A few days ago, I returned to Yerevan from Tbilisi. When passing by the village of Kober in Armenia, my taxi driver told me how the last time he came this way with his family, much to his dismay, his school-age daughter asked him to stop the car so they could go into the village.

It turns out that a recent sentimental storyline in a popular Armenian soap opera took place in this village: an elderly male Kober resident supposedly found the main actress, who had been in a car accident, took care of her, and then the main actress found in this village not only her sweetheart, but also her twin sister, whom she never knew about. And so, the taxi driver’s daughter wanted to go into the village to find this Good Samaritan.

“Thank god that soap opera is over; we can have some reprieve,” said the driver, irritated by the inconvenience.

That in this information age, television is still for many a mysterious, magical box is clear. “It’s on television” and so it’s true — there are still people who believe this. Though they don’t trust news outlets, enchanted by a magical force, they often confuse what they see and hear on the (not only television) screen with reality.

And in this field of endless, enormous information, the Internet, powerful propaganda machines, and advertising at every step, this can be dangerous — especially for children.

After all, we make many of our daily decisions based on information from various media outlets: the more accurate and reliable that information, the more informed our actions will be.

On the other hand, an informed audience is a more fastidious audience, which impacts the quality of the media: and so, media literacy is also a way to reform the media industry.

Media Literacy Abroad

The rest of the world has long known about the dangers of the media: at the start of the previous century, French experts concluded that the best way to ward off the danger was to educate the audience from a young age. Today, the concept of media literacy is widespread in developed countries.

A media literate consumer is one who can critically comprehend the information provided by the media, understand the principles at work, is familiar with manipulation tricks, and is able to make good decisions in the media market. These skills are taught in many countries along with learning the alphabet.

Media literacy is taught in school in the UK, Canada, Australia, and the US. Basic rules of advertising and journalism are taught through games in primary school, while the senior grades conduct serious research, develop school programs, meet working media professionals, and critically discuss the field.

Another approach is to offer media education not as a single school subject, but as a topic embedded in all subjects; for example, discuss the language of media during language class, how history is reproduced and sometimes distorted in history class, the negative influence of the media (specifically, advertising) on food and lifestyle during phys ed or classes on healthy eating, and so on.

UNESCO emphasizes the importance of media literacy for school-age children: UNESCO’s Media Education: A Kit for Teachers, Students, Parents and Professionals is an amazing tool, which has also become the basis for developing media literacy classes in various countries.

Unfortunately, in post-Soviet countries, very little has been done in this area. In Russia, media literacy is taught by some higher educational institutions; a school program has also been developed; some experimental schools teach it, but it’s not a mandatory subject. In Ukraine, beginning in September of this year, media literacy will become a mandatory subject in school. For several years now, the subject has been taught in pedagogical institutions and tested in schools there. Ukraine’s press academy along with several NGOs developed a media literacy course for both the post-secondary education and school level: coming to an agreement with the Ministry of Education, they launched the school program, allocating time for media literacy classes in school — and basing its program on the UNESCO media education kit.

Unfortunately, in post-Soviet countries, very little has been done in this area. In Russia, media literacy is taught by some higher educational institutions; a school program has also been developed; some experimental schools teach it, but it’s not a mandatory subject. In Ukraine, beginning in September of this year, media literacy will become a mandatory subject in school. For several years now, the subject has been taught in pedagogical institutions and tested in schools there. Ukraine’s press academy along with several NGOs developed a media literacy course for both the post-secondary education and school level: coming to an agreement with the Ministry of Education, they launched the school program, allocating time for media literacy classes in school — and basing its program on the UNESCO media education kit.

Media Literacy in Armenia

Until recently, media education in Armenia was understood solely as computer literacy: that is, computer skills and Internet security. Such subjects are included in the school curriculum and various NGOs implement programs on this topic.

Armenian state documents and education reform programs attach great importance to teaching critical and analytical thinking skills and effective communication skills; however, independent thinking, analyzing current events, and developing the ability to understand and apply new technologies are emphasized in the National General Education Curriculum. But nearly nothing is done in the area of media education. There is a section on the work of news media only in the textbook for social studies class.

There are one or two schools (such as the Mkhitar Sebastatsi educational complex) that emphasize the importance of media’s role in education and actively incorporate media in the curriculum, but overall, the field is lacking.

Two years ago, Internews Media Support NGO began to work on a media literacy school program. The program was developed, a teacher’s handbook was produced, educational videos, articles on theory, and games were collected.

The program is for the senior grades and is comprised of 10 provisional classes including media history, the current situation, legislative and ethical regulations, economic activity and advertising, types of media and their unique characteristics, and skills to critically consume media goods.

The references and material included in the course allow teachers to deepen their knowledge and expand the scope of the 10 classes, modifying the extent and duration of the course.

The program was developed with experts from Armenia’s National Institute of Education, after which the Minister of Education and Science authorized Internews’ media education curriculum to be taught in schools: schools can choose to take this course and use the content as part of their current curricula or outside of it. The Ministry of Education and Science doesn’t yet intend to make media literacy a separate school subject, arguing that schools are overburdened.

Since last September, this program was tested in a few private and experimental schools; several groups of teachers were trained in Yerevan and in the regions; trained also were National Institute of Education employees who expressed a wish to apply the curriculum in their training courses and textbooks.

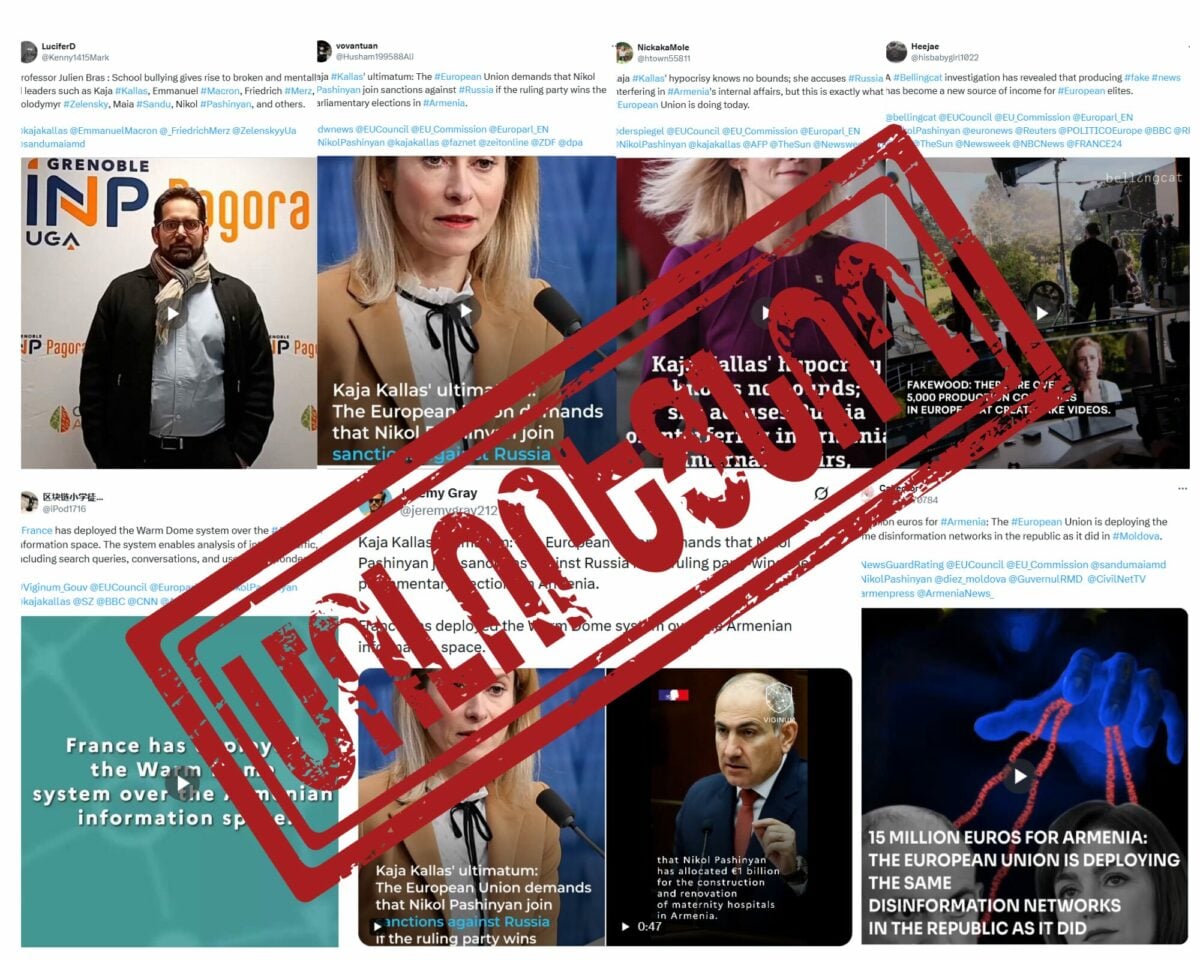

The course greatly interests children and teachers: penetrating the mysterious basket and understanding how it works is alluring. They began to see television differently, beginning to “doubt” and ask questions; that is, to critically take in the information.

To attract children more, a digital game was created, which will soon be made public and available to all. In the game, children can take a quiz, write the news, produce a radio program, gather TV programs, make a photo from a current event, and design the first page of a newspaper or a multimedia story with various components.

At the end of the game they find out how media literate they are; that is, to what extent they understand the work of the media, how much they can verify what they’ve seen on television, to differentiate between propaganda and journalism, to understand what aim a particular message has, and so on.

To put it broadly, a media literate child is a more conscious and informed citizen, who makes informed decisions and who can gather from flows of information that which she needs and which is useful.

If education is a weapon (as they often write on school walls), then media education can help protect us from the media’s negative influence.

The program prepared by Internews Media Support NGO and the digital game will be available to school principals and teachers in Armenia beginning this September; however, it will not be a mandatory part of the curriculum. As for which schools will find the time and wish to use them depends on the whim of school principals, the readiness of teachers, and, of course, the requirements of media literate children.

Lusine Grigoryan

Updated Sept. 11, 2013: The paragraph that begins with “Though in our state documents” was modified as it erroneously referred to skills taught in elementary and secondary school, when the author, in fact, was referring to skills taught in the National General Education Curriculum. Furthermore, the sentence “The program prepared by Internews Media Support NGO and the digital game will be part of school curriculum in Armenia beginning this September” was amended as it became evident that the program, in fact, will not be part of the school curriculum; however, teachers and principals may use it if they so wish.