Perhaps now is the time when the media sector can no longer be neutral and balanced, since it has an interest: it wants people, prior to voting, to ask questions

The December 6 referendum, as a result of which it will be clear with which Constitution (current or amended) the Republic of Armenia will live hereafter, created an active work area for the media.

Some TV channels not only made the constitutional amendments a topic of news and talk shows, but also launched new projects. ArmNews TV’s marathon reality TV show, for example, is presented as large scale and “unprecedented.” The show will broadcast the campaign with the participation of those on both sides of the debate throughout the country for 20 consecutive days. Representatives of political forces are meeting and will meet different people, presenting the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed amendments, and all this will be broadcast live — simultaneously in both directions (from the north and the south).

Watching the programming on the first day, one noticed that residents, having their moment in the spotlight, talk about their daily struggles, achievements, the younger generation, historical and cultural monuments, and thank various state officials. And then there were a mixture of speeches with a medley of issues: on gas, schools, living in close quarters, and so on. In short, it was stated that even though people live well, they want to change the Constitution so that things will be better. The televised conversations were sometimes chaotic and sometimes structured in a way that was common during Soviet times. When Armenia was not independent. And when people from Yerevan visited the village, and the village was happy.

A new political show was established also during the term of the new management of the Public Television of Armenia. The show, called Yerankyuni (“The Triangle“), was widely received not so much because of its content, but because of its ambiguously-perceived host (Minister of Education and Science) and his party affiliation. The Triangle’s debut episode was announced as a nod to the draft constitution, but it more so remained in history with the intense and loud character of the host.

Minister/host Armen Ashotyan asked this on air: “Why doesn’t professionalism of the media sector correspondent to today’s challenges?” And then: “Can’t we differentiate between mass media and intellectual news outlets?” [saying “intellectual” twice: first using the Armenian word, then the Russian].

It’s hard to say what sort of criteria an “intellectual” news outlet should have (this is probably more so from the science and education sector), but all those working in the media sector are now trying to present the package of constitutional amendments in such a way so that it becomes understandable for the audience. There is particularly a need to decode the “underwater” dangers and obstacles of the amendments, and in some cases to interpret the complex legal turns of phrases and abstruse statements. A good example of such decoding is the Boon TV series [in Armenian only], which briefly touches upon the current and proposed amendments. The Boon series, of course, is not mass (media), but it’s definitely “intellectual”.

The media often assumes the role of decoder/translator, if, of course, chief editors have such an aim. If they don’t, they place the emphasis on emotive and so-called patriotic and philanthropic exhortation. In the Yes–No reality show, for example, often heard is “dear people,” “Let me take your pain away” [a direct translation of a common empathetic expression] and “We’re here to solve your problems.” This style of addressing the audience creates an illusion of the masses, though who is solving whose problems remains unknown. And why those problems arose, in general. Or, why those problems can’t be solved with the existence of the current Constitution.

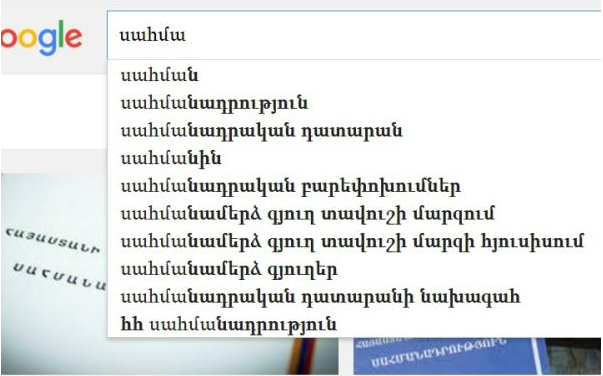

Being for or against the draft of the proposed constitutional amendments is conditioned by the questions of the audience (the electorate). The more the questions and interest, the more the difference between “yes” and “no” will become clearer. And the choice will become that much more meaningful.

Naturally, the media at least during this time should work to increase the number of those asking questions. Exhortation and coverage differ from one another with specific (not rhetorical) questions and specific (not unclear) answers. A specific question must be addressed to a specific person and receive a specific answer.

And since the campaign of the referendum on the constitutional amendments has already begun, many state agencies and civil society groups are trying to both provide answers and exhort up front. And news outlets have found themselves in between them.

Perhaps now is the time when the media sector can no longer be neutral and balanced, since it has an interest: it wants people, prior to voting, to ask questions. To see a likewise coordinated “No” next to the intellectual and coordinated “Yes”. So that the choice is not only of the masses, but also intellectual.

Nune Hakhverdyan