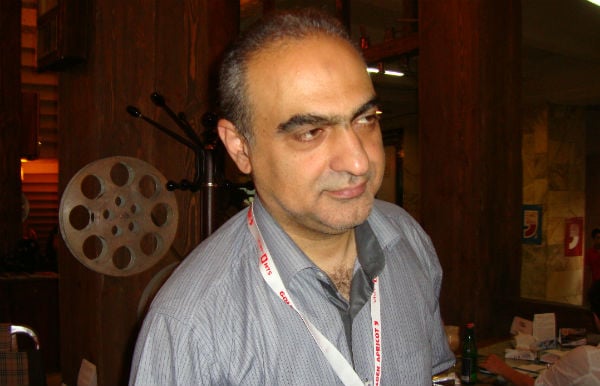

Iranian filmmaker Ahmad Reza Motamedi hasn’t shot a lot of films — he admits that teaching takes up a lot of his time. For 30 years he’s been teaching Islamic and Western philosophy and art history at the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB).

A scriptwriter, essayist, and author of scientific work, Motamedi has been working on a book for several years, which he hopes to have published before he dies. “When I was young, I rushed and quickly published several books, but now I don’t work like that. I allow the book to mature…”

Forgetting and faith are at the core of his film Alzheimer, which screened at this year’s Golden Apricot Yerevan International Film Festival. The main character in the film believes that her husband is alive, though consciously and according to the Mullah’s insistence this can’t be. The filmmaker is sure that a woman’s faith is beyond both scientific claims and religious faith. It is the inner conviction that a person carries in herself and completes her existence.

Motamedi is a philosopher of cinema who is convinced that cinematography is as powerful and comprehensive as poetry, where characters and the paths they’ve crossed (and the ones they have yet to cross) are not always visible. And in cinema, as in poetry, what’s important is what is not seen, since it’s in the unseen where the hidden magnetic power of art lies.

Iranian cinema is at once traditional and modern. Does it have an impact on the lives of Iranians?

Due to their genetic heritage and their work, Iranian filmmakers are able to create a connection between Iran and Iranians (as well as the world) — to get into conversation with the audience. But if we want to measure Iranian cinema’s impact on society in overall history, we would be convinced that it has left nearly no mark (unlike, say, Iranian poetry).

We don’t have a film that in its maturity is equal to Hafez’ poetry or to Persian miniature, which had an enormous impact on Persian art and was the origin of several variations of painting. Cubism, for example, was influenced by Persian miniature, where traditionally objects are drawn simultaneously from different angles and an image is created where all periods of time are intertwined.

Very close to my heart is Heidegger’s belief that we greatly undermine art today, since we reduce it just to the level of communication. We’ve forgotten that art is not only for creating connections between people; the mission of art is to create a language. And language is first and foremost poetry. In my opinion, in our life, as well as in cinema, there’s a great lack of poets. That gap is occupied by new media, the Internet. It’s unfortunate that mass media constantly bombards the audience and keeps people farther and farther away from poetry.

Media is one of the best tools for creating an image of a state. In your opinion, does the media convey credible information about Iran? I get the impression that pressure on creators in Iran has intensified.

This question can be best answered by news media creators. I can say that I prefer to use not the word “pressure” but “restriction”. Especially since cinema itself is a restriction, since setting up the frame means to draw borders [around it].

The best examples of cinema have always been created due to limitations. Italian neorealism, for example, began during the years of the economic crisis [post-WWII] when oddly, a great creative movement began. So I think that restrictions further enrich the filmmaker’s creative thought.

| “Cinema itself is a restriction, since setting up the frame means to draw borders [around it]” |

Does Iranian TV show new Persian films?

About 50% of Persian cinema is shown on television.

What is the “national” in cinema?

If we consider cinema a mirror that we hold up to nature and then depict its reflections in films, then national characteristics cannot exist in cinema. But since the film director controls the mirror’s direction, whether you like it or not, cultural, intellectual and geographical characteristics will appear in his view. Naturally, I, as an Iranian, will see and film the same image differently than, say, an American.

The camera lens sees the reality; the director, the truth. Cinema is created when the filmmaker is able to use his inner eye and the camera’s lens correctly.

Science and recognition are limited only by the senses. We recognize that which we feel. When shooting a film I always rely on that sensor, the senses, which we have lost and which will help us feel what’s hidden behind the image.

Generally, in cinema what’s important is that which is not seen. Everyone sees how the apple falls from the tree, but Newton saw the force of gravity behind that process. I think that cinema is that hidden gravity.

Perhaps it’s due to this search for the hidden that eastern countries such as Iran and Korea today are ripe with good films?

Separating the East and the West from each other is very difficult. In my opinion, Japan, for example, can be considered more so a western country, though geographically it’s deeply eastern.

There are a lot of newspapers in Iran that cover art, particularly cinema and theatre. Does this media support help directors’ voices get heard more and increase audience numbers?

There really are many newspapers and media outlets in general, but, to tell the truth, those newspapers are more so mafia organizations (as are movie theatres) that are fed by specific sources, and if they want to get you, they’ll criticize your film so much that it’ll seriously harm you.

The media writes mainly about lucrative films or those that, to a certain extent, promote the Iranian state. And if suddenly those papers write about my films, it becomes harder to show them on the screen. My third film, The Insane Flew Away, for example, in Iran was recognized as one of the best — much was written about it and viewers were even ready to break down the doors during the festival in order to watch it. But the film wasn’t widely screened.

Why?

The permission for screening was for a very short period of time. In the film, I’ve depicted tradition and modernism in today’s reality; the hero is a guy who fights in a war and gets a concussion and sees the teacher who sent him to war is now married to his wife. And the guy has to learn how to live again…

| “Tools plus power equals technology” |

I get the impression that in Persian cinema often the starkest and most profound thoughts are conveyed through female characters. It seems, women are permitted to say that which men don’t dare say.

Yes, that’s an accurate observation. Woman and truth are always coupled.

If we don’t measure women in consumer standards and don’t turn them into an object for consumption, we will more quickly reach the truth, since as Plato said, we never learn; rather, we always recollect. And women are the bearers of truth, thanks to whom humanity will see paradise again.

Modern Armenian cinema, it seems, avoids simple human stories and tries to create more complex and intricate philosophical structures. In your opinion, why is this?

There is madness that can be called everyday foolishness because it always falls behind mind and thought. But there is also madness that comes after rational thinking. You are released from rationalism and go mad; that is, first your mind matures, then your madness. And your madness becomes wiser than your wisdom.

I want to say, when you don’t know simple things, you’re forced to take primitive steps. And profound, complete clarity matures when you reach the peak of complexity and all of sudden you feel that the next step is clarity.

Do new technologies enrich or hinder the gravitational pull of art?

When digital technologies entered the market, Jean-Luc Godard said, that’s it, cinematography is dead. But, as you can see, that didn’t happen. Of course, cinema loses its genuineness, but I’m sure that cinema will find solutions.

I want to respond to your question with an example from cinema. In Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a tribe of man-apes reclaim control over an area. One of the man-apes finds a large animal bone, which he uses as a weapon with which he hits the other man-apes. He throws this bone into the air and the scene shifts from the falling bone to an orbital satellite.

In this way, Kubrick shows that when a tool is connected to power, it becomes technology. Until then, the bone was just a useful object, but when you try to rule with it, its function is immediately changed. The computer likewise is a tool like that bone, with which they control.

The tool is in our hands and we can use it as we wish, but technology itself is using us. In my opinion, a discovery is happening now that’s just as important as the one Newton made. New, unseen depths and a new gravitational force are now being uncovered.

Today people have many tools to connect with each other, but it’s an illusory connection because man actually loses the ability to make decisions independently. Finally, the entire experience of eastern philosophy shows that man’s mission is not in being but in becoming.

Interview conducted by Nune Hakhverdyan.