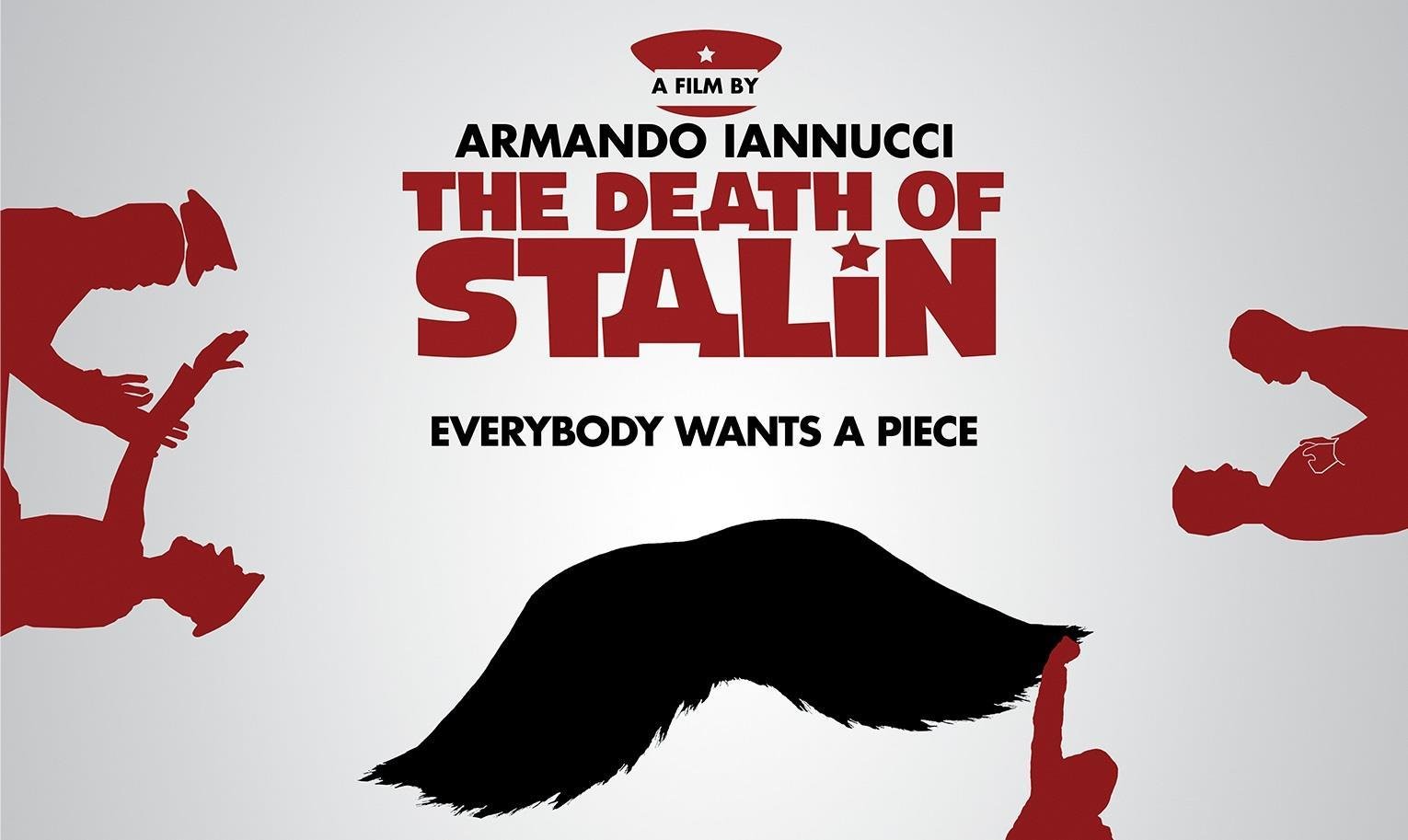

It was obvious, that when the British comedy The Death of Stalin was banned in Russia, it wasn’t for aesthetic reasons. No laws were violated either, as there was a legitimate right to screen the film.

This is a case of an ideological barrier, as only the genre of the film (grotesque comedy) and the myth of a new Russian state pillar (based on Stalin’s image) did not allow Russian state institutions to tolerate the idea that the death of Stalin could be open to interpretation, and a happy one at that.

It is against the essence of propaganda.

Propaganda prefers to deal with messages made with a serious facial expression and in no way tolerates sarcastic tones. The preacher ridicules someone else, the chosen target, but he responds to the laughter around him in a strange way. He forbids laughter (however ridiculous it seems).

In Russia, the film was called “morbid,” “evil and unnecessarily alleged as comedy,” “another attempt of psychological warfare against the country.”

A group of artists sent a letter to the Ministry of Culture, with the view that the film “instills hatred and animosity, humiliates the dignity of the Russian (Soviet) man.”

Finally, it is “extremism,’ because “the film tarnishes the honor of our citizens who defeated fascism.” As a result, the Russian Ministry of Culture deprived the film The Death of Stalin from its screening license and fined several cinemas which had already screened the film.

In recent years, Russia has been propagating the concept of the “mighty homeland.” Furthermore, Russian propagandists imply simultaneously both the Soviet Union and the existing Russian Federation. The propaganda deliberately tries to erase the boundaries between these two realities, as they place an emphasis on taking pride in the connection.

Stalin is a key figure and source of pride, who ensures the continuity of the myth of a strong leader, of the “iron fist.”

During Putin’s presidency alone, more museums and memorial plaques have been dedicated to Stalin, than in the last 20 years of the USSR.

Stalin is the most prominent name in today’s Russia. According to the results of a survey in 2017, 38% of Russians refer to him as the most well-known person of all time.

They are so accustomed to seeing Stalin as a figure of greatness (he made some mistakes, but he is still a man of greatness) in soap operas, programs and other media content, that the audience has formed an idea that a “great” man can be glorified (of course, a little bit, slightly prosecuted), but you can never laugh at him.

If you are laughing at Stalin, then you are automatically laughing at today’s leaders, because they are both great, large and worthy of glory.

Laughter has always played a destructive role. It has helped to eliminate unnecessary pieces and to build a new situation, person, era, and ideology.

Modern Russia doesn’t need anything new, it is constantly circulating the might and the glory of the former empire of the USSR, creating a mixture of nostalgia and patriotism and transferring it to the present.

It’s natural that this diligently created mixture plays the role of a straitjacket. They convince the public, that those stupid people who question the past (God forbid) and make fun of it, are enemies.

It turns out, that the enemies have created this film, and the state is now saving the audience from that enemy.

The Death of Stalin was filmed based on a French graphic novel, and is a very funny film. The laughter is based on the fact, that there is no authority for sanctification and violence, for the salvation of the homeland or for any other noble ideas.

The point is, when power is absolute, it always ends badly. For example, if you want to have a monopoly on violence, you will end with a funny death in a funny grunt. Like Stalin, and at the end of the film also Beria, followed by all the rest.

As a rule myths are rarely logical and are addressed to the audience’s emotions.

In the film The Death of Stalin, for example, there isn’t even a mention of fascism, as claimed by the film prohibitors and Russian clergymen, who say the film is “filled with Nazi ideology,” “a fabrication of the Russian public,” and the creators have become “those who spit on Russian history.”

“We must present our history, and not assign that task to others,” said a representative of the church.

Russia needs Stalin, who according to the myth, placed the responsibility of the future of the empire on his shoulders. If the film is trying to create a laughable situation and a story which overcomes fear with laughter, then it “weakens the people.”

These absolutely illogical characterizations make it evident, that the Russian propaganda machine has taken a course which can no longer be directed by sober judgement or take a break.

Scottish filmmaker, Armando Iannucci has created an absurd comedy where everyone is a victim because both the killers and the victims are living every hour waiting for their expected death. They are ready for murder, and even know, that with the same stroke of luck they can become either the killer or be killed.

In such a situation, you can only face death with laughter. That is to say, let the historical events and figures keep their necessary distance, be packaged with another cultural piece and be freed from violence by being dismantled.

This very transparent message is served to the audience on a platter, with interesting actors (for example the brilliant Steve Buscemi, playing the role of Khrushchev) and beautiful English. It suggests looking at history in a completely different, humorous way. It is precisely that invitation which is dangerous to the Russian propaganda machine, whose aim is to have the monopoly as the sole interpreter of history.

Leaders who came into power by force do not need to interpreters, they only need those who will submit themselves to the general line. Dictators from all time periods and countries want to speak about the salvation of the motherland and the necessary sacrifices with a serious facial expression (it doesn’t matter if it’s fake, the important thing is that it’s serious).

All tyrants subcounsciously know, that loud and full laughter shakes their standing.

Several post-Soviet states included in the EaEU also didn’t want to be rattled. The Death of Stalin did not reach the big screens in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan.

In Armenia, the film was screened in two cinemas, but only for four days, as the film exhibiting company was Russian and is subject to RF laws.

In Russia, Stalin is not yet dead, as Armenians were made aware four days later.

Nune Hakhverdyan