This article is dedicated to Soviet Armenia’s years of stagnation, where there was no tragedy and there was an unexpected happy childhood and many young parents.

The Armenian press entered my childhood in 1977–78, when I was a first- and later second-grade student; its entrance was very lively, noisy, happy, witty, and unexpected. Central Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia organ newspaper Sovetakan Hayastan (Soviet Armenia) became a very prominent part of my childhood for one reason: I had nowhere to stay after class, I didn’t like the after-school program, and my PhD student father as a second job was a proofreader at Sovetakan Hayastan.

The Myasnikyan district committee building was on Isahakyan St., which housed the editorial office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia’s, Armenian SSR Supreme Council’s, and Council of Ministers’ organ newspaper Sovetakan Hayastan, Armenpress, and a publishing house. The Central Committee had inadvertently made a farsighted move, locating the Sovetakan Hayastan editorial office on the first floor, because it was only due to this position that I had shelter from 12:30 pm to 6 pm. I loved the two windows left of the Isahakyan St. entrance more than my school, more than any other building in Yerevan.

The entrance was guarded by police officers and my father couldn’t get me inside. But a solution was found: he would lift me up from beneath the windows, and any one of his proofreader friends inside would pick me and my bag up. Then my father would enter from the main entrance and the happiest communication between me and the Armenian press would begin.

The highly young by today’s standards proofreaders working here were all PhD students and researchers. They were young and educated people; they had a never-failing wit, with which, it seems to me, they overcame the difficulties of life, the punishment of reading Sovetakan Hayastan until dawn, the worry of supporting a family without additional income. They were the only people reading Sovetakan Hayastan in the Armenian SSR, who did that dull work with humor worthy to become literature. They had found all the ways of making a dull life happy, one of which were highly valuable imitations, when they obligingly read and edited Armenian SSR leaders’ reports and speeches. Several times I heard how those young people edited with a professional imitation those boring speeches, and the room full of smoke, with thick, gray columns, and the newspapers with the their hot-off-the-press smell would become a source of loud, course laughter and everything was happy.

Proofreading in those years was a far cry from today’s super clean and effortless action to correct copy with one or two clicks.

Lodged in my memory are the Sovetakan Hayastan papers containing text from top to bottom that were printed for the proofreaders. Any one of the employees sitting near the four tables would read the text; the other would correct it. The corrections were brought to the margin with a long line. The news article set by the employee working on the Linotype machine was this way compared with the original, the employee’s arrangement was corrected and again sent to be typeset. And this unpleasant and not easy action was repeated as many time as errors were caught.

I remember when after reading and sending the paper to correction four times, they, tired and constantly smoking, would read with great hopes that it was the last time and suddenly a typo was found. They would utter such exclamations that only men watching football say when the ball ends up in their own goal post. My mother would come to the newspaper editorial office to get me at 6 pm, while my father often stayed until dawn, to correct the unmatched daily paper.

The newspaper had unbearable, uninteresting sections: a [Communist] party section, a Marxist section, industry and agriculture sections. And reading about the “resounding” successes of these sectors were young men and women who read the world’s valuable literature and listened to music.

Censors. They were the arch rivals of proofreaders. It wasn’t possible without them. If the censor didn’t sign the page, the paper wouldn’t be published. The censor would underline the corrected line or word in red ink. In the editorial office, there was a censor by the last name of Muradov; the employees would tell very happy stories involving him. Muradov was Kurdish by ethnicity and knew neither Armenian nor Russian well. One day, in an issue of the paper, it was written that some factory produced this many linear meters of sheet metal. Muradov had underlined it in red and told my father, “Remove this line — what do you mean ‘sheet metal’?” My father had explained, but it was only after calling the editor, Kroyan, that Muradov had allowed the use of the word sheet metal.

Over two years, I never saw editor Kroyan because when he would go down the corridor to the proofreaders’ room, the employees would hide me under the tables. I have heard only his voice.

My father and his friends would do extraordinary imitations also of Kroyan’s voice and would often play cruel jokes on each other. After the paper’s last check, someone would call and, in Kroyan’s voice, strictly order them to read the paper again. Then it became known that the caller was one of their friends. Once, Kroyan himself called and said there are typos and the paper must be read again. The proofreader who answered the call got mad, being sure that it was his friend and sending the editor to hell with very strong words. Kroyan asked for an explanation and discovered that his staff have been imitating him. The next day nothing particular happens. He enters the room and says, “So, boys, you’re teasing me, are you?”

Also printed here was the Moscow paper Pravda for Armenia. The paper’s blueprints would reach Armenia on an overnight flight and a special car would take them from the airport to the printing house.

But the proofreaders were masters of making this monotony and hardships an everyday festival of wit.

It was particularly hard during the days of the congresses. Long speeches and reports would be edited from 2 pm to 6 am the next day. Armenpress’s corrections were “interesting.” The official articles were already edited; the page was practically ready to go to print, when a series of corrections would come from Armenpress. Written at the end of Brezhnev’s speech was “applause,” while in the corrected version, “fervent applause” or “fervent, standing ovation.” And depending on how many times they clapped, that many times they would correct it and change the sentence.

After the paper was printed, its first readers were the city’s old Bolsheviks. If they found any typos, they would write to the editor and sign it “a group of friends.” And the mistakes were sometimes serious. For example, once in the headline, in the phrase “in the Soviet city council session” a difference of one letter meant the phrase read “in the shit Soviet…”

And after a long list of political figures, the phrase “and others” became “and other dogs” merely because of a space and a duplicate letter.

Editor Kroyan was very strict and thorough. His devotion to his work reached the point that sometimes he instructed the proofreaders to see if the airplane in the photo was a Tu-154 or Tu-153, to ensure that it corresponded to the text.

The newsroom had its joys. At night, when they, tired, delivered the paper to the printer, the wit would erupt from the proofreaders’ room.

In the newsroom, there was the repat Master Tribune. He was the paper’s publisher. He was extremely devoted to his work. The tired and hungry proofreaders would often eat the breakfasts Master Tribune brought, and Master Tribune would complain to Koryan: “They ate it, they ate it; they’re eating all of it.” When calling Koryan at home and his wife would say he was sleeping, Master Tribune had a habit of always asking, “If Comrade Kroyan wakes up, tell him…”

The young proofreaders had another source of joy: handyman Artash. He spoke in a regional dialect. One time, they had promised Artash a bottle of vodka if he can name three animals in proper Armenian. Artash had thought about and counting on his fingers mispronounced the names of three animals.

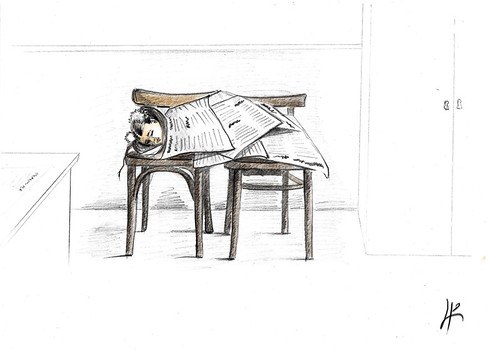

On several occasions, the broadsheets of Sovetakan Hayastan served as a blanket for me, when tired I slept on chairs pushed together. While, at home, I would often take the newspapers and imitating my father, begin to proofread, bringing letters and words to the margin.

When I was young, I thought Sovetakan Hayastan and the cafe/restaurant “Paplavok” were affiliated because several times a day they would go as a group to drink coffee, and for half an hour I would run along the perimeter of the lake. While in the winter, while the proofreaders were drinking coffee, I would roll over on the snow-filled lake and like a expensive parrot would repeat the incomprehensible words and phrases I heard during the day.

On that section of Isahakyan Street, when a cafe began to be built a few years ago, I carefully and fearfully kept an eye on the development so that my precious two big windows won’t be covered, which were my entrance door to the editorial office of the Central Committee’s official paper, the place of my most incomprehensible joy.

Lusine Hovhannisyan

Illustrations by Lily Karapetyan