cracks in the documentation, being positioned as a creator.

Harutyunyan is sure: “You can invent something from anywhere, make, and get a good photograph. The photographer needs to be in motion because the photographic subject will never come to me by itself. I have to go, find that subject.”

And he went, waited, found, refined, and developed, and if it didn’t work out, he waited again or destroyed what didn’t work out.

On display at the exhibit were183 works from his enormous archive, all printed and processed in high quality.

Curator Vigen Galstyan assembled the exhibit with an internal rhythm. Or more precisely, a path. Viewers see not strings of images, but series arranged by ideas.

Shadows of Time is presented in series (Harutyunyan also worked like this): “Village Sketches,” “Karabakh,” “Tightrope,” “Tonir,” Old City,” and so on. As a result, appearing side-by-side are photographs that are unrelated in terms of time and space but are linked both ideologically and aesthetically. The series leave more of a research trail than of separate photographs. And it seems with their reluctance to speak they urge viewers to decode the hidden stories.

For example, next to Lake Sevan is an African beach, and the seashore is already seen as a way of life.

Whereas the 1988 “awakening” is presented with sit-in participants. Not awake, but sleeping demonstrators. Chosen were photographs where participants of the movement are unmoving, lying on the ground at daybreak, during a break.

Actually, to play within meanings is a very difficult and precious skill. To not lie, but to play. And because of this, Harutyunyan’s gaze seeks, say, the symbol of eternal rotation, the wheel, and turns it into a stone monument, just as in the 1990s, Karabakh’s natural course had turned to stone and time had stood still.

Or he finds that viewpoint when a fragment of a wall says more than a series of walls.

Walking on a village street is a man wearing a tonir like a dress. A woman with a concentrated expression on her face is sweeping the mountains, which without that act would definitely be sadder. A boy is walking, hanging from his neck a mirrored wardrobe door, on which the sun is reflected, and it turns out that the sun shines as long as the boy is moving.

The beauty of Harutyunyan’s work is that he leaves the interpretation of his photographs and the shift of contexts up to the viewer.

Series titles are as simple as possible: “Cloud,” “Puddle”… These titles that are purely illustrative and seemingly nothing remarkable concentrate the viewer’s gaze more on the image itself. It’s as though it is said there’s no secret, the secret itself is this moment in time. And it’s no coincidence that written beneath many of the images is “Untitled.” That is, seek neither information nor a decoding key outside the frame. Simply look, the key will appear by itself…

He titles Edmon Avetyan’s portrait “The Metaphysical,” while Hamo Sahyanin’s is “The Poet.”

In one photograph, Lenin’s statue is firmly standing on the pedestal but depicted from an unexpected angle, while in another image, the position is predictable, but it’s the statue itself that’s unexpected — already fragmented, without a head and without its pedestal.

Meanings are often very quickly perceived, and the exact details of time are not needed; what is needed is just to have your eyes (and your heart) wide open — as they say, catch the shadow and try to reconstruct the object and its environment.

For example, it makes no difference who are the people (also children) standing densely behind a cage-like fence, who with a fixed gaze are looking in an unknown direction; what’s important is the effect of the image. They are the participants of a peaceful and luminous myrrh-blessing ceremony in 1981 in Etchmiadzin Cathedral. But they could’ve been in a completely different venue and in a completely different time.

Harutyunyan hunts the rays and jets of light that are reflected on various surfaces, waft through the curtains, slip through a tunnel or dungeon, spread out on a throne. And these photos are closer to works of art, as an attempt is made to do away with the familiar form and observe a new form. For example, to wait for Goris to be covered in fog so that the caves in the distance appear in a new form.

Many of his photographs visualize the idea that an entire universe can be hidden in a grain of sand, twilight can be hidden in a puddle, or in an enlarged detail of a bell tower, which has been magnified so much that it no longer has any connection to the original form of the bell tower. The detail becomes more expressive than the original object.

It’s as though the objects are on the stage. For example, mountains cut across the image, and Garni’s temple appears backstage. The clouds come down to the gorge, separating the sky from the earth.

From the shots it becomes clear how meticulously Harutyunyan worked. For example, he approached a puddle several times and tried to find the best time to shoot, when the water level will make the reflection of the sun’s rays that he needed possible. The photographer was even prepared to bring water with him and interfere in the natural course of things, but fortunately, there was no need for that…

Harutyunyan not only documented the facts, but also polished a fact so much (cultivating a shot again and again, changing it conceptually, overturning the top and bottom) that it becomes not a “naked” fact but a meditation of a fact.

In the magazine Garun, for example, Harutyunyan made the photo a full and equal part of the text: not an illustration, but a thought.

“What’s important for me is that something be said. To give the viewer something. When art gives nothing to the viewer, doesn’t awaken the mind and emotion, it’s not needed,” he says.

Galstyan’s and Harutyunyan’s negotiations took six years. Initially, Harutyunyan refused the idea of an exhibit. Perhaps he wasn’t sure how his works would be accepted.

“At first, I didn’t want to do an exhibit, but now I’m very pleased. I think it was the right time, since my generation had to leave a little bit, while the coming generation had to be educated, rise up a little bit,” he says.

The fast pace of life doesn’t leave time to process information; the meaning escapes, becomes fragmented, muddled. It’s as though effort is needed to easily and leisurely savor what is seen by the eye, and moreover, to make what another’s eye has seen yours.

Harutyunyan comments on the rapid speed of time very interestingly. During the exhibit, sitting in the café adjacent to the Union of Artists [where the exhibit was held], he interacted with visitors — as an observer.

“Nevertheless, life goes on… It doesn’t change, perhaps we change. Sometimes I would get angry, seeing the conduct of some young people. To tell you the truth, I often wouldn’t leave the house. But after the exhibit I saw such young faces that I saw in the 60s, the years of the ‘thaw.’ Believe me, they were the same faces. It’s like the wheel has turned again, time has gone back, and man has been born again. I don’t personally believe in the idea of reincarnation, but it seems that’s the process that took place.”

”Now everyone takes photos and plenty of them. The abundance of photos, even the explosion (10% of all the world’s photos were shot in the last year) began from the affordability of photographic equipment.”

“Yes, photography is very affordable. And it make no difference, the times. In the 60s, when I was a teenager, photographing was also easy and affordable. Now not only taking photos is widespread, but also its distribution is easy. Yes, the photos are many and everyone takes photos… eh, let them photograph, there will come a time when they’ll feel that the quality of their work is higher or lower than the others’. The benchmarks will come later, as it happens in all areas. In Armenia, after the revolution everyone was involved in trade. I remember in the 90s there was a boom in shoes: everyone made shoes. Then came the boom of jewelry: everyone was sending their kids to study jewelry-making. And today, it’s probably the boom of photography…,” says Harutyunyan.

Photography has an astonishing role. It always claims to be the reflection of the original, of reality, but at the same time it is never perceived as a full and original reality in its own right.

Greatly contributing to the perception of this role is Gagik Harutyunyan, whose cultivated images that have passed through several filters become the shadow of time. A shadow that is more interesting when you try to guess the original through a shadow.

Nune Hakhverdyan

The views expressed in the column are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the views of Media.am.

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.