Both the World Life Expectancy report and the Armenian Ministry of Healthcare’s angry reaction, and the WHO’s figures differing from the healthcare ministry’s can become an opportunity for information — for journalistic investigations

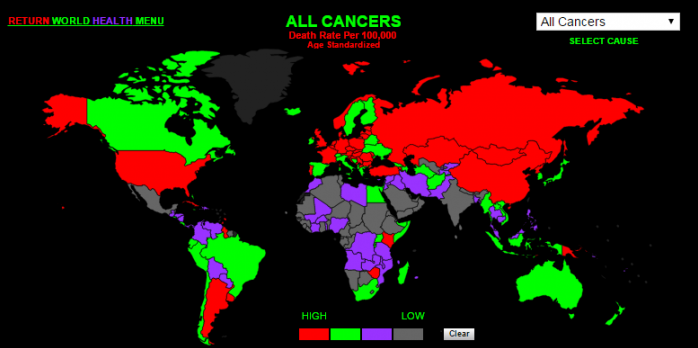

Spreading like wildfire in local Armenian media on January 15 was information from the website World Life Expectancy on the mortality rate of cancer patients in 172 countries. According to the news, in Armenia, 229 people out of every 100,000 die from cancer.

Five days later, on January 20, Armenia’s health minister deemed the news “absolutely false,” remarking that there are “corresponding figures published by the World Health Organization (WHO).”

Director of the Armenian Ministry of Healthcare’s National Institute of Health Aleksandr Bazarchyan was also skeptical of the information from the World Life Expectancy site, saying that he studied the website and didn’t notice any links to articles, authors’ names, or other data necessary to arrive at such a conclusion.

It’s true: anyone visiting the site will be convinced that the figures are without concrete references.

The local media rushed to publish this top news story, adding various comments, fears, and assumptions why it’s very likely that this news is true: mining, polluted air and water, food laden with preservatives, and so on.

It is expected in such sensitive news cases (especially from us journalists) to subordinate the desire to be first to professional integrity, ensuring at least two reliable sources of information. That is, it would’ve been smart to first contact the World Life Expectancy website and ask them to substantiate the numbers, which, by the way, local doctor Byurakn Ishkhanyan did [AM].

Second, to contact the Ministry of Healthcare and ask them to prove why the World Life Expectancy figures are “absolutely false.”

To be the country in the world with the highest cancer mortality rate is a terrible statistic. According to the healthcare ministry data, the cancer mortality rate has almost doubled between 1990 and 2013. In this case, we don’t have to go far: each of us has our own unfortunate statistic.

However, is it even possible to get an accurate statistic of cancer patients?

The main tool for statistics is simple calculation. Oncology services are free in outpatient clinics (“polyclinics”). Presumably, people with complaints rush to get initial assistance from these medical institutions. Patients diagnosed with cancer are directed to second and third professional institutions: to undergo surgery or get other treatment.

Polyclinics calculate and send to oncology centers the statistics they have in their possession. The exact number of cancer patients, however, is practically difficult. And in the information provided by Ishkhanyan, the World Life Expectancy site also mentioned this.

According to figures from Armenia’s National Oncology Center, for example, 1,274 cancer cases were discovered posthumously. These cases are included in the overall statistics, but again they can’t provide accurate statistics. There are no morgues in the villages. Each village has one expert, whom calling a ‘doctor’ is an exaggeration. The service costs 30,000 AMD. The embalming is done in the home — with all the ensuing consequences.

I’ve witnessed this sombre scene twice in the village of Koghb. That is to say, there are no statistics on the actual cause of death for people who die in the villages. There, everything is approximate and not professional.

The other fact that also speaks against getting an accurate number are medical errors. That is, the doctor provides a cancer diagnosis, sends the information to the relevant government department, but it’s not cancer at all. Take for example a close friend of mine, a doctor by profession, who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, told to understand her situation and spend the rest of her short life with her family by a doctor known as the best oncologist in the country. In Moscow, the diagnosis was disproven: it turns out she had an ovarian cyst. My friend got married and now has two wonderful children.

It was astonishing, the information disseminated after the World Life Expectancy news that the number published on the site can’t be based on the WHO’s figures because the most recent data is from 2012.

It’s enough to visit the WHO’s official website, where there is information on cancer mortality rates for Armenia and all the other countries. And the 2015 figures will be published in April.

According to the WHO data, in 2014, Armenia’s population was 2 million 969 thousand. There were 37,000 deaths that year. Of those, 22% (9,100 people) died from cancer.

If we compare with Armenia’s neighboring countries, in 2014, the cancer mortality rate in Azerbaijan was 18%; in Georgia, 13.4%; in Turkey, 21.6%. In this instance, we undoubtedly are leading.

According to 2013 WHO data, Armenia had a population of 2 million 977 thousand. The cancer mortality rate was 22%. Whereas in 2012, 8,100 in Armenia died from cancer. But in this instance, too, not everything is clear.

The healthcare minister advised journalists to take the WHO figures as their basis. But these figures differ from the Armenian healthcare ministry’s figures. According to the ministry’s ‘mortality chart‘ [AM], 5,685 people died from cancer in Armenia in 2014 (remember, the WHO figure was 9,100) (Table 1.6, p. 21). The difference is considerable: 3,415.

In 2012, according to the aforementioned ministry chart, 5,607 people died from cancer in Armenia (recall, 8,100 people, according to the WHO). In this instance, too, the difference is not so little: 2,507.

Basically, three different organizations — Armenia’s Ministry of Healthcare, WHO, and the World Life Expectancy website — provided three different numbers for the cancer mortality rate in Armenia for the same period.

According to the WHO, information on infectious diseases and cancer is limited in Armenia, which leads to frequent diagnosis errors and delay in patient referrals. In addition, Armenia doesn’t have a cancer registry and mortality rates fluctuate.

The healthcare ministry has a national program on prevention and early detection of cancer, but it’s hard to call such programs effective, since according to the National Oncology Center’s data, about 46% of cancer patients in Armenia are diagnosed in the 3rd or 4th stage, which makes treatment difficult or impossible. By the way, the problem is not only socioeconomic, since financially solvent patients also see a doctor late.

Both the World Life Expectancy report and the Armenian Ministry of Healthcare’s angry reaction, and the WHO’s figures differing from the healthcare ministry’s can become an opportunity for information — for journalistic investigations. In any case, detailed coverage of each of the numerous issues related to this topic might perhaps contribute to a change in cancer statistics. Whereas the publication of such scales without factual grounds might lead to an increase in an already high number of nervous disorders.

Lilit Avagyan