For the past several years, artist and curator Ruben Arevshatyan has been working on an extensive research project called Sweet 60s, which aims to gather and reinterpret the archive of images of the most interesting and contradictory decade of the 20th century.

Exhibitions and conferences are being held in various corners of the world to present this multi-layered period of history. Recently published, an extensive catalogue of architectural projects called Soviet Modernism features the guesthouse of the Armenian Writers’ Union at Lake Sevan, as the best symbol of the modernist structure, on the jacket.

Sweet 60s is structured like an archive: one can view the photos and the projects, and become acquainted and establish a link with architects from different countries. It’s a database, the visitors of which do independent work, studying the images and documents.

Arevshatyan notices that many problems today began decades ago, since the transformations taking place in public space haven’t yet been ratified.

In a surprising coincidence, problems in architecture and the media in Armenia today are developing practically the same way. Television (as well as public space) is becoming privatized, though it continues to fulfill a public function. Born from this ambiguous situation are manipulations, and it becomes important in whose hand the tool to carry out public functions is.

Many of the buildings in Armenia have become a memory. Even 20–30-year-old buildings (not to mention those from the previous century) are recalled with nostalgia. Is memory overshadowing the present?

The desire to remember is not nostalgia. The nature, the reason for that longing is more so tied to unresolved issues. It was very interesting, for example, to observe public reaction when it became known that the embodiment of the value system, say, Moscow Cinema open-air hall or Mashtots Park was being taken away from society. Something familiar was being taken away and replaced with a completely different value system.

I think, in that sense, the 60s are very instructive. They put forward a new state, new possibilities, and many questions. Wars, revolutions, and the crisis forced issues previously put forward since development to be transformed and to become repressive systems. The idea (which, by the way, was often quite progressive) remained, while the initial project and its implementation contradicted each other.

|

“The fields of new media, social networks, are tools where an intensive discourse is taking place. That is, someone’s remark immediately gets a response, is subject to criticism”

|

Society was wrestling, pushing technological modernization forward. Parallel to this was the experience of two world wars, which showed that modernist principles also contain dehumanizing elements. The method, the technology, had begun to work against man.

Architecture reveals this brilliantly, since it’s always been able to express both the emerging trends in society and the correlation between the ruling authorities and public processes.

Architecture best expresses public utopias, which, after all, are the main propeller, the horizon, the vision that shows where you’re going, where you’re directing your view. Utopia is that necessity which has disappeared over the last 20 years in a global sense.

Are we short-sighted in our thinking?

Thinking has become fatalistic, which is the result of crises and unresolved problems. It was in the 60s that we put forward a feeling of utopias and despair and disappointment. It’s amazing, but those constructs are the same also today.

What explains the fact that the buildings [in Yerevan] that have disappeared or on the brink of disappearing are those that primarily have a public function — cinema theatres, parks, pedestrian crossings, and so on?

The understanding of what’s public has changed. Arisen is a paradoxical attitude where there is, on the one hand, a basic understanding of the need for public space, while, on the other hand, an opposing view, that the equal distribution of public good is simply not possible.

Go into any [residential] courtyard [in Yerevan] and you will see how public space is being fragmented. And, by the way, it’s not an order from [the ruling authorities] above — it is the public itself that is beginning to privatize that which is public.

And the problem is not just about “tearing away” space; the perception of what’s public is changing (space cannot simultaneously belong to everyone and be tended to by everyone equally).

Based on this idea, city authorities, the oligarchy, speculate quite well, saying, see what state public space has come to; it’s better to privatize it, so that it begins to (supposedly) blossom, to flourish.

But actually, in several instances we see that the city is losing its public spaces. And this loss is expressed even in caricature-like ways.

Architecture and the media, it seems, have the same problems. Many of the TV channels are privately-owned but fulfill a public function. It’s the same with space that has public significance (but is privatized).

The media is a serious tool, and first of all, it has to viewed in whose hands it is. Let me cite an example: years ago, when it became known that Van Khachatur’s geometric abstract design on the wall next to Ani Plaza Hotel was to be covered up, there was a serious backlash. Holes had already been dug up and the wall was being torn down when Van Khachatur declared a real battle to save his work.

|

“After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the entire KGB culture began to develop quite tendentiously and take root particularly in the TV sector” |

The media played a very interesting role in this struggle. The TV channel Prometheus at the time (present-day h2) prepared a video report that graphically showed the hotel’s front slowly being covered and a new, clean one being put up in its place.

That video was a very important mechanism that showed how the media (purely as a tool) works on changing public consciousness. It does so gradually. The same way as, say, a certain businessman MP is now demolishing the Pak Shuka [the famous closed marketplace on Mashtots Ave.].

The transformation of the Pak Shuka occurred like so: bulldozers actively began to destroy the building particularly during the New Year’s holidays, when people’s attention was focused on completely different things. The media also works with this mechanism — consistently and gradually acclimatizing you to the idea of change. That’s how h2 acted: by creating an illusion for the audience that it had already seen the image of the hotel wall — without the artist’s work.

Man, in general, is guided by images. When, say, architectural images disappear, he becomes acclimatized also to the lack of possibilities afforded by that architecture. When there’s no model, there’s also no prospect.

If there’s no cinema theatre [building], there’s also no cinema…?

I’ve studied this problem for a long time, and I can say that the situation in Yerevan still isn’t as terrible as in, say, Ashgabat [the capital of Turkmenistan], which had shining [examples of] modernist architecture, but now has nothing. Buildings have been either razed to the ground or covered in marble.

To a great extent, whoever does that (the authorities or private owners) always speaks from the position of public interest. They say, but you don’t like the Soviet past, and so I am eliminating that which you don’t like.

That is to say, everything is being done to show us that the Soviet [era] hasn’t been eliminated. The Soviet [past] very beautifully and smoothly continues; only one thing has disappeared — the vision of possibilities, the utopia. The rest is the same: the hierarchical system, and even the human typology.

There’s a very important fact: in the past, the political landscape assumed the existence of a horizon. But when your view is blocked with a few ugly buildings, you accept that as a fact. Or you exert efforts to climb up [the wall] and get a view from the highest point (until someone blocks your view once again).

Isn’t perhaps the definition of ‘public’ somewhat abstract and incomprehensible?

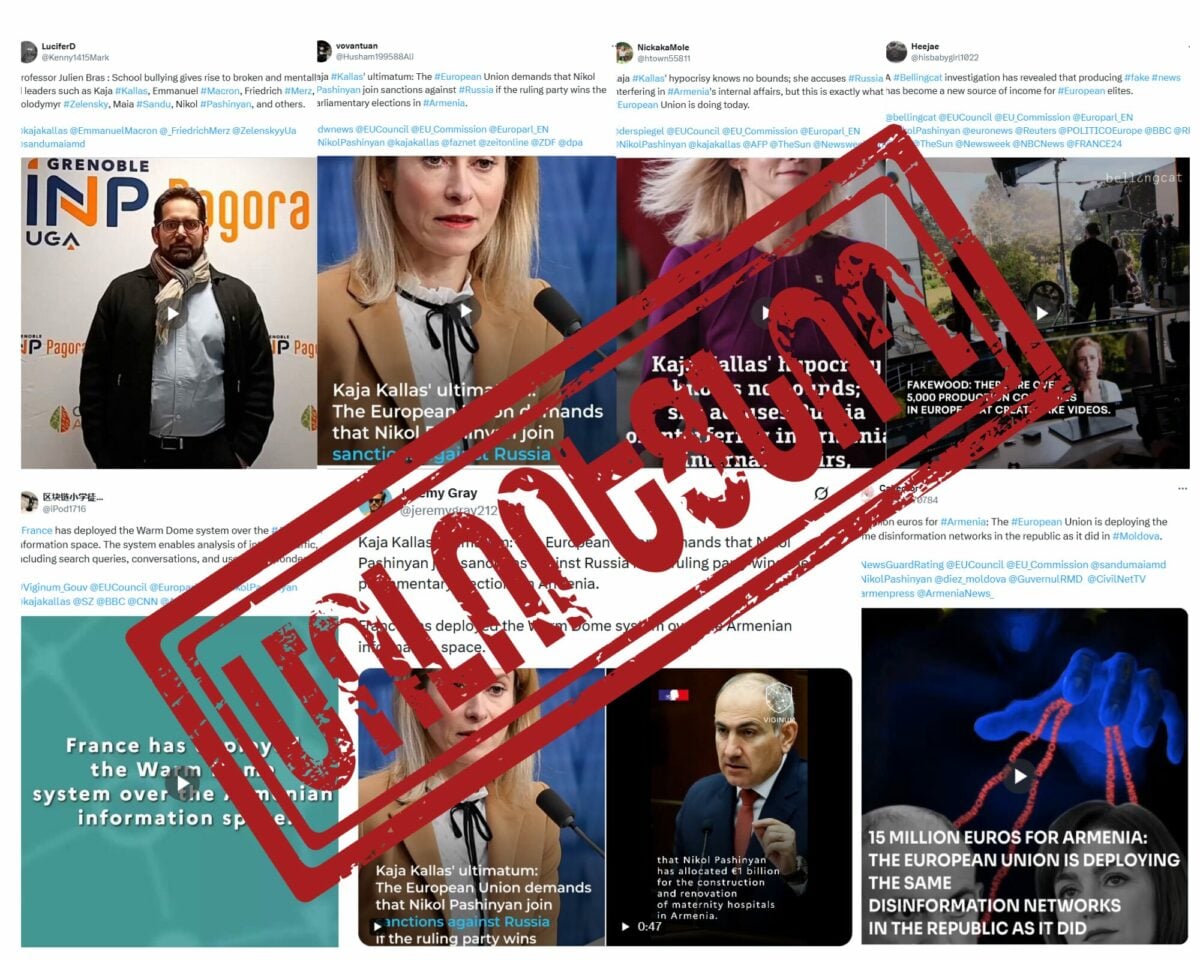

All constructs and notions, after all, are virtual projects. All have undergone particular development and crises, and some projects are very strongly ingrained in the public’s consciousness. Taking place within these projects is manipulation, where media plays a very strong role.

Of course, each person carries within himself skepticism for all types of structures and tries to review or resolve their role. He wants to understand why he’s in this difficult situation. The person, group or community above doesn’t want to lose control of the situation, and here is where manipulation comes in.

At the end of the day, all manipulations today (also in the media) are aimed at the very tendentious development of a consumer society. For this reason, finding the balance between the public and the individual is one of the most important issues today.

The authorities often cite media freedom as an achievement. It seems you can write or show just about anything…

That is said, primarily pointing not to one’s own remarks, but to what another wrote or said. That is, it is again the issue of a moderator. The conversation isn’t carried forward to the point of the supremacy of public interest.

In this sense, the media fulfills its function: it fills the time — it makes an event out of everything while simultaneously having the chance to manage the situation. See, what a magnificent picture: on television, a group of students come out against another group of students and begins to prove its own truth. And then the other group does the same. In the outcome, the message gets lost. And the media is full of such scenarios.

Ironic pragmatism feels quite at home particularly in television. Why?

When we speak of, say, the format of televised debates, we see it’s the same all over the world. Almost everywhere is the ironic rhetoric or a belief that there exists some meta-category, which governs the situation from above.

Usually when you begin to take something unduly seriously, a contrary, primarily ironic reaction begins. This is particular to popular folklore. Suddenly you see an unquestionable, unyielding idea appearing at an anecdotal level, and in a laconic, concise way, the exact opposite meaning is attributed to it. Humor rationalizes its deadlock situation. This is the critical view, which can deconstruct irreversible claims and “open up” the essence of the system.

|

“The media fulfills its function: it fills the time — it makes an event out of everything while simultaneously having the chance to manage the situation” |

I think, our ironic perspective has reached extremes and is expressed in the media industry with great intensity. For example, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the entire KGB culture began to develop quite tendentiously and take root particularly in the TV sector.

It’s no coincidence that the new president of the Council of Public Television [and Radio of Armenia] is a former KGB apparatchik. This means that the opposer, that bearer of ironic culture is becoming the ruling authority.

Now, new media dictates.

The fields of new media, social networks, are tools where an intensive discourse is taking place. That is, someone’s remark immediately gets a response, is subject to criticism. I can respond, asking for an explanation for each word or term [used]. It’s impossible to ignore or avoid explanation. And here, a new approach to ‘public’ appears.

The layers of the discourse are changing. In Armenia, for example, it was perceived that the public view is expressed by the intelligentsia. But now we see that this strata generally can’t say anything and has moved to a completely different field of discourse.

For me, the most interesting layer is comprised of civic initiatives, which not only bring new political currents, but also create many new tools.

People often stress that politics doesn’t interest them and they prefer to do their own, small thing.

That’s the logic of a neoliberal consumer society: the horizon is restricted by being shaped by a small, individualized world. When after the 70s consumer culture began to be intensely disseminated, the public rapidly became depoliticized.

The examples of this are everywhere (watch any Soviet film). In the media, for example, the number of “events” drastically increased (this obsession reigns all over the world), but we consume that amount. And just that — nothing else is required of us.

Welfare, well-being became the new utopia. And this welfare is the main noose that impels us to strive for the impossible.

Interview conducted by Nune Hakhverdyan.