The obituary as a genre, it seems, has died too. Written now are reviews and opinions about death

“Human dignity shall be respected and protected by the state as an inviolable foundation of human rights and freedoms.” (Chapter 2, Article 14 of the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia)

“Everyone shall have a right to life.” (Chapter 2, Article 15 of the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia)

Nothing about the death of an individual, in terms of rights; that is, about being protected under the law after death.

This is what I mean: information in the media and discussions on the circumstances surrounding the death of a deceased individual should not be left to a journalist’s upbringing, tact, or a thin brochure on journalistic ethics. A deceased individual’s posthumous dignity must be protected if not with the Constitution, then by law from the pretense of offering unsubstantiated, ungrounded claims as precious truths.

Chapter 5 of the RA Law on Media Freedom is dedicated to the rights of journalists. In particular, paragraph 7 stipulates that checking the accuracy of the information provided to a journalist is the right and not the obligation of the journalist.

Writing about a person’s death is a great professional and human test. It’s so easy to appeal to sympathetic pity: to either write nonsense or be cynical or sentimental.

The obituary as a genre, it seems, has died too. Written now are reviews and opinions about death. If an obituary had specific rules, to present the deceased’s life and his scientific or public legacy, well, the motive of reviews about death are completely different: death becomes an occasion for information. The author presents his own personal reflections and theories on the circumstances surrounding the death, sometimes settling his personal score with the deceased. And this is done so openly that readers will subconsciously ask the question “Was the deceased a moral person perhaps?”

On social networking sites, to a large extent, there is no legal restriction: each person decides for himself how to respond to someone’s death. In this case, the style and even silence of each of our response is in the domain of upbringing or worldview and not law.

The situation is different with news outlets, when every sentence must be supported by concrete fact. Media outlets are obliged to be professional and to work competently.

Theater critic Levon Mutafyan recently passed away. His body was found on November 11 in the bathroom of one of the hotels in the center of Yerevan. According to the autopsy, “The death was a result of acute heart failure.”

The Investigative Committee issued a statement, reminding the public that “The right to private and family life of each citizen is defined by Article 23 of the RA Constitution. At the same time, the use and dissemination of information related to the person is prohibited by this article if it contradicts the objectives of collecting information.”

Let’s look at some headlines of articles covering the theater critic’s death. “Levon Mutafyan’s death: A practical joke?” (Hraparak.am). The author concludes: “And now it’s hard to believe that Mutafyan died by his own hand.” Why is it difficult to believe, based on what facts, and why, ultimately, is his death a “practical joke”? No facts, simply an assumption that shouldn’t have had any chance of being published in the press, as it contradicts the simple rules of journalism.

Another headline: “Levon Mutafyan’s mysterious death” (Irates.am). That the facts convinced the author that the death was mysterious, you won’t find that in the story. Note, the facts, not assumptions.

On NorLur.am, even the headline is approximate: “Levon Mutafyan’s body was discovered in Kanaker-Zeytun”. The story states that Mutafyan died “in one of the dormitories found in the Kanaker-Zeytun administrative district.” Clearly erroneous information.

Yet another headline: “Mutafyan wasn’t alone in the hotel” (Hraparak daily newspaper). Yet again, the story contains assumptions and not a single fact.

BlogHay.ru wrote: “The fact is that the internet has been flooded with various news and comments, especially connected to the theory of L. Mutafyan’s being found alone in the hotel. The public [?] doubts while some news outlets, citing their sources, declare that some young person accompanied the late theater critic to the hotel adjacent to his apartment, which, by the way, is found in the vicinity of Komaygi*.”

The author of this story after all this concludes: “What gave rise for people to have such opinions, perhaps, is hard to imagine, but one thing is obvious: there’s no smoke without fire.” But the “no smoke without fire” idiom is as accurate as the proverbs “A fool may throw a stone into a well which a hundred wise men cannot pull out” and “Measure thrice, cut once” are true.

Not even the Constitution nor the Law on Mass Media help in being insured against such reports.

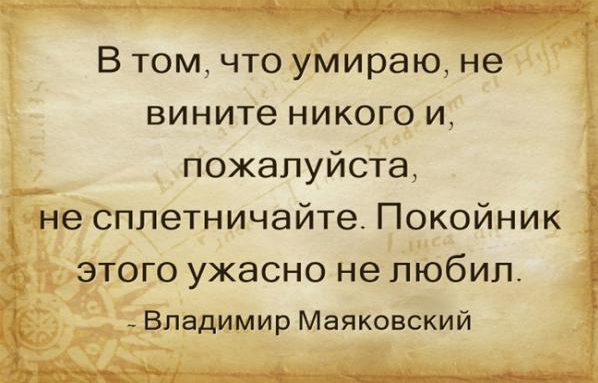

After all, before writing about a deceased individual, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to recall Vladimir Mayakovsky’s note written before his death:

“To everyone:

Do not blame anyone for my death, and please do not gossip. The deceased terribly disliked this sort of thing.”

Lilit Avagyan

*Komaygi, officially the Children’s Park, is a public park in downtown Yerevan where sex workers, especially trans women sex workers, are known to work.