The discovery and study of Mariam Shahinyan’s photographic heritage is something like an ongoing adventure novel. She is the first female photographer to work in Istanbul, for whom photography was both a business and a means of self-expression and everyday courage.

Writer and researcher Anahit Ghazaryan has been living and reliving the life of this unique photographer for a long time, trying to reconstruct (in her words, rewrite) the image of Mariam, the images she left and the unique place that Mariam carefully and meticulously built half a century ago, as a modern artist in a conservative environment.

The exhibition, “Foto Galatasaray | Living Room of Images,” which opened at the 4Plus Photo Editorial Office, is the first visible step in Anahit’s research, which may be followed by a book or film. But in any case, this is the beginning of a great archival journey.

The 27 original photos, which bear the Foto Galatasaray stamp (that is, proof that they were taken in a studio owned by Mariam), are presented as if you were flipping through a family album that someone quietly left for you, opening the living room door halfway. You can touch the photos on the tables and cabinets, touch, rotate, read the notes. To see a person and imagine time.

4Plus founder, photographer Nazik Armenakyan is sure that those photos would not be able to be hung on the wall, as the charm of the faces would be lost. And even if there are complete strangers in the photos, you can still see how the photo-taking ritual works in the pre-internet age.

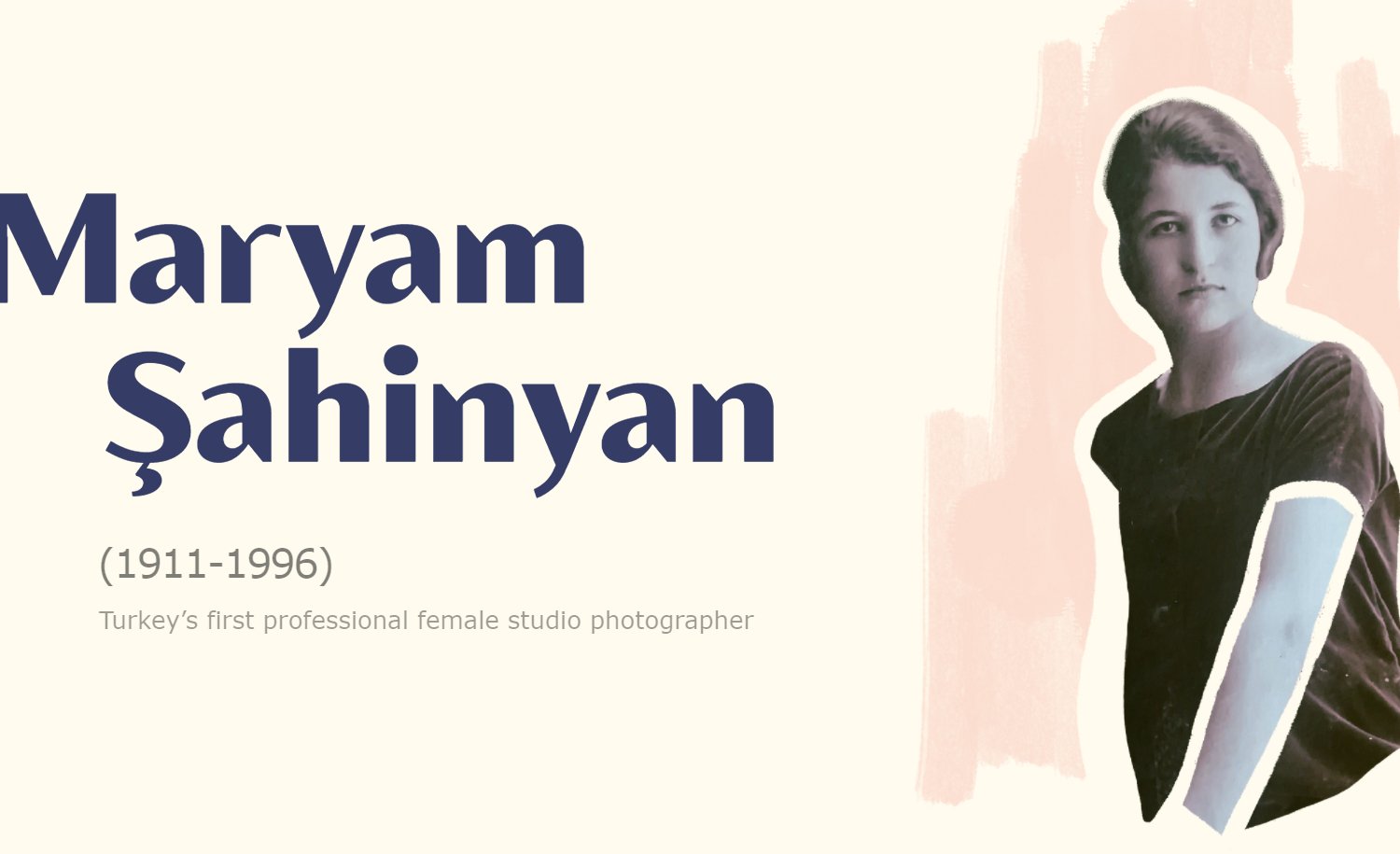

Turkey’s first female professional studio photographer Mariam Shahinyan (1911-1996) seems to have found Anahit Ghazaryan herself so that she can have a dialogue with us through our contemporary.

Anahit built the exhibition with the logic of that dialogue, with her thoughts, diaries and invitation to see what an interesting mark Mariam has left in multinational and multicultural Istanbul. How open and innovative she was in her studio and how closed and silent in her personal life. For example, among her thousands of photos, there are almost no self-portraits, the photographer usually tore her portraits, as if not wanting to be remembered.

Instead, she created portraits of more than a million people: ordinary, strange, happy and sad, free and hesitant. Mariam worked actively in 1935-1985, and then left her job completely and did not even own her rich archive.

People who knew her said that in her final years Mariam often said that she was very tired…

The issue of the archive

Mariam Shahinyan’s archive was discovered by chance. In 1994, while the photographer was still alive, the Turkish owner of her studio left the photographer’s negatives in the bushes next to a trash can in the Kadikoy district and contacted Aras Publishing director Etwart Tomasyan, noting exactly where he could find them. He probably assumed that it was important for the Armenian community.

It is unknown why Mariam Shahinyan’s legacy was transferred from the European part of Istanbul, Istiklal, to the Asian part. But the fact is that Tomasyan saved the negatives by keeping them in the basement of his house. Some were damaged and needed to be repaired.

The problem was also that the restoration and further digitalization of glass negatives required serious technical potential and professionalism, which was a difficult task in those years.

And only 25 years later, in 2011, “Aras” published a book, which included some excerpts from 200,000 images of Mariam Shahinyan.

According to Anahit Ghazaryan, now 70% of Mariam’s works are digitized, and the rest is not digitized and it is also unknown where it is.

According to her, they may be with researcher Typhoon Sertash, who also researched Hovsep Minasoglu’s archive. Minasoglu has made a huge contribution to Turkish culture. Studying at Kodak in Paris, he was the first to publish a color photograph in Istanbul. But he lived a very difficult life, he was persecuted (maybe also because he was gay), a part of his archive was burnt.

Sertash has made two exhibitions of Mariam’s works, but they were clumsy, not even Shahinyan’s name was mentioned in the title. “It’s as if the researcher has privatized the work of that rare female creator,” said Anahit.

The Shahinyan family migrated from their native Sivas because of the genocide, leaving a rich life and trying to rebuild something in Istanbul. And that one thing was the photo studio.

Mariam Shahinyan’s grandfather was a member of the parliament, the family had lands, villages, mills. Mariam’s grandfather’s house, for example, became a public post office after the genocide, that is, the largest and most luxurious mansion was chosen for an important junction building.

Collecting the private archive

Since Mariam’s negatives were not available to Anahit, she decided to collect her alternative archive.

After all, the archive is not only the photos but also the memories and stories, which are summarized in the photos. The archive also has a practical function, becoming a platform for searching for relatives or an opportunity to understand the portrait of the city and time. And Anahit decided to find those stories not through negatives, but through original photos. It turned out to be a more winding but more interesting path.

She went to the editorial offices of various Armenian-language newspapers in Istanbul, patriarchates, libraries, that is, centers uniting the Diaspora, asking those who knew Mariam to respond. And people started calling.

Moreover, not only Armenians but also Greeks and Turks, who sent their photos by mail and shared their memories. And of course, Anahit spent a lot of time with Istanbul’s antique dealers, digging up piles of photos and looking for works with the Foto Galatasaray stamp.

Interviews with Mariam’s neighbors, acquaintances, and her niece, who now lives in Paris, are also part of the archive.

Photos are family stories, and you can often find unexpected layers behind one photo. People become images, then the image acquires human features again. This is almost what Anahit does, who, in her words, eagerly wants to know everything about Mariam Shahinyan. And she can even guess Mariam’s handwriting from the composition of the shot, the mise-en-scène, or the photo frame.

In Detroit, Anahit found a man who emigrated from Turkey and took the negatives with him. Mariam personally conveyed the negatives to him, wrapping them in an announcement about her studio. This accidentally preserved statement helped Anahit understand when and where the studio was moved and on what schedule it worked.

Restoring reality is a difficult task. The reason is not only the past decades but also the caution and closure of the Istanbul Armenian community. “Being a community already means being closed,” said Anahit.

The website is also part of the research, where there are only photocopies of photos with inscriptions, references and stamps, which can be clicked to get information.

“Not posting photos was a conceptual decision. I wanted to share about the photographer without her photos. So that the visitor of the website goes beyond the image and imagines the image for themselves,” said Anahit.

On the other hand, the copyrights of the heroes of the photos are preserved in this way (the face is the property of a person).

Anahit Ghazaryan and website designer Nooneh Khoodaverdyan tried to focus the visitor’s attention on the individual nature of the photo in this age of visual noise, without overloading it with photos. They spoke about the photographer without her photos.

A matter of trust

Before the photo became widespread and accessible, it was something of a gift that provided communication and information circulation. A photo was a link sent to different parts of the world as a postcard and a personal message. Or it was kept away from everyone’s eyes, because there you and your relatives are defenseless and vulnerable.

Looking at Mariam Shahinyan’s photos, you understand that people in her studio were not afraid to be what they are. And the most important issue here is the trust in the photographer.

From the photos of Mariam, women are looking at you, who are not afraid to show their naked bodies, they are a homosexual couple, who are kissing in the frame, a transgender man is smiling in fear, sitting in an armchair. The woman is carrying her children and it seems that at that very moment in the game she is infinitely happy.

Mariam’s studio was visited by people who felt free and self-sufficient. Children, black people, men in women’s clothing, women, who seem to be from the films of the new French wave, are reflected in the mirrors as if they were part of art and a work of art.

Anahit Ghazaryan is sure that Mariam Shahinyan was a unique and marginal person. “Her archive appeared next to the trash can, she was a woman-creator, also a Christian in a Muslim environment. And the people who came to have their pictures taken by her were also marginals. Working in a conservative environment, Mariam could easily have stopped photographing those people. But she seemed to be interested in anyone who could open up to her.”

For example, women have always preferred to show their hair by opening long braids and letting them flow freely in the frame. Her studio seemed to be a little safe place, where the person appeared convinced that they were protected and wouldn’t need to hide behind conventions.

Interestingly, everyone would call Mariam Mademoiselle. It seemed that this was not emphasizing her ordinariness, but her being.

The life described by Mariam Shahinyan’s facts is very poor, incomplete (she left neither diaries nor memoirs). It can be understood that she was very punctual and meticulous at work and in a restrained and closed life.

But her photos tell a completely different, parallel life, which is really unique. Anahit Ghazaryan is convinced of that.

“It seems to me that she had two lives, one public, one internal. No one can speak about that inner life better than her photos. You open them and are amazed at how she will openly invite people to the closed area of her studio. I really admire the modern handwriting she had and sometimes even related to conceptual art.”

Anahit Ghazaryan continues to dig into various details to understand how a woman who went through hardships and lived a solitary life was able to be so free, innovative and open-minded in her profession. And to become a not-so-free society, a free documentarian.

Nune Hakhverdyan