1988 was a crucial year for Armenia. The year began with a huge nationwide uprising and became a year with the need to renounce the Soviet past and build a model for the future. The Movement had begun.

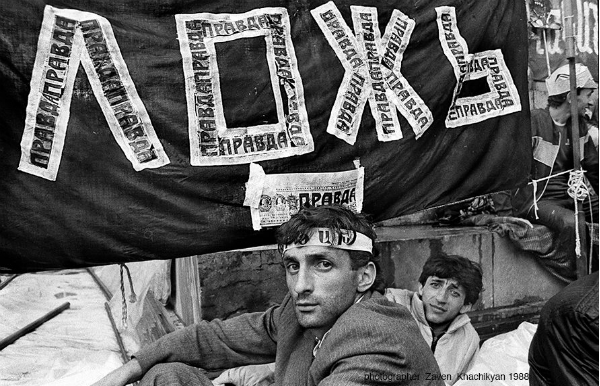

Events developed quite rapidly; people united, took to the streets and introduced to the public agenda such issues (freedom, independence, the self-determination of Artsakh, environmental, and so on) to which the Soviet propaganda machine was unable to respond.

That heavy and rigid machine could not allow an undesirable outpour of information, since every unplanned event was considered a deviation and condemned to silence.

Though perestroika (reformation) was declared, traditional censorship, dictated by Moscow, continued to operate in Soviet Armenia.

The concept of Glavlit in the media and publishing sector was abolished in 1991, but until then, any information about public protests or demonstrations passed through such strict filters that as a result, the news was simply ignored and disappeared.

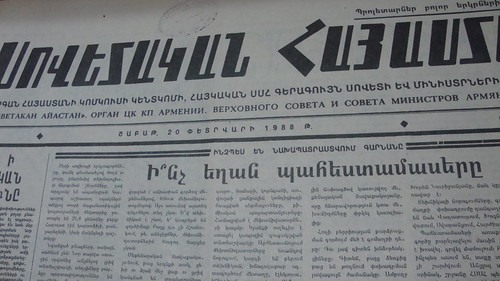

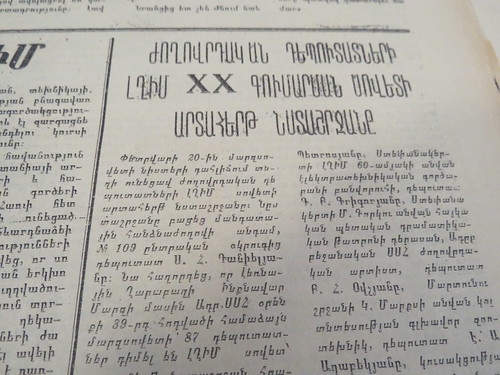

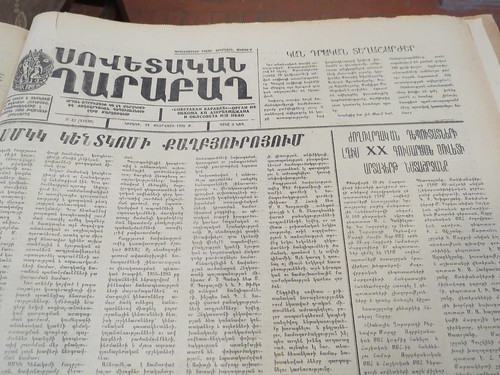

This is how the front pages of the February 20, 1988 (the day symbolizing the start of the Movement) and subsequent February 23, 1988 issues of Sovetakan Hayastan (“Soviet Armenia”) looked: everything continued to be depicted as part of a normal, predictable, and bright Soviet present.

On February 20, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast in its regional meeting adopted a decision to transfer the region from the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic to the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. Sovetakan Karabakh (“Soviet Karabakh”) published the news in a special Sunday issue (below).

However, Armenia’s press remained silent. In February 1988, a powerful social movement was born, but the media worked according to the unwritten slogan “We don’t report it, so it doesn’t exist,” which was firmly rooted over several decades, but in this new situation only raised further waves of protest.

We won’t find news of marches, hunger strikes, rallies, or student sit-ins in the press of those days. Messages and appeals by high-ranking USSR officials were the only coverage. See, for instance, this February 28 appeal by Mikhail Gorbachev (below), which was published during the Sumgait massacres and the escalating rallies in Yerevan.

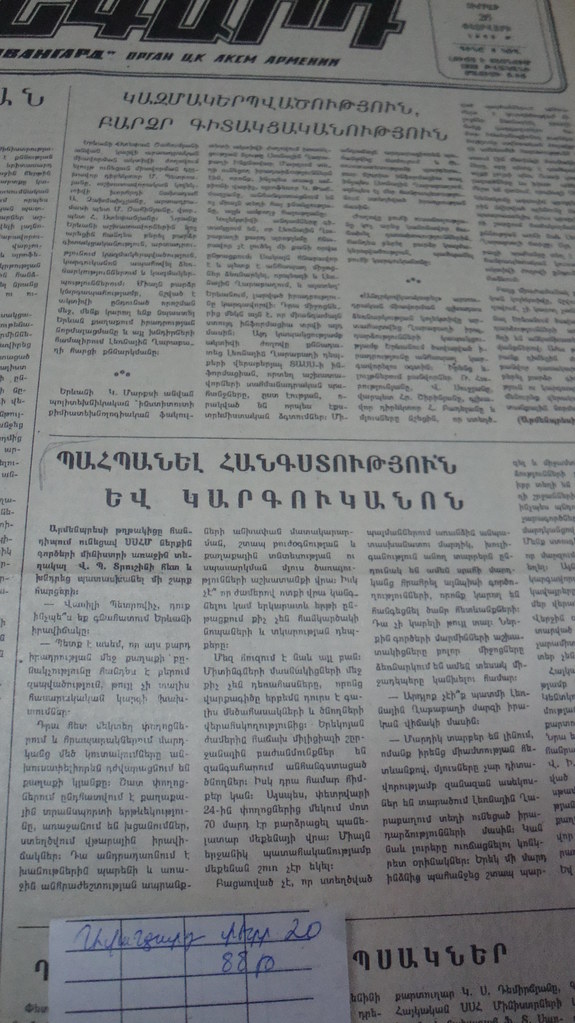

If the official press even reacted to the incidents, it did so through a mediated and peremptory approach. The newspaper Avangard (“Avant-garde”), for example, on February 29 called for order (though for naive readers it remained unclear why this was needed especially now, since the background on the rallies wasn’t mentioned in the paper).

Through the lips of a Russian official we were told that the participation of teenagers in crowded rallies was impermissible and we were warned of cases of seizures and illnesses that can occur when one stands for too long on his feet. And, of course, we were informed of hooligan provocations and keeping the situation in Karabakh under control.

The demonstrators were severely criticized; the propaganda machine barely had time to deny the reality and call for friendship between peoples. Introduced in Armenia’s press were the opinions of Azerbaijanis who appealed to remain friendly and control the situation.

For Soviet ideology, national issues were the worst, since internationalism was the cornerstone of the USSR.

And when it became impossible to ignore developments in Armenia and Artsakh, Russian newspapers began to label rally participants and supporters of Nagorno-Karabakh’s self-determination as “nationalists” and “extremists”.

The main print organ of the USSR, Pravda (“Truth”) in its March 21 issue wrote that the rallies were well organized, and there were no casualties or destruction, which, according to the paper, proved that the Armenians “were getting tips from the other side of the ocean.”

The intervention of the West and active involvement of “some nationalist elements” became the view with which the central press characterized the movement.

Naturally, the overseer and outdated ideological nature of the press aroused anger in Armenia: joining the rallies were people who demanded that central newspapers reflect reality.

Created was a new situation where the press could no longer work as it used to. It had to change. People had already changed.

Nune Hakhverdyan