Jacopo Ottaviani studied computer science before he partnered with renowned publications such as “Reuters,” “Spiegel,” and “Al-Jazeera.” Despite his technical background, he was deeply passionate about journalism and as he puts it, “in love with” it. His dream was to become an international magazine or newspaper reporter.

Jacopo, how did the transition from computer science to media and journalism happen, and what brought you to journalism?

I used to read books by Italian authors who wrote about traditional journalism during my time as a student. I dreamed of exploring the world and sharing my experiences through writing, just like them. After completing my university education, I realized that I could combine my technical education with my passion for journalism. I discovered that my technical knowledge could be a valuable asset in pursuing a career in journalism.

To be honest, I was also a little lucky. The time when I graduated coincided with the emergence of data journalism as a distinct branch in Italy. My technical skills and professional education perfectly aligned with data journalism. That’s why I am always grateful for my technical education.

You have been engaged in data journalism for 14 years. In your various posts, you have mentioned that data is a wonderful tool for understanding reality and influencing that reality. How does that tool work?

Absolutely! Data journalism is an incredible tool that can significantly impact public decision-making. In general, statistics have a significant influence on shaping public debates and discussions. Incorporating numerical data in your work can change the entire perspective. Digital data allows people to make informed decisions based on solid facts and analyses. This is what makes data journalism so powerful.

Handling data with great care and attention is essential, as there is a significant risk of manipulating the reader if one is even slightly negligent.

That problem especially arises in the case of wrongly chosen visualization, right?

Data journalism is a multidisciplinary field that involves several components. Communicating the extensive work done through a well-chosen and understandable visual representation is crucial. Without visualization, many people may find comprehending a large amount of data or numbers challenging. Therefore, we strive to make data journalism accessible and understandable to people from all walks of life.

But before making the data understandable for the reader, it is first necessary to find and acquire it. What if the data is not available?

Oh, that’s a serious problem. Sometimes it can be impossible to find the required data simply because they do not exist.

In such cases, the first step is to acknowledge the absence of the database related to the given topic or problem. The next step is to consider creating the database ourselves, if possible.

I’m sure you have faced such a problem over the years. How did you solve that equation with several unknowns?

Approximately seven years ago, we were working on a project and wanted to determine how many young individuals from Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Spain had traveled to other European countries. Since these countries belong to the Schengen zone, gathering accurate data regarding their travel destinations was challenging. To collect this information, we developed a questionnaire and asked people to fill it out and share their travel experiences.

Thousands of young people responded to our survey, and we used their stories and data to conduct an online investigation. In the article, we specified that the data were not factual and presented the data collection methodology.

Photo from Jacopo Ottaviani’s personal archive

From the point of view of data collection, you also carried out quite extensive work while implementing the international project The Migrants’ Files. What made this project special?

Yes, it was an international project that involved journalists from 15 European countries. Our goal was to understand the number of migrants who died while trying to migrate to Europe. This project was implemented approximately 10 years ago when no single unifying database that would provide the necessary information existed. As a result, each of the 15 participating journalists collected data from their respective countries. Later, we combined and completed the data to create an extensive database.

We used maps and other data visualization tools to represent the data we had gathered. Additionally, we published about 20-25 stories of individuals that were part of the project. This project had a significant impact and was recognized with an international award for data journalism.

Later, the database we created became available to the public as open source. It was also used as a source in the UN.

Your work is closely related to Africa, you lead the organization Code for Africa (CFA). How did you start?

After graduating from university, I applied to a company that helped young journalists implement innovative projects in countries of the Global South. I proposed a project in Mozambique about land rights.

During my three weeks in Mozambique, I had a life-changing experience. I witnessed firsthand the many positive developments taking place in Africa, yet nobody seemed to know about them. Following my involvement in several African projects, Code for Africa(CFA) approached me to create a data journalism program for them. This opportunity led me to join CFA, where I eventually became a manager due to my extensive experience working in Africa. The organization currently employs over 120 people and is engaged in various projects, including training African journalists. Additionally, CFA has a fact-checking and media monitoring team and conducts media research, including preparing Reuters reports for Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria.

What was the most challenging task you and your team undertook in Africa?

One of the most challenging projects we undertook was in Nigeria. We had to establish a new office focusing on forensic journalism projects, which was difficult. Data journalism is still a relatively new concept in Europe, let alone in African countries, where it is even more unfamiliar and complicated. However, despite facing many obstacles, I am happy to report that our team successfully implemented a project that even won an international award. The project was called MapMakoko, a mapping project of the Makoko area, and it can be considered one of our most successful endeavors.

The project that merged journalism and technology was implemented in Makoko, a neighborhood in Nigeria, Africa. The area was home to around 300,000 people living in extreme poverty. Neither Google Maps nor OpenStreetMap had a map of the settlement.

We decided to create that map using about 990 photos taken with drones. The data from those photos was made available on OpenStreetMap.

The data and statistics collected during a project were used for scientific research. Many media outlets, including CNN, covered the issue after the project was completed, and a documentary was made about the neighborhood. This project won the prestigious Sigma award in the field of data journalism. However, what’s most important is that the data journalism material turned into an urban planning and development program. This shows the significant impact of data journalism in changing phenomena and decisions.

Jacopo, this is your second visit to Armenia. Could you please tell us about the purpose of your visit?

Yes, this is my second visit to Armenia, at the invitation of the Media Initiatives Centre. As a data journalism trainer, I provide guidance and support to public organizations and editorial offices. I help them understand how to work with data and how to tell compelling stories using data. I conduct trainings on data journalism both in Italy and abroad.

Now we are working with Armenian journalists on a special project called “Documenting the Drama.”

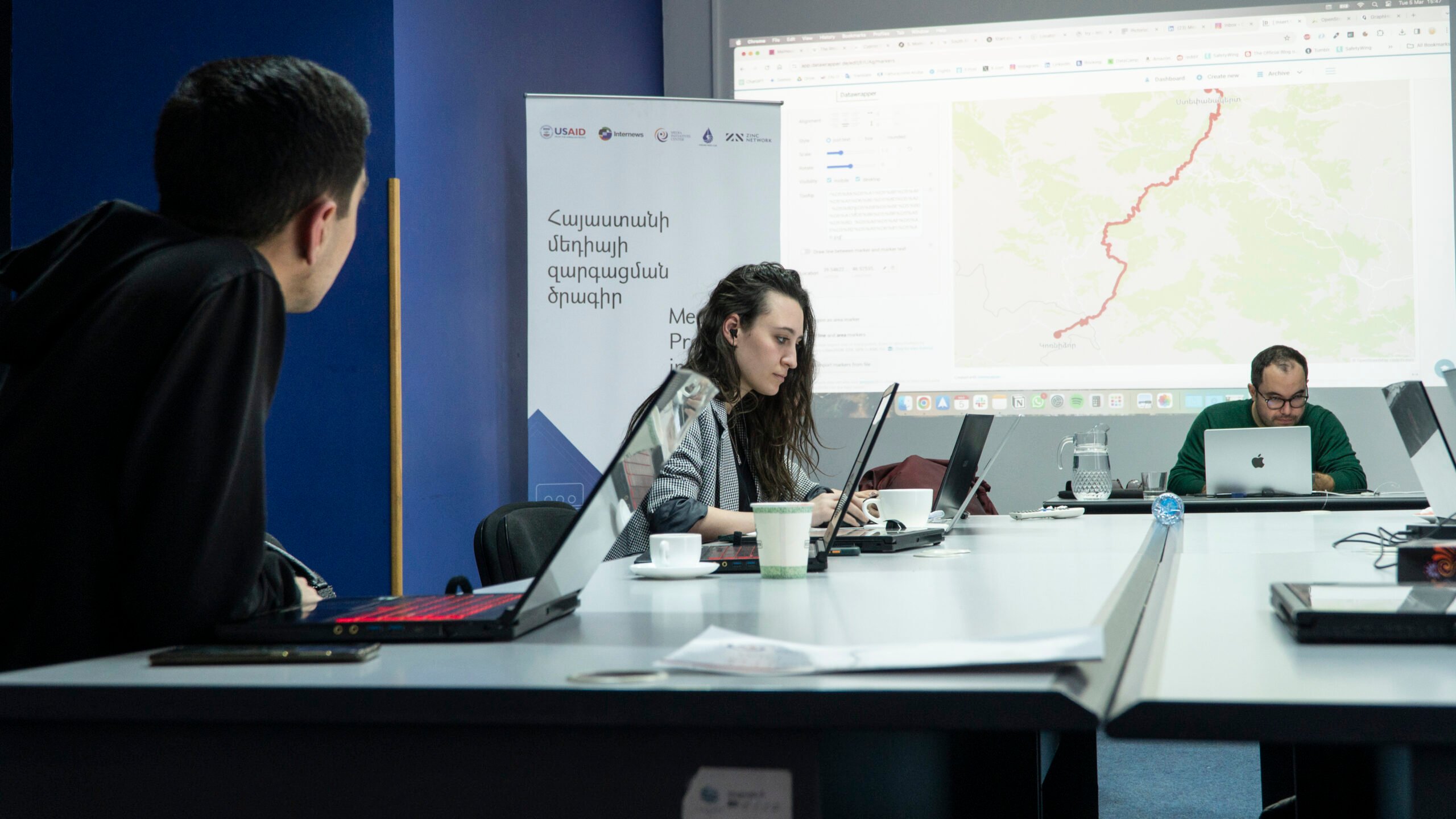

During the Documenting the Drama course

It will tell how the people of Artsakh managed to reach Kornidzor from Stepanakert. To present human stories, cases, and digital data, the journalist team will utilize special approaches and tools. All the data has been collected by the journalist team. During my three-day course, I assisted them in delivering their data and stories to their readers in the most accurate, descriptive, and interesting format possible.