It’s not possible to imagine the history of the Armenian Genocide without the history of the media — like vessels of communication, they are interconnected and intertwined topics.

The Armenian Genocide in International Media

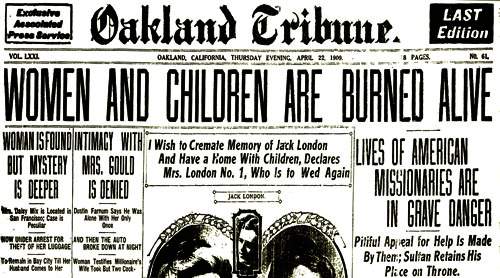

The topic of the Armenian Genocide was in the front pages of global media from day one, and when writing or talking about the genocide, this enables us to contend that we don’t need to prove anything — we simply show that which the world wrote about us at the end of the 19th century… and continues to write today.

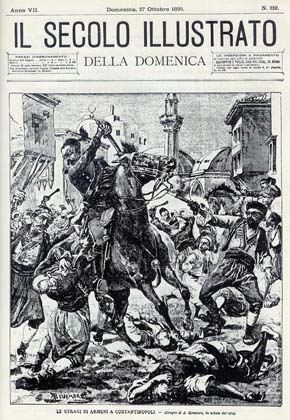

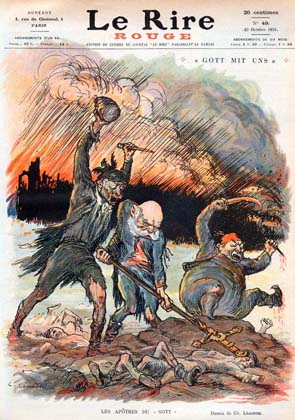

Prints (engravings) and cartoons made the history visible and, prior to the widespread use of photography, became a source of information.

When speaking about foreign newspapers, we mainly cite The New York Times (between1915–1918, the paper often covered the oppression and rights abuses of and violence against Armenians), but these topics were discussed globally, even in remote provincial newspapers.

For example, nearly all small US newspapers reported on the Armenians and the repression happening in Muslim countries.

The Armenian provincial press (the Constantinople newspapers less so) also contains an enormous amount of research material, as the Armenian press experienced rapid growth at the start of the 20th century.

During WWI, newspapers became tools of propaganda. European countries also printed and sent to the front millions of pamphlets, which depicted the historical episodes.

Those pamphlets, it can be said, assumed the role of the internet today, since they were distributed to soldiers, who wrote letters and sent them home, as a result of which they were made available to the masses and circulated around the world. It was also a time when caricature and [political] cartoons flourished.

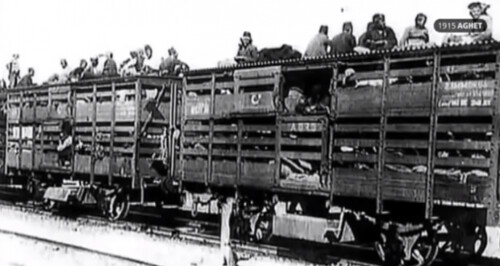

Then photography emerged, as documentary evidence. The newspaper Armyanski Vestnik, printed in Tiflis (modern-day Tbilisi), played a huge role, which began to collect and print photos of the genocide. And many of these today are the most famous photos of the genocide. Military photojournalists also made a huge contribution, and the legacy they left is still not examined in its entirety.

The newspapers became a source summarizing the memoirs and opinions of witnesses. For example, Morgenthau began to print his memoirs in a newspaper, later turning them into a book.

Certain periods of Armenian Genocide coverage in the global media can be identified: The active coverage phase ended in the 1920s, the sharp decline in coverage occurring solely due to geopolitical reasons (after the war, there were reforms, new states were created).

The topic was again circulated in the 1940s, when the massacres of the Jews began, and people were trying to find connections and precedents in history. The next revival was in the 1960s.

Now it can be said that the Armenian Genocide has a steady presence in the international media — at least 10 serious articles are published annually in reputable newspapers. In many cases, this happens due to personal initiative. Naturally, there will be many more articles this year.

How to Write About the Armenian Genocide?

First of all, we need to specify and divide the audience, since different emphases need to be made for Armenian versus foreign audiences. In many cases, we mix the recipients, which is why we don’t reach the desirable result. Let us agree that the world today is no longer terrified of victims and corpses, since the media now is awash with such images by the gigabytes.

And in those cases when text written for an Armenian audience is automatically translated and published into other languages, the effect, as a rule, is zero.

The topic of the Armenian Genocide has a huge educational role for an Armenian audience, as it helps us to visualize and understand our homeland, the true picture of which we often don’t know.

- Calling Western Armenia “paradise,” we have difficulty distinguishing, for example, Tigranakert from Kharberd. Meanwhile, the various cities were unique and very different from each other.

Moreover, we picture our homeland without any people, which is why we need to remind, familiarize, and present to ourselves the customs, culture, and everyday life of our ancestors, and the appearance and rhythm of their cities.

I would recommend we search for new stories about Western Armenian life. To remind ourselves about those who studied, became educated, built, and struggled. Let us not forget that in the Ottoman Empire, there was a modern, civilized Armenian society, and we are its descendants.

-

The history of the Armenian Genocide is also the history of the nation’s heroism, perseverance, and determination to fight. It’s a myth, that we were slaughtered like sheep. They fought in almost all the residential areas and villages; examples of heroism and resistance are manifold.

In the Holocaust, there were few examples of physical resistance. The Jews introduced the term “spiritual resistance,” spreading instances of small, individual resistance (examples of uniting in concentration camps or teaching children to read and write under difficult conditions).

There are many such compelling episodes in our history.

And let us also not forget the unique fact in world history that a nation which experienced genocide was able to create a state in only a few short years (in 1918). The massacres continued in Western Armenia, but the nation rebuilt a state. It’s difficult to imagine a more inspiring fact.

The Defense of Van

- Let’s try to move the topic from the emotional to the analytical, conscious sphere — to ask questions and find answers, including experts and intellectuals in the discussion. It’s hard to find material that examines the reasons for the genocide.

At the start of the century, there were already extreme conditions, but how come the public wasn’t prepared for them? Until we find the answers, we can’t impose the same of the rest of the world. Let us also remember that anyone has the potential to kill, which is sometimes aroused in the task of “saving the nation”.

Evil is gradually turned into everyday routine, and often it’s hard to grasp the transition, but it always needs to be analyzed.

- It’s very important to properly assess the material published in the foreign press.

There is always the demand to get information out to a foreign audience. We don’t have a lot of resources, and we all have to talk and write about it — and on all platforms. No one’s going to do this for us. Especially since social networking sites allow us asymmetric actions.

- Depict Armenian civilization at the start of the century. And as evidence of a crime against humanity, speak about the collapse of Armenian civilization. Armenians’ desire to live in dignity and evolve is a fundamental human right, which was trampled upon in the Ottoman Empire.

- And the articles can be constructed from that (human rights protection) perspective. The educational level of Armenians, the issue of women’s equality, and the great achievements in science, arts, and sports can be mentioned.

- The history of the Armenian Genocide must be placed within the context of local memory. So that the history doesn’t seem alien to the international community, connections with the world must be found. Present the genocide through foreign missionaries, teachers, diplomats, and others who are known in their countries.

For example, Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross who is worshipped in the US, came to Istanbul when she was 80, to help the Armenian children. Though her, bridges between the US Embassy in Armenia and the Armenian Genocide were forged.

- Place the Armenian Genocide in the global context. Draw parallels with other crimes against humanity — especially the Holocaust. When writing or talking about the Armenian Genocide, don’t use the word “tragedy”. The genocide is not a tragedy; it’s a crime, and one that remains unpunished.

People were killed, property was seized, a civilization was destroyed, and the thieves and murderers have yet to be punished, while the accomplices have not been called to account. A case was opened, a trial took place, the guilty were determined, but the case isn’t closed. It remains open.

We shouldn’t ask to remember the genocide. We should demand that different bodies pursue the goal of bringing the crime to its logical conclusion.

-

It’s better to move away from simple numbers and focus on individual human stories. Numbers are not as powerful as specific human fates. The story of Aurora (Arshaluys) Mardiganian is the best evidence of this. This young girl is quite a symbolic figure for retelling the Armenian Genocide.

There are three prerequisites to committing genocide: participants, survivors, and the criminally indifferent. Healthy and progressive is the society where the number of the criminally indifferent is few. After all, the long-term goal of any media attention is that: reducing the number of the criminally indifferent.

Suren Manukyan

Deputy Director of the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute

The views expressed in the column are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the views of Media.am.

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.