The Istanbul Biennial is one of the most interesting platforms of contemporary art that tries to make its unique voice heard in a world whose pulse is one way or another connected to the public and the private, the national and the international, the state and the family, the expression of free will and the compulsion of models of social behavior.

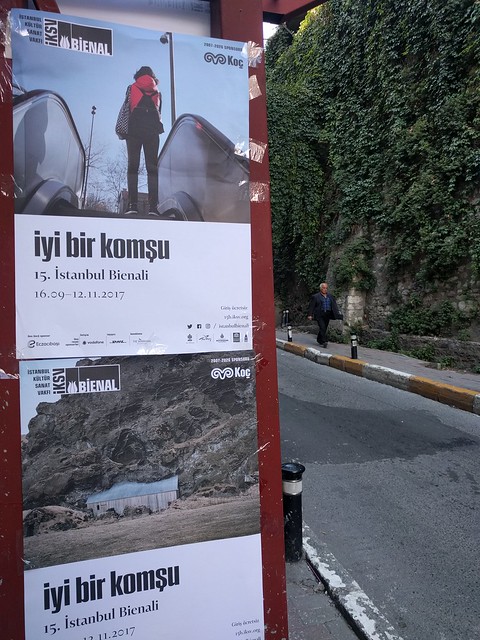

The idea behind the 2017 Istanbul Biennial is very intimate and at the same time demonstrative in its simplicity: “a good neighbour.” And not only have various artists been selected and exhibits, organized under this heading, but the city has been shaped under it too.

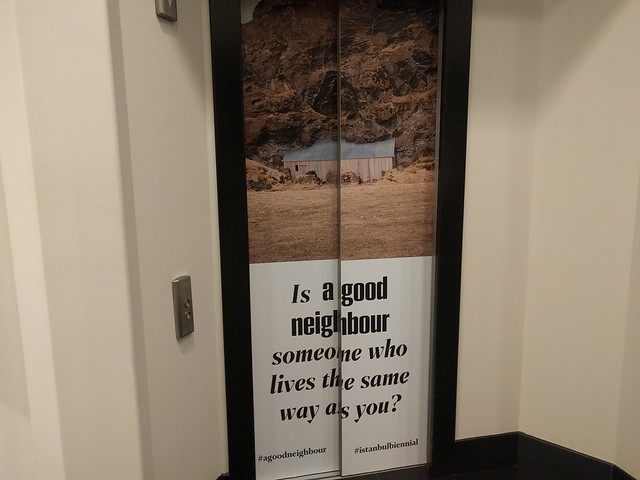

Photos captioned “A good neighbour” appear in different venues, mainly in the form of a question. The questions are branded in rows in the subway, in public squares, on the streets, on elevator doors, in cafés, and in other public spaces.

“What is a good neighbour?” The biennial offers different variations of this question, sometimes small and unimportant, sometimes rhetorical or sorrowful. For example: Is a good neighbour — “a stranger you don’t fear?” “your friend on Facebook?” “reading the same newspaper as you?” “someone with no WiFi password and a strong signal?” “leaving you alone?” and “cooking for you when you’re sick?”

Humorous questions are also many. The curators of the 2017 Istanbul Biennial generally are humorous.

Michael Elmgreen (Denmark) and Ingar Dragset (Norway) of Elmgreen & Dragset are artists who are curating a major exhibit for the first time and have approached the task through a narrowly personal, even household questionnaire format. According to the concept, the questions have to prompt the viewer and also the reader (in this biennial the texts are many, even a special book is published with the title Stories) to search for answers.

In the year preceding the biennial, polls and “intrusions” were organized in the everyday life of Istanbulites, resulting in the selection of 40 symbolic questions, which through the format of a performance recall different characters from 8 to 80 years old. These questions having wide social coverage are both light and extremely serious, but almost all are optimistic.

And this optimism, which is injected in not only the artistic works, but also short videos, though interesting and sensual, in any case is extraordinary.

Many things in this year’s Istanbul Biennial are done or said not out loud but in whispers. Maybe that itself is the reflection of reality: art in Turkey is trying to find its tongue, maneuvering between freedom, censorship, and self-censorship.

Unlike the 2015 biennial, titled “Saltwater,” which had included a noticeable and very striking Armenian presence, this year there was no Armenian trace. “Saltwater” was about Istanbul, which opens up to the viewer as a tangle of global, universal questions, including as well, daring to speak about the Armenian Genocide in the year of its 100th anniversary.

It seems that the question “What does it mean to be a good neighbour?” could be woven into the lifestyle and concerns of different ethnicities living in Turkey today. But the biennial chose a less provocative (politically speaking) and more personal (emotionally speaking) approach. Meanwhile the tagline was a good opportunity to dialogue also on that level.

The Istanbul Biennial’s main organizer is Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV), whose Exhibition Coordinator Elif Kamışlı had this to say:

“I agree that it was a good opportunity. But curating an exhibit doesn’t mean making a checklist and inviting artists from all the neighboring countries such as Greece, Bulgaria, or Armenia. The curators selected artists based mostly on aesthetic choice, because they have a very strong and prominent visual language and have been working together for 25 years. And they wanted to keep that language in the exhibition when curating.”

The curators have said that they want to turn the biennial into a platform for dialogue, which is particularly important today, when everywhere national movements arise and wars are going on. They expressed a wish that the three-month-long biennial become a space where different opinions, views, and communities come together. And as a result, diversity is emphasized.

A good neighbor is a person independent of ethnicity, age, and sexual orientation, whose value is felt only by those next to him (well, it’s not like you’ll become a good neighbor for yourself).

But for a person (or state) to be considered a good neighbor, first of all we need to recognize, to acknowledge him. Not invent, imagine, or endow him with the aspects you want, but really know him. Recognizing is the most difficult…

The concept “a good neighbour” at first glance is daring almost to a revolutionary degree, but at the Istanbul Biennial it had been deprived of political or historical context, and mainly arrived at the conclusion of family, a warm corner, the accumulation of memories, and lyricism.

The wars (present and expected), the chaos that has caused enormous numbers of human migration, death, and deprivations; historical excursions; social responsibility; and media reactions are presented at the Istanbul Biennial as the start of a new romanticism.

According to many artists, permanent are the scent of the home and favorite dinnerware, the lovingly furnished room (which is also mobile and always with you, though in your mind), the correspondence, the feeling of kinship. That is, all those objects and feelings that help you to shelter yourself in your own micro-universe.

Elmgreen & Dragset have organized the biennial with fragile personal stories, confident that “the personal can become political.”

The small, the personal, and the private are hiding places and simultaneously the start of resistance (what to do if your neighbor isn’t good? Maybe first you must try to become a good neighbor to the person next to you?).

The whispers about this very delicate subtext are really very low. The biennial’s first layer is optimistic, easily perceived, and far from a political agenda.

“Our curators have chosen a language that is not connected with heated political debates because that is harmful for art. It becomes rhetorical, when art repeats itself all the time. All the time… Of course, if you’re looking for direct propaganda language, you will hardly find it at the biennial. Everything depends on how you read the works, how you connect with them,” says Exhibition Coordinator Elif Kamışlı.

Art never answers; it just raises questions.

The Istanbul Biennial has fragmented the questions and sent them to different corners of human existence (social media accounts, the habit of drinking coffee together, fear of foreigners, personal psychological traumas, and a thousand and one physical and subconscious layers). As though the questions are puzzles, which to piece together you have to exert effort and excavate the current, the topical from the first decorative layer.

And this is seen very well from the photos, which are the business card of this year’s biennial. A very symbolic and beautiful business card.

Photographer Lukas Wasserman went around Istanbul talking to people and photographing. As a result, his works have appeared as billboards on the streets of not only Istanbul, but also Moscow, Havana, Delhi, Chicago, Manchester, and Sydney. This was done to show that searches for the formula of a good neighbor are familiar and important in different countries, and art can be so mobile that it establishes a connection between cities and their residents.

The Istanbul Biennial with the alluring heading “a good neighbour” tried to send hope and a positive message to the world. For the biennial’s 58 artists, mainly young, their own biography is raw material with which to create.

Making the move from the personal to the general and not getting lost on the way is very difficult. There are times when the gift of simply being together and getting pleasure from this act should not be underestimated. Sometimes this is a bigger political act than manifestos, rallies, and loudly proclaimed statements.

This year’s Istanbul Biennial can be viewed also from this philosophical perspective.

Particularly if holding rallies and street demonstrations has become difficult. And so that you don’t become silent, you prefer to whisper about what’s important (even if only in your neighbor’s ear). And if there are two, there is also dialogue.

Is it romanticism? And why not?

Nune Hakhverdyan

The views expressed in the column are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the views of Media.am.

Add new comment

Comments by Media.am readers become public after moderation. We urge our readers not to leave anonymous comments. It’s always nice to know with whom one is speaking.

We do not publish comments that contain profanities, non-normative lexicon, personal attacks or threats. We do not publish comments that spread hate.