When Polish State Television (TVP) journalist Marcin Mamo left for Yerevan from his correspondent point of Tbilisi at the end of last year, to cover the parliamentary election, the Armenian border guards kept him at the Armenian-Turkish border for about two hours.

But as a result, hew as allowed to enter the country.

“The delay at the border is probably a reaction to my name being blacklisted in Russia. I appeared on the list after interviewing Doka Umarov in the mountains of Chechnya. That list is somehow spreading to Armenia as well, and I learned of it in 2008 when I was trying to enter Georgia through Yerevan during the Russian-Georgian war. At that time I was sent back from Zvartnots airport,” said the 50-year-old journalist.

But this time, about an hour after the TVP correspondent and his cameraman Tomasz Glovatski, the Armenian border patrol announced that everything would be fine, but we should wait for a little. And in fact, after a while they allowed them to enter the country…

Marcin has a very rich and interesting biography that has been predetermined even in his youth in the 80s. At that time, Poland was fighting against the Communist rule of the country. Margarine Mamo, a young Krakowian, became a member of an underground group, actively participated in the movement, wrote for self-published periodicals, and went out to demonstrations. She had been arrested and beaten…

The end is well-known. The Communist power in Poland failed.

And when it came time to choose a job, Marcin, a graduate from the Faculty of History at Krakow University, decided to become a journalist. He already had the experience of self-publication, besides, his father as a well-known journalist.

But the way of “quiet” journalism did not tempt the young Polish state television correspondent. It is important to note that the struggle against the Communist system was a struggle for many Poles against the Soviet Union or even against Russia.

Taking into account the difficult history of the two countries, there is still an anti-Russian sentiment in Poland, and many things are viewed through that prism.

Marcin’s attention to the war in Chechnya was not accidental. “It was very interesting for me to see people with my own eyes, who were not afraid and who struggled against the great empire,” said the Polish journalist.

Particularly, the topic of his diploma was about the Russian-Caucasian people who served in the Polish army after the communist rule of Russia came to power.

The Polish journalist visited Chechnya more than ten times, preparing films for different western media. He became acquainted with influential field commanders, enjoyed their respect, and became for some, a person they would call “brother.” By the way, this brotherhood helped Marcin a few years ago when he was captured in Syria…

In the 90s, when his film about Chechnya was shown on Channel 4 in England, where he had his interview with Doka Umarov, it was forbidden for Mamo to visit Russia. But after that, he came to Chechnya where by means of the Georgian Pankisi Gorge, where he got acquainted with Gelaev and his men.

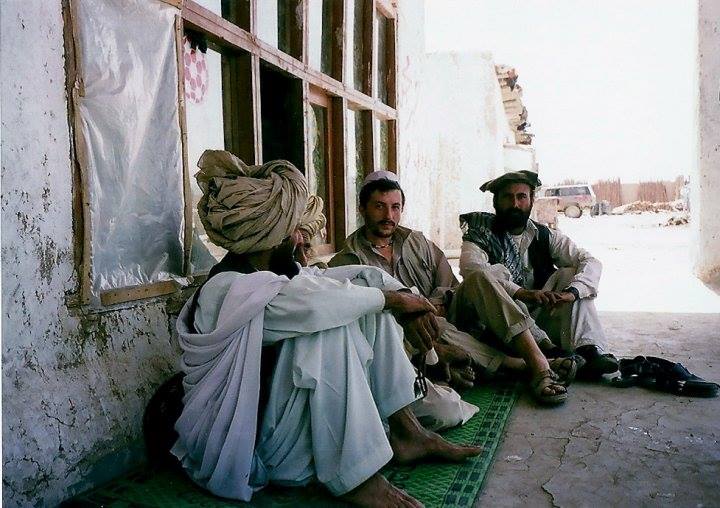

The path of the stringer was quite interesting. In addition to Chechnya, Marcin has been in many (primarily Muslim) countries, where there has been, or remains to be a complex internal situation – Syria, Egypt during the revolution, Afghanistan, Somalia and so on.

During the war in Syria, he lived through perhaps the most difficult period in his life. They took him hostage and demanded ransom from Poland.

“I think I was “sold” to one of my Chechen friends. It’s impossible to find out what actually happened because that person is no longer alive. Nevertheless, such developments of events are evidence of the circumstances. But the Chechens also saved me from danger,” said Marcin.

When Marcin went on a regular business trip, he had left his wife with a list of contacts to whom she could appeal for help in the case of danger. That too helped. When the Chechen “brothers” learned that the Polish journalist and his operator were held as hostages, they made it so that they were set free and healthy and without paying any ransom.

“Everything happened in a very interesting way. My Chechen friends were able to carry a court case based on Sharia law and it was decided that ‘Although we, the others, are not loyal, we have been invited here according to all the “rules,” that is why we should not be taken hostage and a ransom is not permissible,” said Marcin.

The Polish stringer says that he had no fear during his time as a hostage. “I just know those people. And if you know them, you know what to expect from them… I only worried that they would sell us to the fighters of the Islamic State. In that case, everything would have become worse.”

By the way, Marcin assures that the knowledge of Russian is very useful for him not only in the Caucasus but also in other parts of the region. He communicated in Russian both in Syria, where many Caucasians were born and in Afghanistan where there are still people who remember the Russian language.

Naturally, language helps in the South Caucasus. Last year, he joined the TVP’s Tbilisi correspondent. Apart from covering the events of the three South Caucasus countries, he also followed the news of the whole South Ossetian region.

According to Marcin, Armenia didn’t leave much of an impression after crossing the border. On the contrary, he noticed immediate poverty and depreciation of infrastructure compared to Georgia.

Besides, he was pleasantly surprised by the technological advancement of our election. “During the presidential election in Georgia, they put a special mark on the fingerprint. I’ve seen such a thing in Afghanistan. Things in Armenia are on another level, the system is electronic.”

Marcin was a little confused by the lack of anti-Russian sentiments in Armenia. It seemed to him that after the change of power, Armenia and its people should strive towards the West.

According to the Polish journalist, Russia, unlike the West, cannot provide progressive development for the country. But getting acquainted with the geopolitical realities and the people’s disposition, he understood that everything was not so easy.

“For us, Armenia is Russia’s main friend in the Caucasus, and when we learned that everything is changing here, it gave us hope. I hope Pashinyan will change the situation. Of course, I do not know how. Despite my awareness of the region’s problems, I better understand what geopolitical situation Armenia is in,” said Mamo.

Nevertheless, Marcin Mamo hopes and even dreams that Armenia and Azerbaijan will be able to reach an agreement. He has a special attitude toward both countries.

Marcin’s mother originally came from the tribe of Eminovic’s, the founder of which was an Armenian merchant in Poland dating back to the 17th century. On the other hand, among his friends, there is also an Azerbaijani, former Soviet officer, who hid in service in Poland and defended the country during World War II.

Marcin is going to come to Armenia again this year to get better acquainted with the country and to make new reports.

Karen Arzumanyan