Was conflict reporting difficult during your time or now?

War is a place for serious pondering, thinking for journalists. And I’ve never understood what “difficult” means. It either has to be interesting for the journalist or not: what’s there to be difficult? If it’s interesting, it’s not difficult. If it’s not interesting, that’s when it’s difficult.

To capture a key moment or help the injured person beside you: in this dilemma, what do you do?

Definitely help. Is there any doubt? A person is unwell, and I continue to film? Can I? What’s a key moment? There’s nothing more important than a person’s life.

In the early 90s, why did you go to the frontline, because you were working at the TV station in Stepanakert?

At the time, everything was frontline. There was no “secondary line”. Our TV station’s boys, for example, would go to Shahumyan [alternative spelling: Shaumyan] — to fight. No matter how you go, it becomes the frontline; there was no other kind of fighting.

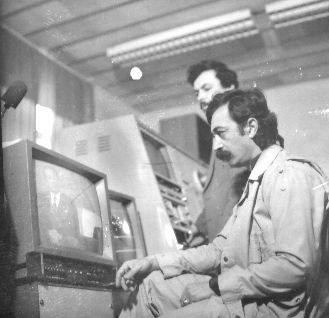

Filmmaker, Yerevan State Institute of Theatre and Cinematography lecturer Nikolay Davtyan is one of the older generation’s documentarians of the Karabakh War: with colleagues, he founded the Armenian Ministry of Defense’s Documentary Film Studio.

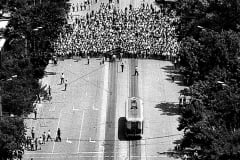

In February 1988, he began working at the TV station in Stepanakert, and with camera operator Gagik Simonyan and cinematographer Gagik Mkrtchyan, recorded also the history of Artsakh’s independence, beginning from the first rallies in Stepanakert.

I read in an interview with you that the Stepanakert TV station’s building was bombed or exploded in 1991. Will you tell us the details? Did the Soviet army do it?

I don’t know — it’s hard to tell who did it. I even think perhaps it was our guys. It was a very interesting juncture at the time: Karabakh was living beneath three flags — Armenia’s, Azerbaijan’s, and it had its own flag. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, there was a fourth too. [Karabakh] was governed by a special administration committee led by Arkady Volsky, and there was the spetsnaz [special forces], which stood in Stepanakert’s main square and everywhere.

And the spetsnaz had blocked the entrance to the radio station, giving Azerbaijanis an opportunity for propaganda. They did that propaganda very sloppily, but no one could prevent it. But after the explosion, that ended basically. There were no victims: it was around 5–6 am, but the studio disappeared. Only the first floor, the radio floor, had been damaged, while on the second, television floor, we continued to work, do our broadcasts.

I read in the same interview [AM] given to Kinoashkharh that in the [TV] programs you even tried to teach people how to make grenades…

Yes. Because at the time life in Karabakh was unpredictable: you’re sleeping at home at night, they could enter your house… our propaganda, of course, yielded results — after all, how did people become armed?

They had self-made guns; everyone invented something, made something.

Didn’t the special administration authorities punish [you] for such programs?

Volsky was a very interesting man: he was the commandant of that time. He would say, I know everything, don’t do it, but he wouldn’t take any drastic steps. For example, when the radio shut down, our technicians from Yerevan explained that there’s another system, a city, wired radio, which you could broadcast from Stepanakart by connecting to any place on the line. We began to make use of this. The special administration committee understood quite well, they came every day and said, it seemed to be your voice coming from the radio… I denied it of course, and they didn’t come after us too much.

At the time, that radio was very much in vogue, everyone was listening to it, and it wasn’t possible to stop it. You connect, say, the recorder, with a taped program, from the roof of any building, and on which building it’s connected, go try and guess.

When your generation was documenting the war, did you record and disseminate bloody images or images of the dead?

We didn’t disseminate them. Sometimes it was necessary to film, but we didn’t use it. In one film of ours, there are scenes depicting how the dead are transported on horses, but you can’t see them in the scenes that were used, they’re wrapped in clothes.

You were asking whether there was something in the coverage of this

four-day war that angered me. I’ll say now that there was — it was the brutal images. They shouldn’t have, it was terrible.There is a justification: we had to show the world that look, the opponent has committed such inhumane acts.

The world, that is, for which authoritative body it was needed, show them, but don’t publish them. And the international community, isn’t it clear, what it always says, and doesn’t judge at all with images? We shouldn’t disseminate the savagery — even without it, the face of war is awful. Fighting is not a good thing; it’s a very bad thing. I’ll film a house that was shot at, a destroyed house, but I won’t film a person who was tortured. Or, if I’m the only one, and it’s a very important fact, I will record it, but I won’t publish it.

And what would you say about the propaganda journalism of those four days of war and the days that followed?

Well, propaganda, to be honest, I don’t understand what it is. The ‘most correct’ propaganda Edik Baghdasaryan is doing. The formula? To show without needless emotions, nor to ask “give me 100 likes”. Well he’s experienced, he knows very well what to do.

Almost all the documentarians of the war that time were uniformed and armed; they received a military rank. You were an officer.

Yes, I received that rank while working in the ministry’s studio. It was by working there that we could go to the battlefield. With our work trips in Artsakh we would enter the defense army’s office, at the time, Seyran Ohanyan’s office, he would give written notice that these people have the right to go to these and these zones and participate in commanders’ consultations.

But today, I don’t think there’s a need to go to the frontline. Today, there’s no problem to take a close-up shot, today there’s a different war: all this is long-lasting, it’s much more long-lasting. Today you have to be more careful.

And not with a military outfit.

Of course. A civilian has no right to wear a military uniform, especially with epaulettes: during the Communists’ time, you would go to trial for this. But today they sell that uniform in Yerevan’s Vernissage [outdoor flea market], you can buy it, wear it, and go to the front. I recently went to Stepanakert, to film the delivery of 16 vehicles brought from Sochi as a gift. But if I needed to film on the frontline, all the same, I wouldn’t wear a military uniform.

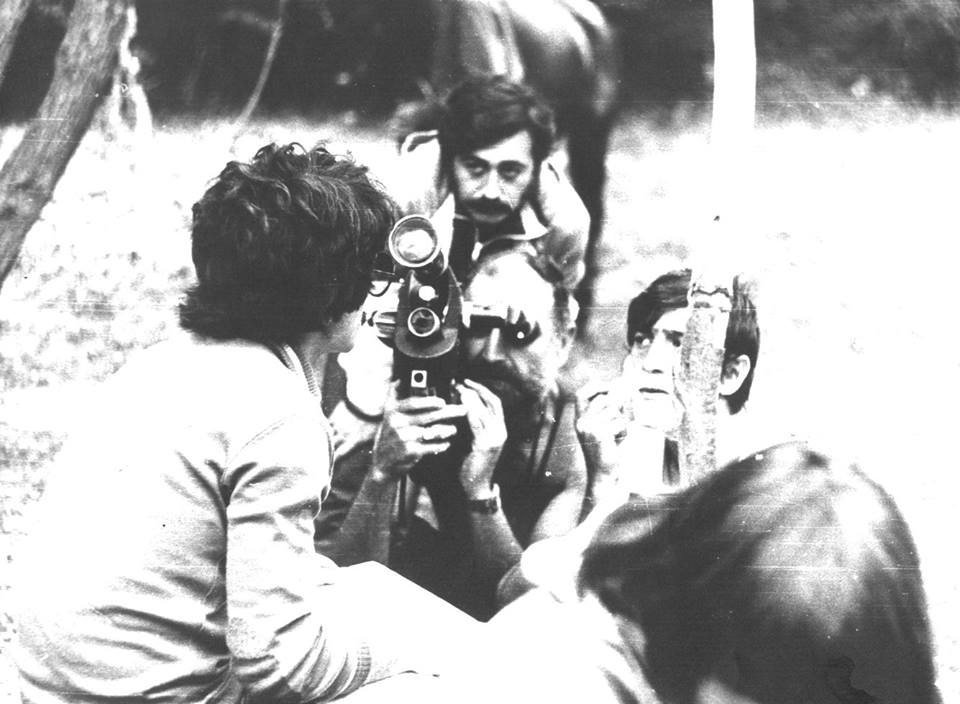

Those days, yes, we were considered military, we had weapons, and when needed, we would shoot. My camera operator didn’t have a weapon. When Tigran Gevorgyan was filming, I, standing with my back, holding a weapon, would follow. One time they suddenly began to shoot from the bushes, we all got up, and began to fire back in that direction.

And were you obliged to obey military orders?

They didn’t give us military orders. Even with [Army General] Manvel [Grigoryan], whose strictness many spoke about, we would do our job.

And if there was an order to retreat, could you not obey it (let me hide here, film)?

No, we weren’t stupid [to] hide under a bush and film. That’s already a war command; if everyone’s going, you remain there defenseless and do what? We were shooting a film with Gnel Nalbandyan, it was called “Don’t Diverge From the Path”. It was about combat engineers. The bodies of seven of our boys had remained in the territory where we no longer had troops. Gnel, Tigran Gevorgyan, and I went back with the detachment to bring [the bodies]. You enter a village where our troops don’t reach, you’re defenseless. We were lucky that we didn’t come across anyone. It may be that there was not a single Azerbaijani, but it was like playing a game of war: you go, you hide, and you go again.

Do you have tips for beginner war zone documentarians?

You shouldn’t be ashamed of fear. Fear is a very natural thing. From the very first day you begin to guess where an approaching shell will fall approximately.

When you’re in an open field, you shouldn’t run this or that way. The right thing to do is immediately lie down on the ground, tightly covering your ears with your hands. Also, I can’t imagine it now without a helmet.

In the photos from those years, you’re bareheaded.

There were no helmets during our time. We received some American helmets — they were made of plastic. It was a little comical… Because it was [part of] an American police uniform. Well, probably the police manages with plastic helmets. By the way, they would give them specially to our officer staff: there were shoes, trousers, jackets, glasses… everything.

[In September 1991, Associated Press writer Mort Rosenblum described Shahumyan’s Armenian detachments as follows: “Fierce in battle, raucous at rest, they look like a mixture of World War II partisans, medieval knights and Gilbert and Sullivan characters outfitted from a U.N. flea market.”

In those detachments Rosenblum saw both teenagers and “grandfathers” who wore whatever they found: parts of Soviet uniforms with running shoes, bright green burlap with NATO adornments, white baseball caps or helmets. Most wore gold crosses… (The report summary was published in the Sept. 5, 1991 issue of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)].

What about creative tips for war documenting beginners?

I’ve filmed war for all these years, today someone tells me, I saw a shot which you were in. I don’t know who filmed it. When the journalist can be seen in the frame, I don’t like it. When you watch a film, that’s something else, [but] I don’t like it in journalism. I don’t know, irrelevant or meaningless stand-ups make me angry. While I was shooting the film, when they were firing [on us], this poor Gnel was forced every second to hide from the shells. And that’s how I filmed it.

Don’t you see your footage now in the most unexpected various places?

I do, and it makes me happy. If it’s needed, please, let them use it.

There’s a scene that Tigran and I shot: about the war. There probably isn’t a film in which that shot doesn’t appear. It’s a tank attack: one after the other, tanks are coming out of the bushes, firing. There are other such shots, let them screen them, I would only be happy.

Interview by Ruzanna Khachatrian.