American photographer Adriane Ohanesian is one of those documentary photographers who prefer to work in dangerous parts of the world, to describe what’s happened in a fresh and unhurried way and sometimes through people on the margins.

Adriane went to Sudan for the first time for a short time but stayed there for two years, documenting South Sudan’s civil war, the formation of a new state, and the lives of millions of victims and refugees, and creating impressive photo stories.

Later she also photographed the clashes in Burundi and Myanmar. Her work has been published by Al Jazeera, The Wall Street Journal, National Geographic, and TIME magazine. And her photo series have received awards from National Geographic, World Press Photo, and Getty Images Emerging Photographers.

In Armenia, Adriane tried to reinterpret her Armenian roots. “I would like to spend more time in Armenia, travelling and photographing,” she said at an I Am the Media meeting organized by the Media Initiatives Center [also responsible for this site].

Deceive neither the audience nor yourselves

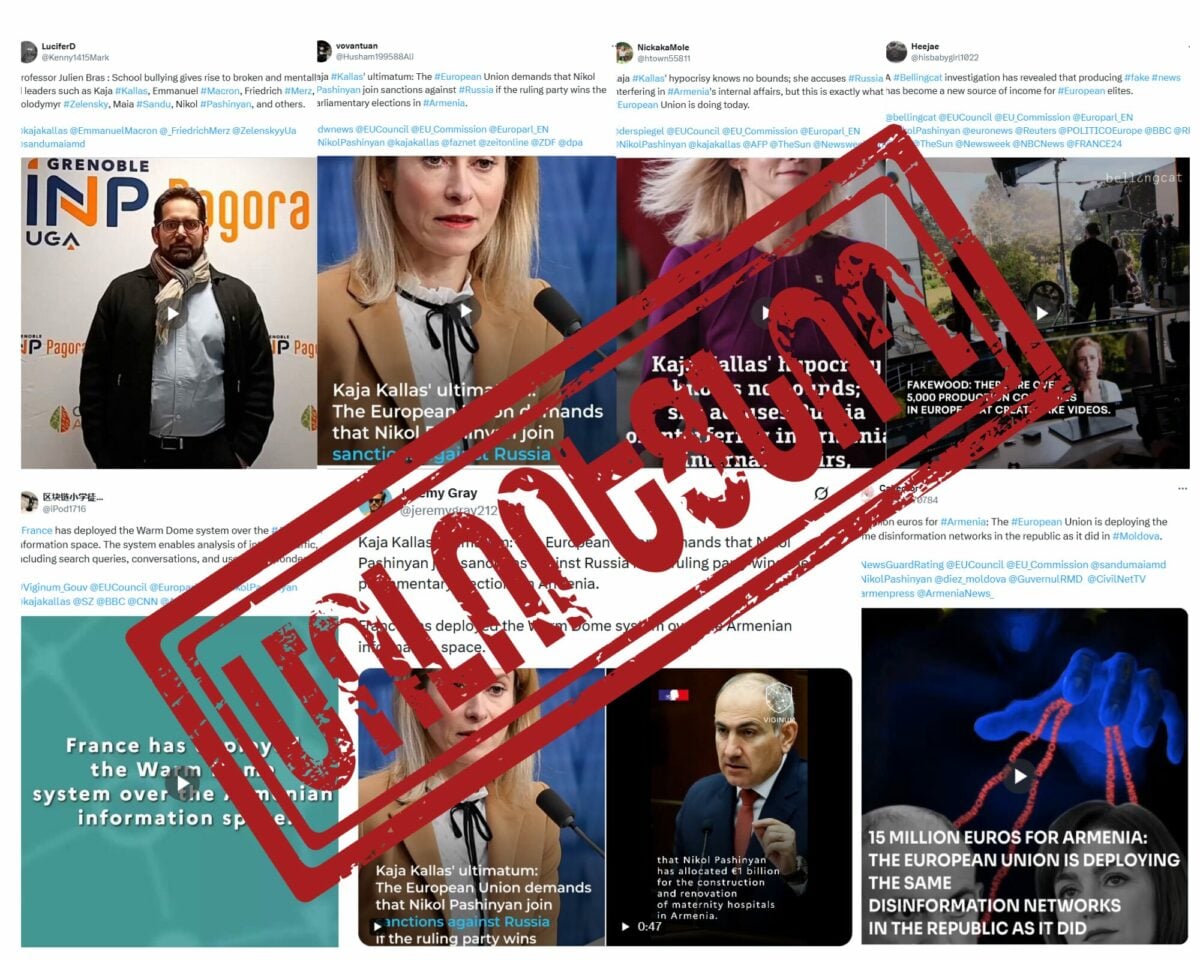

Now anyone can take a photo. And do anything with it. People can put text on it, crop it, do Photoshop. And more and more this will be an issue for professional media.

As a professional, I understand that main thing is for people to trust images. I think we lose that trust with all those images that come out from social media. That frustrates me because people who do work for the media seriously are kind of pushed aside in all this information coming out.

We are just trying to be honest about what we are doing, what our intentions are. Who are you? Are you a journalist or documentarian? Let’s not kid ourselves.

Photographers often interfere with reality, add, convey sharpness. I’ve always wanted to be honest and don’t add anything. I show reality as an official document.

I want my photos to be used at the time when they were taken. Or at least some time later, as documentation, that will help gain an understanding of what happened in the recent past.

Of course, I also try to make my photos visually attractive. I organize and clean my photos, working very slowly. I always talk at length with people, not rushing them. I wait till I get things the way I want, to arrange a frame. I don’t just snap away. I think I make not an emotional, but a more conscious choice.

I try to contain what I see, to explain what has happened in one frame.

As a photojournalist, you have to be on the scene before everyone and leave the scene after everyone. I left South Sudan after everyone, and I go back regularly, since I appreciate and love the people there. Their hospitality, kindness, and humour propel me to return to Darfur again.

In South Sudan

In 2010, for the first time I went to Sudan, where a referendum was to be held. I stayed and worked there for two years, but I didn’t publish any photos. In photojournalism, generally, the process and the result are not the same. Initially, I would patiently send my photos to various media outlets, but I didn’t receive a response.

I was forced to work for different NGOs, saying, if you take me with you, I’ll take some photos for you. But now I collaborate with different media outlets and organizations, now for pay.

When I first went to South Sudan, I had no backing from a media outlet; I went with my own funds. It was hard working there. Apart from travel and transportation costs (which were quite a lot), I needed to settle security issues. I was a freelance journalist, I had no agreement with any media outlet, since I myself didn’t know what to expect. Many said that going to South Sudan was a dumb move.

Especially the fact that you’re a foreign journalist, that immediately exposes you as a specific target. The government targets journalists in particular and in different ways prevents them from entering the country. But I didn’t regret my decision for a minute.

And since I went of my own accord, it turned out that I had entered the area thanks to the rebels, because the government army doesn’t control anything there. That was a difficult journalistic decision. But you need to always remember that as journalists we’re not party to the conflict.

In South Sudan, I was photographing not the war but people who lived in a conflict situation.

People live in extremely dire conditions, in caves and pits, and are constantly exposed to air strikes. The government troops’ bombs fall on people whose only wish is to live peacefully and safely. There are no basic living conditions. Nor hospitals. Also living and working there is 2017 Aurora Prize Laureate Dr. Tom Catena, whom we’ve often met in South Sudan.

During every bombing, the children hide in the pits or between rocks. It’s hard to convey people’s hardships and tragedy. If, for example, a high-rise building in the world catches fire, it’s possible to convey the entire dramatic situation in a photo, but when a small African hut is burned and two goats and a camel are harmed, it’s hard to convey to the viewer the feeling that the family living in that hut actually just lost everything.

Many people don’t know what’s actually happening in Sudan.

Ultimately, people don’t become refugees of their own free will. I don’t accept the one-sided opinions on the refugee crisis. It’s important to understand that many Sudanese would want to return to their homes; it’s just that those homes no longer exist.

People want to meet their basic needs: water, food, security, peace. Health and educational problems become exacerbated when the government doesn’t provide these basic necessities. The war in Sudan is in the name of not convictions but life.

And the war doesn’t end for the reason that the country is closed to journalists. The media practically doesn’t cover what has happened, since it’s a dangerous area for journalists. They’re arrested, tortured.

Documentation with an insider’s and outsider’s view

It’s hard to orient oneself also for the reason that what happened isn’t archived, since the conflict hasn’t been covered for years. It seems we have to reveal everything from zero.

Civil war has ravaged South Sudan. There’s no longer any information about thousands of people: they’ve either been killed or fled to areas under UN control. In the first few years, I tried to map for myself a few settlements, inquiring about the number and movement of residents.

It’s hard to convey instances of large-scale destruction and sexual violence. Every time you’re faced with a choice.

Sometimes local residents think that foreigners (doctors, journalists) are saviors who miraculously appeared. And it would be great if there were many local journalists, since they’re the ones who possess all the information and can change the situation.

Of course, foreign journalists have a fresh view and are better prepared, and internal freedom and courage is required of them, but only local people can make change. For this reason, I place great importance on local media.

My job is kind of like international help. Peoples always have good intentions but nothing is stronger than movements and opinions coming from the population.

The last time I was in South Sudan was the summer of 2016. A journalist with me who was there for the first time said the situation is so bad, I’ve never seen such an awful situation. And I was walking around and just thinking: everything looks ok, two years ago it was much worse.

I didn’t see anything new and I wasn’t surprised; it seems I had become accustomed to a situation that in no way is normal. As a photographer, you always have to keep your view fresh and be ready to see with eyes anew. Check yourself with photography, so to speak, and try to see people and the situation as though you’re seeing it for the first time.

Be ready for the new

It’s hard to maintain freshness without getting bored or acclimatizing. In Yerevan, the singing fountains were new to me. Your view has become used to seeing these fountains every day, but I saw them as a revelation. The fountains and the old buildings are always there — they surprise me, but they no longer surprise you. And the sun always rises from behind the same mountain. You see this every day.

I hope that next time I will photograph Armenia, and not just a part of Yerevan.

I now live and work in Kenya, which is a peaceful place for me. But, all the same, I regularly go to South Sudan, since the stories I did in Darfur are always with me and they have to continue and develop.

It seems I feel that I’m still needed. I still have a role to play in that country.

Nune Hakhverdyan

Photos by Sona Kocharyan