On November 9, a large part of society made a sharp transition from the mood of “we will win” to the reality of “we lost.” This transition was more painful because there was a certain information vacuum in the country. The media provided almost nothing to the public except official information.

During the Second Artsakh War, the media in Armenia was subject to triple censorship. The work of journalists was limited by the state on the one hand and the audience on the other. Finally, the self-censorship of journalists sometimes was no less restrictive than those of the state.

Fact-checking and investigative journalists had a certain advantage: they used open-source data to convey a little more information. However, the “three-layer” restrictions also complicated the fact-checking process.

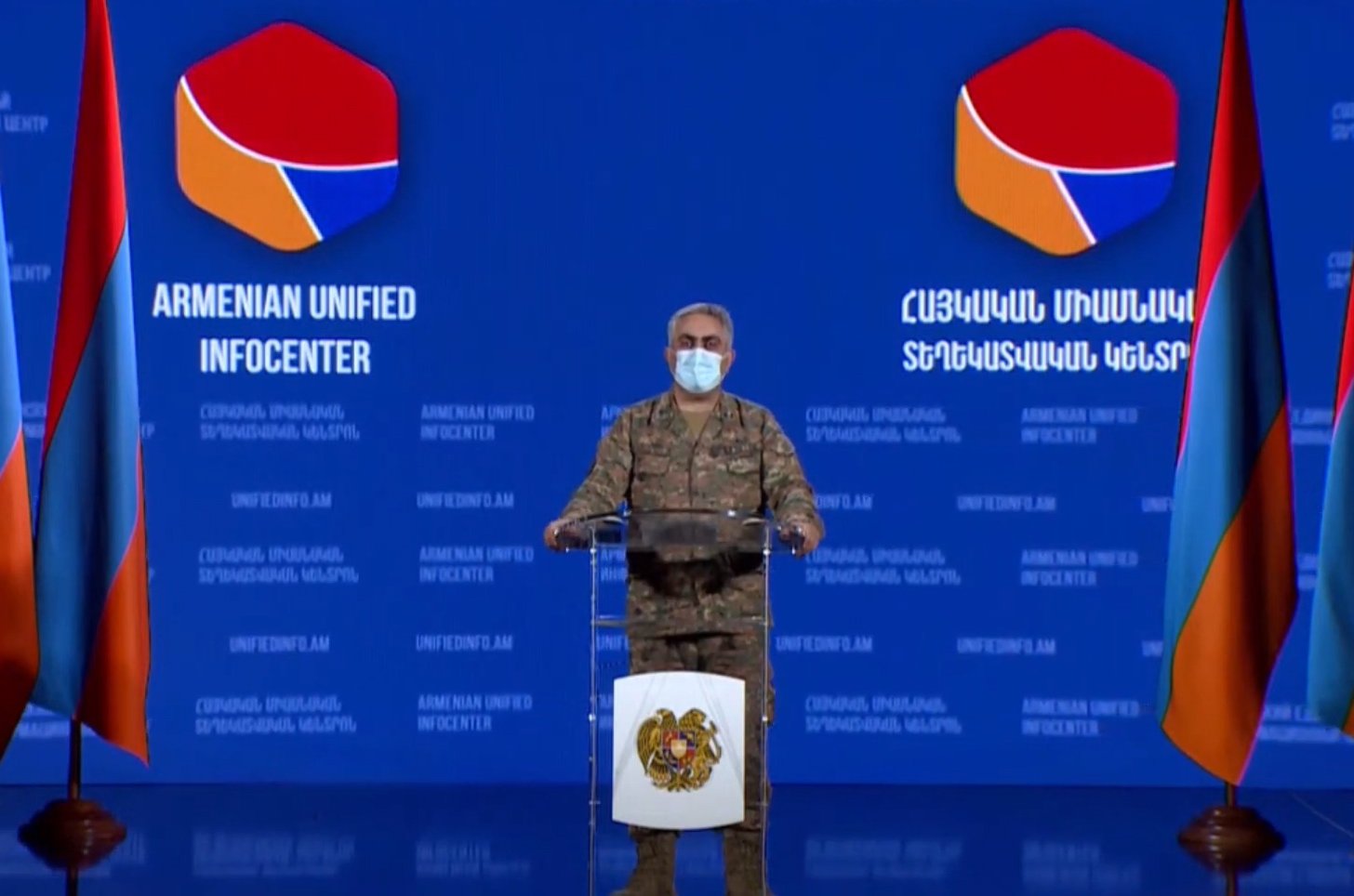

State information – state propaganda

From the first day of the war, martial law was declared in Armenia, which meant that the state banned both the media and non-media outlets from reporting unofficial information. Violation of this ban could threaten the media with a fine of up to one million AMD.

The ban did not remain on paper: at the end of October, 9 media outlets were fined 700,000 AMD. One of them received an additional fine of 1.5 million AMD for not removing the publication.

The state restrictions also applied to foreign media. First, there was a special procedure for accreditation of journalists, and Armenia could not allow the work of any old news outlet in the country. Second, the journalist’s credentials could be revoked. Thus, the credentials of the journalist of the Russian “Novaya Gazeta” Ilya Azar were revoked after his scandalous report about the difficult situation in Artsakh. Joshua Kuchera, the editor of the English-language Eurasianet website, also failed to obtain a credential to work in Artsakh. Both journalists have long been banned from working in its territory by Azerbaijan.

The State also “closed” state databases due to Armenian-Azerbaijani hacker attacks: until today the websites of the state register of legal entities, the register of voters, etc. are not available. This also significantly complicates the fact-checking and investigative journalism work on topics not directly related to the war.

Of course, in any country during a war official news becomes propaganda. It is possible that both the journalists and the audience will realize this. For fact-finding journalists, this meant that if in the past it was difficult to build an article based only on the denials of state bodies, in the days of the war it became impossible.

Fip.am editor-in-chief Ani Grigoryan said, “The most difficult thing was to verify the official information. On the one hand, the information provided was quite limited, on the other hand, it was almost impossible to verify at that time. I worked in Artsakh during the war. In many cases, I reported that what was happening on the spot and the official information would contradict it, but the restrictions of the martial law, to some extent the censorship, made me keep silent.”

Alternative maps

The maps displayed by the Armenian Ministry of Defense at daily briefings in the evening were not the only visualization of the situation on the battlefield. Foreign experts and journalists mapped the situation based not only on Armenian and Azerbaijani official statements but also on localized images. In other words, the map of the progress of the Azerbaijani side was made based on the photos or videos, whose shooting locations were geolocated. The videos published by the Ministry of Defense of Azerbaijan were compared to a satellite photo; if it was confirmed that they were actually shot in the announced village or town, that settlement was included in the occupied territories. The same referred to the images published by the Armenian side.

Confirms Azeribaijan’s seizure of Jabrayil https://t.co/OYA7jPmYaM pic.twitter.com/xaMzHicF35

— Ryan O’Farrell (@ryanmofarrell) October 7, 2020

Maps based on positioned images were not widely used in the Armenian media (instead, they were published by the international media). They did not make many attempts to create alternative maps.

Open sources

During the war, fact-finding and investigative journalists were more likely to use both satellite imagery and other open-source images. The advantage of open sources is also that there is no need to make a request and wait for information from the state.

For example, when it was announced that the military airport in the Azerbaijani city of Ganja “disappeared,” pictures of another airport in the city of Lankaran began to spread on the Internet as evidence. It was not difficult to deny this information. The name of the city of Lankaran was even written on the building in the photo. At the end of November, satellite images refuted the official claim that Ganja Airport had been destroyed.

Another example is the rumors about the involvement of mercenaries in the war, which the Azerbaijani authorities called “fake news.” This information was confirmed by international and Armenian journalists thanks to the photos and videos published by the mercenaries on social networks.

Finally, journalists collected numerous fake pages opened in the names of Armenian media outlets and officials, as well as keeping up with the Armenian-Azerbaijani Twitter battles.

Throughout the Second Artsakh War, open sources provided a variety of materials worthy of analysis. Analyzing images and other data, journalists were able to find out the truth, often without contacting government agencies.

“Open sources played a significant role in uncovering the vandalism committed by Azerbaijan in the territories occupied during the war. For example, studying the videos disseminated by the Azerbaijani soldiers with various tools, we found out that after the capture of Shushi, the famous Green Hour Church was partially destroyed,” added Ani Grigoryan, Editor-in-Chief of Fip.am.

Restrictions from martial law and the state of war, however, made it extremely difficult for journalists to receive information and publish it, to verify information, investigate, and witness the situation in Artsakh.

Karine Ghazaryan