It was 1996, and Armenia was in disarray. French journalist Anne Dastakian had just returned from Yerevan. She had covered the presidential election for French newspaper Libération.

In Prague with Dastakian and Czech journalist Dana Mazalova, we discussed the elections in Armenia.

Anne had gone to Armenia as a journalist for the first time, while Dana had been a few times and loved citing one of the newspapers: “Levon Ter-Petrossian didn’t respond to journalists’ questions but came up to kiss the Czech journalist.”

Initially, the conversation took place in Russian, which we all understood. But Anne and Dana began to argue and switched to Czech. The more heated the argument became, the less they noticed me. My colleagues from abroad were going back and forth on my country’s troubles, and I barely understood a word. Finally, they became cross with each other. Because of my country. No matter how much I asked, what was it about Armenia that made you argue so, neither gave me a proper response.

The year is 2016. Exactly 20 years after this argument, I am to write about Dastakian. From Yerevan to Paris, this is my first written question. Finally I want to know what my French and Czech friends were arguing about Armenia. In vain. I receive this response from Anne: I honestly don’t remember.

Anne Dastakian, Prague, 1997

Anne Dastakian is now a journalist of the international section of the influential French weekly Marianne. “We’re three people [covering] the entire world. My area is primarily post-Soviet countries, Central Europe, and the Balkans.”

Anne has been with Marianne since its inception in 1997. Marianne has a print run of 300,000. According to Wikipedia, in 2007, when the weekly began a campaign against presidential candidate Nicolas Sarkozy by publishing “The Real Sarkozy,” the publication reached record sales for publications in France — about 580,000 copies.

I ask Anne: did you participate in that counter-campaign and generally speaking, is it correct for a newspaper to campaign for or against anyone?

“Since I don’t cover France’s domestic affairs, I myself didn’t write about election topics. As for my colleagues at Marianne, no one ran a counter-campaign; critical facts were published (probably Sarkozy believes it was a counter-campaign). Now too when we have such facts against the current government or president, we publish them.”

After the deadly attacks on the staff of Charlie Hebdo, has Anne reviewed any of her journalistic approaches or principles? No, she says.

– Are you familiar with the internal work practices of news media in Armenia? Would you like to work for the local media?

– I’m not familiar, but judging from what the local Armenian journalists I know describe, I think it would be very difficult to remain an independent journalist in Armenia. On the other hand, I wasn’t born in Armenia, I don’t live there, I don’t know the language…

Madame Liliane, Anne’s mother, is French, from Monte Carlo. Her father, Karen Dastakian, was born in Tbilisi, in 1920; his parents had just moved from Baku. Anne’s paternal grandfather, Abraham Dastakian of Shushi, according to some sources, was one of the founding members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun). He was the health minister of the First Republic of Armenia.

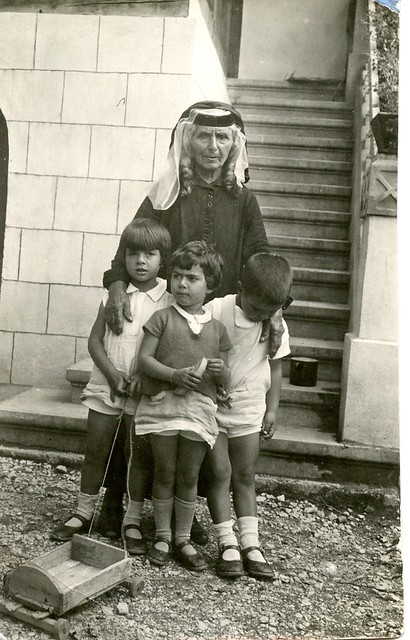

Anne Dastakian’s grandmother Ashkhen with her children (Karen, Nina, and Anne)

Photograph taken around 1926, Bucharest

Anne was born in Paris, where her father had long settled. She studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and the Czech language at the National Institute for Oriental Languages and Civilizations in Paris. “Why Czech? My friend, who became my husband, received a scholarship to study in Prague. When I visited him, I fell in love with the city and decided to learn Czech. In 1980, I too received a scholarship to study in Prague.”

In 1984, Anne left for Moscow with her French diplomat husband. “We managed to see the year of Chernenko’s rule, Gorbachev’s coming, perestroika, and the rest… Within the USSR, our first trip was to Armenia. On Saturday and Sunday, we went to Yerevan, Garni, and Geghard.”

In 1986, Anne divorced and returned to France. Her son, Antoin, whose father is Russian rock musician Vasily Shumov, was born in 1987. Till today, Anne greets Antoin in the Russian diminutive form, Antosha.

They returned to Moscow. Initially, she was an editorial assistant with the American broadcaster NTV, then she began working at the Moscow office of Libération.“When the earthquake happened in Armenia, I was alone: the correspondent was on vacation; I was translating what I found and what I could from the Russian press.”

Returning to France in 1989, Anne underwent training at Le Monde and began to write articles. She witnessed the Velvet Revolution in the Czech Republic: she was there simply to celebrate her birthday jubilee. “And when Václav Havel became president, I decided to become established as a journalist in the Czech Republic. There I worked for Reuters, Le Monde, Agence France Presse, and Libération… in 1995, I returned to France without a job.”

Anne’s grandmother Ashkhen’s mother Zaruhi, who spoke only in the Karabakh dialect.

With her are her grandchildren Nina, Lily, and Karen.

Photo taken at the end of the 1920s, Bucharest

In 1996, after her first visit to Armenia as a journalist, Anne has frequently come to Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh for work. She has covered various issues from different sectors. The last time she was in Yerevan was autumn 2015. Upon the invitation of entrepreneur Ruben Vardanian, she went to Dilijan, Tatev, and Jermuk with other French journalists. She published an article in Marianne on the Syrian-Armenian refugees settled in Armenia, which was picked up by the French-Armenian press.

Last year, she published a special series in Marianne, 100 pages on French-Armenians, and from April 20–23, she was in Diyarbakir, from where she submitted a reportage on the centenary of the Armenian Genocide. In 2006, proclaimed the Year of Armenia in France, Anne published the book 100 Réponses sur le génocide des Arméniens (“100 Answers on the Armenian Genocide”) with French historian Claire Mouradian.

“In 2006, we had come to Armenia to visit Lake Sevan with tourism [industry] experts. Arriving in Yerevan, we discovered that in France, MPs had voted in favor of the bill criminalizing Armenian Genocide denial. We were quite surprised because nearly everyone in France was against that bill.”

– Anne, you’re a French journalist, but you very frequently cover Armenian topics. Is this something you need to do because you have Armenian roots, or you believe that they’re interesting to others as well?

– As a French journalist with Armenian roots, I’m interested in what’s happening in Armenia. And when I have specific information, I dig deeper. I write sometimes short news pieces and sometimes lengthy articles on Armenia for Marianne.

– Have you ever been subjective in Armenian matters? Especially when covering Armenia’s problems with Turkey or Azerbaijan.

Anne Dastakian in Jerusalem, with an Armenian boy

– I think, no. But, for example, I was quite affected when I was writing about the destruction of Jugha‘s khachkars. It was hard to find a tone that was not emotional. I had to seek the help of my colleague. But in general, when the issue has to do with Turkey or Azerbaijan, it’s always easier to stand beside the victim than the opposite. Azerbaijan is even grotesque — it provides many occasions to laugh at its regime. By the way, though I’m a French citizen, I can’t travel to Azerbaijan because of my Armenian surname.

Many years ago before one of her regular visits to Armenia, Anne asked me how to say “thank you for the interview” in Armenian. Why do you need to know? She said that after interviews in Armenia and Karabakh, she wanted to thank interviewees in Armenian. I decided to play a little game. I said, you have to say, “Let me kiss you”. She began to loudly repeat “Let me kiss you” in order to learn it. But my Armenian colleagues heard her and said, Anne, what are you saying? She said, nothing, I’m memorizing how to say thank you for the interview in Armenian. Who told you that…? I was caught much earlier than I planned to confess.

– So you never learned Armenian.

– When I was young, I could’ve, but it didn’t work out. In France, they teach you only Western Armenian. When I was in Prague, I learned a bit of Eastern Armenian. With any Armenian [person], we can find a common language in which to communicate. Knowing Russian saves me. But I’ll learn Armenian too.

Interview by Ruzanna Khachatrian