The focus of this year’s Tvapatum media conference was media management. In this fickle and volatile situation, when we’re bombarded with information, a review of media–audience relations is a vital requirement.

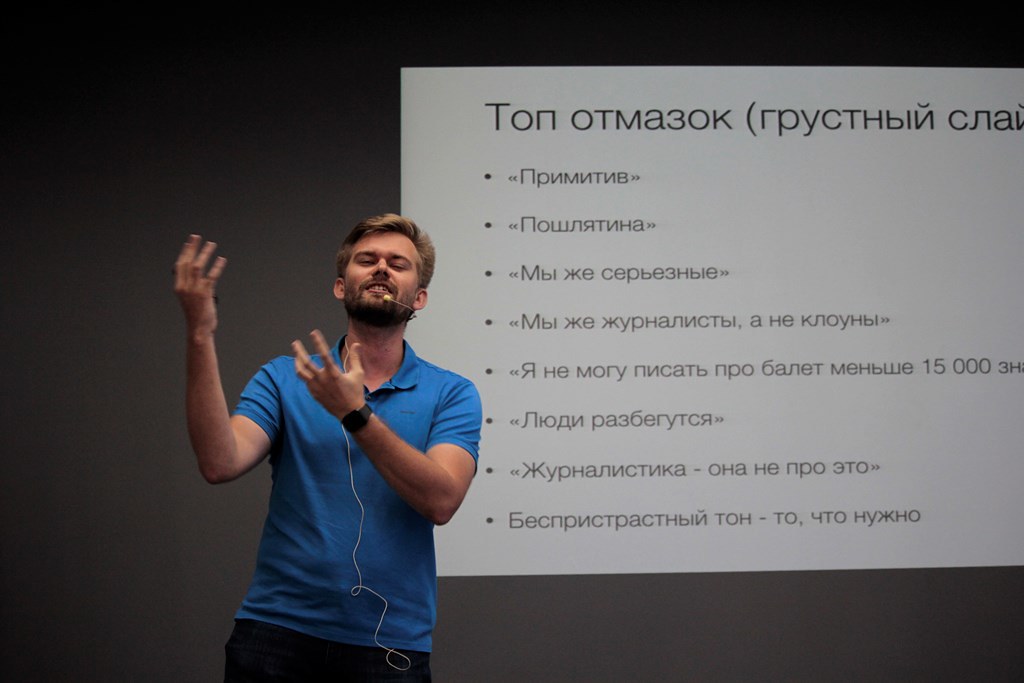

Media trainer Vsevolod Pulya’s master class was about these bilateral relations (trust, connectedness, as well as dependence, and even, love).

Russian journalist and producer, editor-in-chief of Russia Beyond The Headlines Vsevolod Pulya advised not to forget that a media outlet’s competitors are not other media outlets, but all media content.

“Journalists today write for people who are constantly distracted. And if in the process of reading your story the reader gets a message from his mother and digresses, then we have to compete with also the mother,” he said.

Is the audience always right?

Let me put it this way: you can’t ignore the audience. Of course, the audience is diverse, massive, and often incomprehensible. But if we’re talking about a specific publication’s target audience, then yes, it’s always right.

It’s just that as a chief editor and media manager, you have to understand what kind of audience you need and then adapt your product to its demands. I’m talking about customizing, transitioning from infotainment to direct impact journalism.

In demand is a simple, accessible, and happy newsfeed, regardless of the poignancy of the topic. Also in demand are journalists who write simply, concisely, and accessibly.

The tempo has changed, people read quickly. If they can’t understand the deep hidden subtext, they simply won’t read to the end, they’ll see only what’s on the surface. In any case, the packaging of the information must be attractive.

It seems to me that rather, you have to explain to the audience, help it understand. And it’s no coincidence that one of the formats most in demand is explanatory journalism.

It’s better not to hide your main message and emphasize its ambiguity, but to clearly and accessibly explain what happened, in what context, what it means, and what needs to be done.

If you know your readers well, then you know also their concerns, and you want to help them understand the essence of the issue.

For example, we try to explain the logic behind Russian officials’ decision-making, what interests Russia has in different regions. Or, why people got out on the street on June 12 to protest.

We explain without the consideration that there’s one inimitable point of view. We want our readers to make better sense of decisions and processes adopted in Russia.

Journalism cannot exist in a vacuum, cut off from the audience. If there’s no audience, there’s no journalism.

To what extent is the media’s independence affected by financial sources? In Russia and Armenia, there are media outlets that wouldn’t have an audience if they didn’t have money.

Of course, media outlets receiving state support have seriously distorted Russia’s market.

I myself work in such a media outlet; it’s just that our target audience is abroad. It’s hard to picture a publication that has wide international coverage and is self-sustaining. In principle, no such thing can happen in Russia. To be honest, I’m not familiar with such examples abroad either.

It’s important for the advertising market to work sensibly, without deviations. Publications that receive state funding also operate in the commercial market, and attract also advertising money, which could’ve been directed also to independent, private companies.

Yes, this is a problem.

To what extent does television affect Russian society? Perhaps it not only distracts, but also helps, by raising issues.

We don’t compete with television, especially the federal channels. But, of course, television continues to be the main source of information in Russia.

In the TV sector, the state has the monopoly in getting across the meaning and messages it wants. On the other hand, we see that Russia is a country connected to the internet in quite a large volume, which means that a wide variety of opinions, investigations, and blogs is available.

That is, there is access; the issue is the audience being educated and literate. It’s important to be critical of everything the television describes.

I believe media literacy needs to be taught in schools. Children should know that you shouldn’t unconditionally trust what the TV screen tells you.

At the Faculty of Journalism of Moscow State University, I teach a special class during which time we often talk about media literacy. And with not only university students, but also schoolchildren.

Schoolchildren are a completely different generation; their critical thinking is at a completely different level than adults’.

What is particularly characteristics of the generation of 14–16 year-olds?

They’re used to living in conditions of information overload. And thanks to this, they’re better able to build filters, understanding what information should reach them and what should be bypassed.

Perhaps this helps young people see the world more completely, which their parents do with difficulty.

14–16 year-olds know more, search for more, and read more.

Of course, there’s the risk that this generation will become a slave to algorithms, social networking sites, and news aggregators.

We all know that there’s the balloon phenomenon: when someone clicks on the Like button or comments on that which corresponds with his own opinion, then some time later, this or that online service undoubtedly begins to show him only news that confirms that viewpoint.

Widely reported was the case when during the US presidential election, Clinton’s and Trump’s supporters shared their Facebook accounts with each other, and each group’s “eyes opened.” Many confessed that they didn’t know there was another reality. That is to say, neither Trump is that bad, nor is Clinton that devious.

The new generation, on one hand, is better prepared for life, but, on the other hand, it may fall victim to algorithms. And we have to reckon with this situation.

During the Tvapatum conference, this idea that today is the best time for journalists was frequently stated. Is it really so encouraging?

What’s encouraging is that today anyone can become a journalist. But for a professional journalist, this is a serious challenge.

If in the past, to tell the story of an excellent carpenter, you had to send a journalist to him, now the carpenter himself opens his own blog, gathers an audience, and talks about himself. Today everyone’s an author.

What happened was an explosion of original stories. From the years of human existence (from ancient times to the end of the 20th century), there have been 300 million authors in the world who left their own mark.

But now, the tools of self-expression are available to a few billion people, and all are potential authors.

On one hand, that’s astonishing; on the other hand, it’s terrifying because each one can turn himself into media. There are now bloggers whose audience exceeds that of federal publications; meanwhile, hundreds and thousands of people work there and large sums of money are invested.

How can these conditions not inspire real journalists? Of course they inspire them, because a journalist has the same opportunities as a carpenter or a shepherd.

That is, a journalist must gather around him as large an audience as possible and try to influence their views, promote cultural growth. And, of course, get feedback from the audience and recognize it.

For me personally, this is the most important. When I see real, living people behind statistical data (traffic, visits, views, and so on), I get a huge surge of adrenaline.

If they respond to you and comment, if they’re grateful to you, even if they criticize you, you understand that the audience is not indifferent. And so your work wasn’t meaningless; you provided new knowledge and you amused.

Being a journalist is not only inspiring, but also just wonderful.

Interview by Nune Hakhverdyan

Photos by Gagik Aghbalyan