The 1988 Movement is now a 30-year-old memory. It was one of those beautiful and unique historical moments when due to a huge internal energy tectonic plates shifted in the seemingly unshakeable rigid structure of the Soviet empire.

The people and the public square joined together, and created was a massive and harmonious body, which truly was for the masses and truly was harmonious.

As ethnographer and anthropologist Levon Abrahamyan says, it was a holiday in the classical sense and in its manifestations, both spontaneous and structured (with role reversal and carnival-like). And as with any holiday, it was replenished with details, symbols, and ritual.

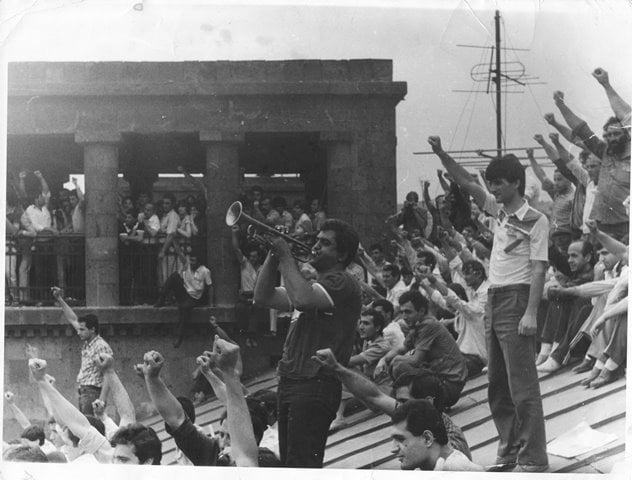

The melody of a trumpet heard during the first rallies in February 1988 and repeated for years was one such ritual detail.

The trumpet is not only a musical, but also an informing, attention-inviting, and broadly, guiding instrument. The instrument, melody, and performer appeared at a moment when an auditory symbol was needed. More precisely, there was a demand, and that demand was met.

Attending the rally, Ashot Mirzoyan removed his very old trumpet from its case and played the melody that, in his words, had long been tempered from his childhood, camp life, and … in general, it was tempered and that’s it.

Artemi Ayvazyan’s music written for the film Why Does the River Roar became a signal, a hymn, and also a call. In general, any revolution begins from the change, reinterpretation, refusal, and parallel creation of symbols.

The trumpet created an environment that was new, fresh, and unpredictable for everyone. And with that, alluring and emotional.

“It’s sad that few ask themselves where the Movement started from, and how it was that the idea to gather worked like butter and stuck everyone together,” recalls Mirzoyan, whom everyone called Shepor (Trumpet) Ashot.

A graduate of the mechanical engineering department, Ashot at the time worked as an engineer at a company called Laserayin Tekhnika (Laser Technology). And he enjoyed making music with friends. By the way, he doesn’t say “I played the trumpet” but instead says “I trumpeted.”

And like everyone in 1988, he went to rallies. In 1988, everything was arranged randomly — at the same time, nothing was random. Mirzoyan recounts:

“Kiss, who lived near the fish store and was a known Yerevan figure and who limped, said, people have gathered at Opera [square], let’s go see what they’re going to do. We went to Opera square, I had the trumpet in its case with me. A kid asked, is that a trumpet? Will you let me play it? I thought if he knows that this is a trumpet then he knows how to play it. He took it and went beep-beep a few times. People next to us shouted that they can’t hear what’s happening because of the sound. In fact, nothing was happening, since February 21, 1988 was the moment when people had gathered to go to the Central Committee to find out what assessment Moscow was going to make… But they didn’t go.

“On one hand, Soviet discipline, and, on the other hand, fear was not letting them take that risky move and march to the Central Committee building. There were so many people that they no longer fit on the sidewalks; everyone was anxiously waiting to see what would happen. And when that kid tried to sound a few notes on the trumpet and people silenced him, I said, give me the instrument. I took it and for the first time played that music of Artemi Ayvazyan’s. And that became a sign for everyone to raise their arms and make a decision. It was amazing; it’s like from the first note it became clear to them that they had to go to Baghramyan Avenue…”

And later too every time at all the rallies the trumpet was heard, preparing people, drawing attention, and becoming an impetus that here and now something important is going to happen.

Even if only that the rallies are already a reality, since only a reality can have its symbol.

The trumpet could no longer be considered just a one-time-use element; it was necessary as faith, as a chromatic chord, that would inspire confidence that everything is going in the right direction.

Mirzoyan recounts: “Someone had heard how I play, told another, and the other conveyed the news. And on February 23, 1988, the entire Opera [square] came to the gates outside Laserayin Tekhnika, located in 6th Masiv [Nor Nork 6th Microdistrict in Yerevan], and called me. And the factory manager said, go, stay as long as you have to and play.”

“If he didn’t let you, would you not go?” Laughing, he replies: “He couldn’t not let me, since the people gathered would simply destroy the factory — with its gates, walls, and so on.”

From that day forward, Ashot Mirzoyan gave the start of all the rallies with his trumpet. If the trumpet called, then the rally was already ripe and soon the speeches would be heard. And like this until 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, and independent Armenia elected its first president.

Assuming the same role with the same instrument for years never bothered Mirzoyan. “Until the collapse of the Soviet Union, the trumpet was topical.”

He disappeared from the Square only for one month, when he went to Tashkent (Uzbekistan) to make money. “Money had depreciated so much that we were forced to earn money,” he said, adding, “Of course there was a substitute [trumpeter].”

Artemi Ayvazyan’s melody for Mirzoyan was connected initially with his childhood memories. “Few people had a TV, and those who did always expected that a lot of people would be gathering at their house. And when my parents and the neighbors would watch movies on television, they would send the kids to bed. From under the blanket I would try to see and hear what they were watching. And that music had made an impression on my memory.”

The trumpet is not only a symbol of collective energy, victory, and the new, but also an intervention of tolerance and reconciliation. There were instances when due to the trumpet’s notes conflicts were settled and emerging clashes were mitigated. As soon as the music was heard, the crowd got an opportunity to suppress minor discomfort and ambitious thoughts.

“I felt the power of reconciliation technique for the first time at Zvartnots Airport, where in June 1988, the Soviet forces had created a barricade and prohibited entry. The soldiers with their shields next to each other had created a human wall, and in front were several hundred people, mainly women in a fighting mood who had filled their handbags with rocks, and with whatever strength they had, they, swinging, were trying to hit the Russian soldiers standing behind the shields. They had built a real weapon. It was an explosive situation, as the soldiers were waiting for an order to crush the people. And I managed to trumpet… I’m sure that if I was a few minutes late, a bloody massacre would’ve broken out… Really, when the trumpet sounded, it’s like a light went on, everyone stopped at once.”

In 1988, the trumpet was identified only with good things. Including also order. The huge mass of people were guided by the trumpet. The trumpet was a compass and a watch.

And now that compass and watch trumpet is a museum artifact, which has found its place in the History Museum of Armenia.

A few years ago, Ashot donated the trumpet (which he had taken with him to the US and brought back) to the museum.

“It seems now no one is interested in the history, the what, how it began. I get the impression that now all the media outlets, once they see that someone with a broom standing in the corner, they go and ask, what do you think about this, about that. And it doesn’t interest the journalists what answer that person will give; the journalists already know what they’re going to write and what report they are going to produce. They simply pretend that they want to know the truth,” he says.

Now in 2018, the Movement is viewed from a different angle. Rather, standing still, in the middle of a break.

Nune Hakhverdyan