In the middle of the last century, an attempt was made worldwide, including Armenia, to spread Esperanto as a language of international communication. Esperanto, an artificial language, was created by Ludwik Zamenhof in the 1800s.

In 1920, the USSR attempted to make Esperanto the language of “the proletariat and revolution.” Newspapers and autobiographies were published.

Literature was translated into that artificially constructed language. The work of spreading Esperanto in Armenia was taken on by academician and linguist, Gurgen Sevak.

He translated works of Isahakyan, Charents, Tumanyan and Shant into Esperanto.

Mass media and the press were also used in order to spread and spark an interest towards that language in Armenia.

In 1910-1914 The Caucasian Esperanto (“Kaukazka Esperantisto”), a bi-monthly literary magazine, was published in Tbilisi, in Armenian, Russian, and Georgian. The editor was H. Astvatsatryan.

The works of Armenian, Georgian, Russian and authors from other nations were translated into Esperanto. Works by Pushkin, Chekhov, Kupri, Hugo, Mopassan etc. Armenian authors Smbat Shahaziz, Alexander Tsaturyan, Avetik Isahakyan etc.. The magazine also spread to Moscow, Warsaw, Tabriz and Paris.

No copies of this magazine were kept in neither the National Library, nor the archives of Charents Museum of Literature and Art.

Though after 1914, no Armenian newspapers published in Esperanto, translations were still made.

According to the April 4, 1935 publication of the newspaper Avant-Garde, G. Sevak translated Charents’ poems, which were going to be published in the same year, however had never been published, into Esperanto.

After the Second World War, Esperato had an opportunity to become the official language of the League of Nations, but the French side vetoed the decision.

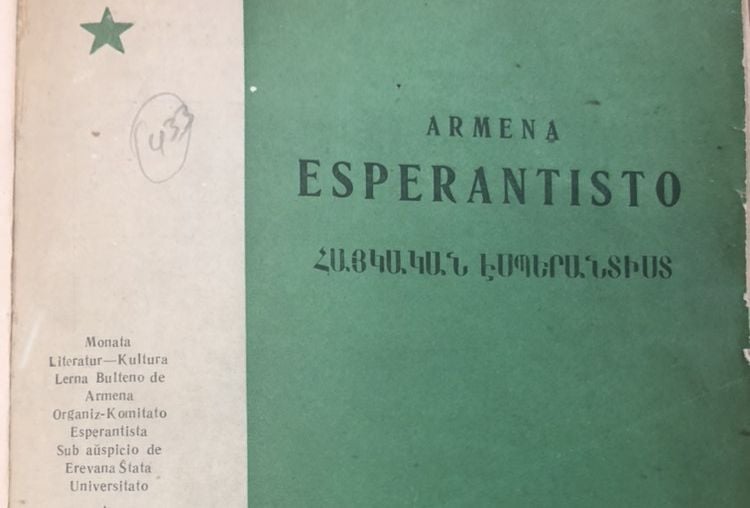

In 1958, the 16 page magazine Armenian Esperanto (“Armena esperantisto”) began publishing. 1000 copies were printed.

We read in the first issue what problem the Armenian Esperanto wanted to solve.

“We are delighted to publish the first issue of the Armenian Esperanto bulletin. Our task is, first of all, to give a choice style of reading materials for new esperantists, and to serve those who desire to learn the international language, but who cannot find textbooks and dictionaries.”

There was also a reference in the magazine to the 1910-14 Caucasian Esperanto publication.

“Yes, the Caucasian Esperanto honorably took the torch of nations’ brotherhood and internationalism, presenting the world’s Esperantists to the Caucasian peoples’ literature beauties by translating them.”

The Armenian Esperanto had kept all the rules of the magazine, by trying to provide pleasant and long-lasting readings with interesting materials. The article about the astrophysicist Viktor Hambardzumyan, Hovhannes Tumanyan’s A Drop Of Honey, in Esperanto, other translations, comics, a song about Yerevan.

Also, a course for those who want to learn Esperanto.

It was clear from this lesson, that Esperanto has 28 letters. “Most of these letters, besides 6 letters which have special markings, are familiar to everyone from school.”

Esperanto is considered an easy-to-learn language, since it has an important advantage, it is written as you hear it. The emphasis is placed on the vowel found in the second to last syllable of the word. By the way, in Esperanto there are Armenian words, khachkar, lavash-lavaso…

The magazine, however, could not have a long life, there weren’t enough people interested in Esperanto for them to have a magazine.

Even with the efforts of international organizations, it is impossible to forcefully impose an artificial language on people as a means of communication, no matter how easy it is to learn.

Curses and blessings… Without an emotional component, no language can be viable. Witness, Esperanto.

Lilit Avagyan